North Korea’s official propaganda promotes idea of racial purity and moral superiority, scholar says

The Democratic People's Republic of Korea is not the last bastion of Marxist Leninism or of Confucian patriarchy, says visiting scholar Brian Meyers. Instead, it is guided by a paranoid ideology of race-based nationalism, holding that the Korean people are inherently purer than all others.

February 19, 2010

North Korean propaganda is rife with left-wing-sounding terminology such as “the masses” and “revolution.” But don’t be misled by the official rhetoric or the nation’s branding as a socialist republic, says scholar Brian Myers. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) is not the last bastion of Marxist Leninism or of Confucian patriarchy, as it is often characterized. Rather, it’s guided by a paranoid ideology of race-based nationalism, he says, holding that the Korean people are inherently purer than all others.

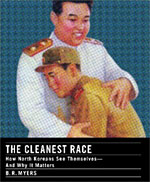

The Cleanest Race explores North Korea's official ideology.

The North Korea observer, who spoke last week at the campus’s Institute of East Asian Studies (IEAS), believes that Western misperceptions of the DPRK involve a failure to appreciate this ideology and its hold on the North Korean populace. Though “one of the most repressive nations on Earth,” he said, the Pyongyang regime enjoys considerable public support. There’s no way to understand that seeming contradiction, he suggested, “without going to the heart of what it tells its own people.”

Myers argued — as he does in his recently published book, The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves and Why It Matters (Melville House, 2010) — that the nation’s race-based ideology has its roots in Japanese fascism. Koreans historically considered themselves to be in the Chinese sphere of influence, he said. But in the early 20th century the Japanese annexed Korea and launched a campaign to persuade the peninsula’s people that they were of the same pure racial stock as the Japanese themselves, said Myers.

Then, when Japan left Korea at the end of WWII, pro-Japanese collaborators Koreanized the notion of a pure blood line, promoting pride in a morally superior Korean race. “Koreans are homogenous, therefore they are filled with brotherly love,” Supreme Leader Kim Jong-il is quoted as saying. On recently minted Korean currency, Myers noted, the faces depicted “could be clones.”

On the new North Korean 50 won note, the faces "could be clones," says scholar Brian Myers.

In failing to understand the mindset of the North Korean regime, Myers said, the West also miscalculates its foreign-policy options. In the United Nations and Washington, many believe that North Korean nuclear ambitions can be curbed through six-party talks involving the two Koreas, the U.S., China, Japan, and Russia. But what that attempt at engagement is doing, he believes, “is giving North Korea time until they can pursue a more consistently adventurous foreign policy.”

North Korean military aggression need not necessarily involve nuclear weapons, Myers noted. If the regime in Pyongyang wanted “a spectacular military victory” to legitimize its rule and rally national support, it might opt to attack a U.S. facility in South Korea, rather than fellow Koreans there, he said. By continuing to maintain dozens of U.S. military bases in South Korea, “we are playing right into Kim Jong-il’s hands,” asserted Myers. “If you wanted to undermine that regime, you would pull the American ground troops out.”

Myers teaches literature at South Korea’s Dongseo University and contributes commentary to The Atlantic Monthly and other national publications. His talk was part of the IEAS series “New Perspectives on Asia.”