UC Berkeley SSWANA Initiative Director Doaa Dorgham, second from left, discusses the importance of Arab American Heritage Month, and the road map to bringing about “big change.” (Photo courtesy of Doaa Dorgham)

As a Palestinian child growing up in Raleigh, North Carolina, Doaa Dorgham said she often felt isolated. Being the only Arab American student in her classes, she didn’t have a community to relate to, apart from her immediate family.

When talking about being Muslim and Palestinian, Dorgham said she’d get blank stares, and people often knew little to nothing about the identities she holds.

“I felt isolated,” said Dorgham, whose family immigrated to the U.S. from Kuwait City in 1990 to escape the Gulf War. “There was a lot of racism, microaggressions and implicit bias when it came to the way I was treated, but I didn’t really know how to articulate what I was experiencing,”

After 9/11, Dorgham said Islamophobia impacted the way she and her family were treated by others in her surrounding community. But in college, after organizing with American civil rights activists who worked alongside Martin Luther King Jr., Dorgham said she learned to use “love as resistance.”

Now, as director of UC Berkeley’s South Asian, Southwest Asian and North African (SSWANA) Initiative, Dorgham hopes to provide students, and the greater campus, with the resources and community that she didn’t have as a child.

In 2018, after student-led coalitions on campus pushed UC Berkeley to hire full-time staff who could build community among the campus’s SSWANA population, the initiative was created to support over 33 ethnic groups on campus that make up nearly 15% of the undergraduate student population.

Dorgham has led the initiative since its founding in 2019 and also teaches a seminar for SSWANA students through the program’s living learning community, a residential cohort that launched this year.

Berkeley News spoke with Dorgham recently about the importance of celebrating Arab American Heritage Month, and what the road map is to bringing about “big change.”

Berkeley News: The language around describing people who identify ethnically with areas and regions within the Middle East continues to evolve. How does using the acronym SSWANA help in that ongoing discourse?

Doaa Dorgham: When people that don’t know much about the region and its people go to watch a film like Aladdin, they don’t decipher between people from South Asia, Southwest Asia or North Africa. Those separate identities are just put all together as one. Those tropes of orientalism and Islamophobia are incorporated into their perspective not only in film, but in the unfair representation in the media.

Protesters gathered in downtown Minneapolis to denounce a 2017 executive order blocking citizens of some Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States. (Flickr photo by Fibonacci Blue)

And in a post- 9/11 world, we continue to see the impacts of Islamophobia on populations in the U.S. that aren’t even Muslim. Orientalism, which is this concept of how the West describes the East as being savage, exotic and/or many of the other tropes that are used are also generalizations that still exist.

SWANA is a decolonial term for the South West Asian/North African (SWANA) region in place of Middle Eastern, Near Eastern, the Arab World or Islamic World that have colonial, Eurocentric and Orientalist origins and are created to conflate, contain and dehumanize our people.

And so, the term SWANA was created to more accurately describe the region and people that identify with it that no longer politicizes them. It is also more encompassing of where countries are located geographically, and less so of how the West determined what the Middle East is.

On campus, we use the term South Asian, Southwest Asian, and North African (SSWANA). Both acronyms represent communities with shared experiences of racialization and othering across the country.

What are some issues that students within these communities are battling that the greater campus might not know about?

This is a community that has been invisiblized for so long, both in academic research and in resources that are being provided for them.

A lot of South Asian students have felt like there wasn’t really representation or spaces that highlight their experiences. And then, within Southwest Asian and North African communities, they’re racially categorized as white in the U.S. However, through the research we have found on campus, their experiences more closely mirror that of underrepresented groups, as opposed to their white counterparts.

The Turkish Student Association held a vigil at Sather Gate for victims of the 7.8 magnitude earthquake that hit Turkey and Syria on Feb. 6, 2023. (Photo by Liana Dagdevirenel)

It took a student-led effort in 2016 to advocate for the state to collect SSWANA data on UC applications. And that was the first time we actually had data to really showcase what the issues were in the community and to really think about how we move forward.

Berkeley’s 2019 campus climate report was also the first time SSWANA communities were included as separate categories. So, we were able to really find data that supported what we’ve known for so long — that SSWANA students are not receiving the tailored resources they need, and that many of them are suffering socio-economic hardships in relation to housing, mental health and food insecurity.

Many of these students continue to face microaggressions and hostile environments on campus.

How has the SSWANA Initiative helped to support students facing these issues?

When I first started my role, I did over 50 informational interviews with student organizations to really think about how we wanted this initiative to be there to address their needs.

Creating opportunities for students to engage within the community was very important to them, as is getting students acquainted with the appropriate resources and mental health support systems they need on campus.

“(Berkeley) students are so amazing,” said Dorgham. “… And to see how they grow from their first year onwards and seeing how they’re influencing and changing and cultivating communities within Berkeley and beyond is the most rewarding thing that I could have ever asked for.” (Photo courtesy of Doaa Dorgham)

Now I serve as a liaison for making students aware of those resources and understanding the complexities of being first-generation and navigating the campus for the first time. Our office also wrote grants to help support students by providing more counselors that can understand the nuances of SSWANA student identities.

The other important piece students expressed was having more political education and having the SSWANA Initiative serve as an office that can help uplift the narratives of students.

To utilize education as a form of empowerment.

We recently launched our SSWANA Living Learning Community Pilot this year. It’s a theme program that provides students with a yearlong seminar and cultural experience to get them acquainted with campus, all the while building a residential community together.

I teach the seminar through the initiative, and it focuses on both the historical and contemporary issues the SSWANA community faces. This first semester, we delved into the impacts of colonialism, imperialism and colonization within this one region. In the second semester, we are focusing on modern day liberatory movements and the importance of storytelling in dismantling some of the tropes that exist.

Dorgham teaches a yearlong seminar and cultural experience to acquaint SSWANA students with campus. (Photo courtesy of Doaa Dorgham)

It’s really exciting to create and provide some of the history, language and understanding of the region that I personally never had when I was growing up as a young adult.

And it has been so amazing to see the students engage with those concepts and relate it to their own identities and families. I hope it gives them more confidence in sharing their own thoughts and opinions.

A skill they can incorporate at UC Berkeley and beyond.

There are various Arab countries encompassed within the SSWANA region. Why is it important to have Arab American Heritage month celebrated on campus?

Arab Americans are defined as 22 Arabic-speaking countries that have ancestral ties and are connected through this linguistic identity. And SSWANA, again, is this term that’s used to depoliticize the region.

But while not all countries in the SSWANA region are Arab, the most important thing to know is that they have overlapping experiences of racialization and othering in the U.S., and that is really the tie between them.

So, it’s important to really think about the many ways that Arab Americans have contributed to advancing society, and it’s an opportunity for folks to learn and celebrate that cultural heritage and to understand the experiences of those communities.

Subscribe to Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley.

The SSWANA community seems to be very nuanced and really encompasses a lot of different ethnicities and people from different regions. But why should people outside of that community care about the experiences and issues that SSWANA students face?

Well, I think the question should be: Why should anyone care about what someone else is going through?

And I think it’s really important to understand this concept of collective liberation because of the impact that underrepresented groups face — due to systemic inadequacies in our institutions that work to collectively bring us down. So, the only way to collectively move forward is by advocating for all of our community members at the same time.

What is a really important road map is to understand the Third World Liberation Front from the 1960s and how it really took the collaboration of all of these communities on campus to figure out a way to teach history through the lens of ethnic studies.

Even more broadly, we can pull from the civil rights movement to help uplift the concept of social justice. Big change requires multiple entities coming together to create that change.

And I think that’s really the blueprint we are pulling from.

Charles Brown, Ysidro Macias, LaNada War Jack and Stan Kadani walk down Bancroft Way during a Third World Liberation Front strike march in 1969. (Photo courtesy UC Berkeley Ethnic Studies Library)

What can we do more to prioritize the SSWANA community?

I think the first thing is just to hear and engage with our communities and come to spaces we create for each other. That’s really the first step in broadening your scope and learning about these communities — attending events and understanding how folks can show up for one another.

On April 17, we are hosting the first-ever SSWANA reader panel , and it’s in partnership with the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, the Department of Ethnic Studies and the Asian American Research Center. And that is a really interesting panel that’s going to be held. They basically created the first interdisciplinary reader that really looks at Arab American studies and the nuances and impacts of that region.

I think that is a really good starting point for people to learn more about the community with some amazing academic researchers and community organizers that have really played a role in establishing this foundational amount of work in research.

When we talk about how to model collaboration, it can be seen in all these departments coming together to uplift the community.

What I would also say is: Listen to our students.

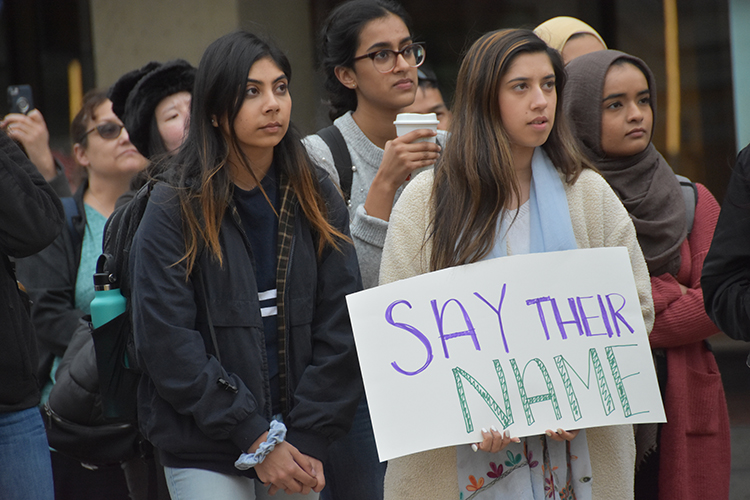

Berkeley students protested the March 15, 2019 mass shootings of two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand that killed over 50 people. (UC Berkeley photo by Hulda Nelson)

I truly love my job, and I think a big reason is because the students are so amazing. And to be a part of their journey and to see how they grow from their first year onwards and seeing how they’re influencing and changing and cultivating communities within Berkeley and beyond is the most rewarding thing that I could have ever asked for.

It’s such a privilege to work alongside these students. They’re nothing short of spectacular. And I hope they know that they always have someone advocating for them on campus.