Black Nature event explores environment for African American voices

Think of American nature writers, and African American authors probably don’t spring to mind. But the University of California, Berkeley, is hosting a March 4-5 symposium of leading poets and scholars who will explore 400 rich years of African American nature writing, as evidenced in a new, first-ever anthology of nature poetry by black writers.

February 23, 2010

Think of American nature writers, and African American authors probably don’t spring to mind. But the University of California, Berkeley, is hosting a March 4-5 symposium of leading poets and scholars who will explore 400 rich years of African American nature writing, as evidenced in a new, first-ever anthology of nature poetry by black writers.

Black Nature anthology

The anthology “Black Nature: Four Centures of African American Nature Poetry” features 180 poems by 93 African American poets ranging from early American colonist and slave Phillis Wheatley, who earned her freedom by her writings, to Pulitzer Prize-winner and professor Natasha Tretheway, California poet laureate emeritus Al Young, the late Gwendolyn Brooks – the first African American poet to win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry (whose papers are at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library), and Cecil Giscombe, a UC Berkeley professor of English and an African American poet known for exploring how place and the outdoors affect human inner lives.

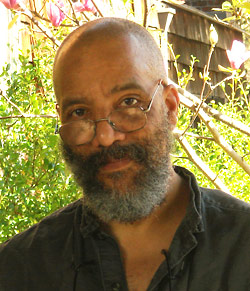

“Nature is everywhere in writing, yet public presentations of writing about nature tend to cast it as something that white writers do,” said Giscombe, whose book of poetry, “Prairie Style,” won the 2008 American Book Award by the Before Columbus Foundation.

In fact, when he Googled “black nature writing” and “African American nature writing,” the searches returned nine and four hits, respectively.

While African American writers are well known for offerings on politics, music and religion, their nature-related contributions are plentiful and little recognized.

Giscombe admitted that the genre of nature writing tends to make him uneasy because of what he sees as its tendency toward nostalgia, clichés and yearnings for simpler times. ”Having a more complicated view of things is necessary,” he said. “Inflecting the natural world while reflecting about life is complicated. Our identities are not discreet. They spill over, they trespass, they contradict. Our job as writers is to investigate the complexities of the world.”

Through public poetry readings, a panel discussion and accompanying conversations, UC Berkeley symposium organizers aim to correct the misperception that black writers don’t contribute to literature about nature, while exploring relationships between black writers and nature and looking at the environment through the lens of the humanities.

Camille Dungy, an associate professor of creative writing at San Francisco State University who edited “Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry,“ published in late 2009, attributes some of the disconnect between blacks and nature writing to the movement of large numbers of African Americans from the rural South to urban centers during the first part of the 20th century and the connections they were denied with the land. She divides the anthology into 10 sections based on recurring concerns, including open spaces; alienation from the land; power negotiations between humans, insects and other creatures sharing nature, history, devastation, positive transformation and more.

Poet Cecil Giscombe, professor of English

Carolyn Finney, an assistant professor of geography in UC Berkeley’s Department of Environmental Science, Policy & Management, will participate in a symposium panel, discussing a book she’s writing about African Americans’ links to the environment and to the environmental movement. Her book, “Black Faces, White Spaces: African Americans and the Great Outdoors,” contrasts African American history and experience with the dominant narrative, which Finney said is largely based on privilege and the personal visions of John Muir, David Brower and other white icons of the environmental movement.

“We haven’t all had the same choices,” Finney said, noting that slavery and Jim Crow laws regulated African Americans’ physical access, mobility and choice, leaving their marks on African Americans’ memory and how they map out their natural world. Still, other Americans, such as Native Americans, Asian and Latino immigrants, have unique perspectives on the environment that also are missing from the mainstream, she said.

“Those divisions may have served us for a while, but are they serving us now?” Finney asked.

Giscombe said there have been black nature writers who have gone unnoticed, and many more have been dissuaded by mainstream nature writing and an unwritten rule that blacks don’t write about the outdoors. It happened to him.

Almost 20 years ago, he was listening to African American writer Eddy Harris on the radio discussing his first-person book, “Mississippi Solo,” about canoeing from St. Louis to New Orleans. “It was weird,” Giscombe said. “I was shocked at my own reaction. I was 40, a published poet and professor. And when I heard Eddy Harris on the radio, he gave me this ‘permission,’ of sorts.”

That permission, Giscombe said, led him to write “Into and Out of Dislocation,” a book of connected essays about back country traveling in Canada. The book is, in part, an account of his search for traces of his distant relative, the Jamaican miner/explorer John Robert Giscome, who flourished in 19th century British Columbia.

Finney suggested that the recent explosion of interest in the environment – from climate change to hybrid cars to solar energy – could be a catalyst for finding new ways to decipher the environment and strategize about its guardianship. She foresees increased attention to how to start new, more expansive conversations about the environment and develop new ties between the environment and diverse communities.

“Diversity programs must do more than simply invite people of different cultural backgrounds to the table,” Finney said. “They must be willing to let go of the assumption that their view of the environment is a universal one, and be ready to collaborate with people to create new ways of framing and thinking about the environment.”

Joining forces for the program is the Berkeley Institute of the Environment (BIE), UC Berkeley’s English Department and Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, and San Francisco State University.

BIE Executive Director Dan McGrath said the institute, which explored in recent years the role of artists in the issue of climate change with two campus symposiums, is examining the development of a special center dedicated to the environment and the humanities.

Natasha Tretheway will lead off the symposium as the featured guest at the campus’s monthly Lunch Poems program, at noon on Thursday, March 4.

Among the authors and scholars who will share their experiences and insights at the two-day symposium are:

- Robert Hass, a UC Berkeley professor of English and a Pulitzer-Prize-winning poet as well as a former U.S. poet laureate

- Al Young, a California poet laureate

- Trethewey, a professor of English at Emory University in Atlanta and 2007 Pulitzer Prize winner in poetry for “Native Guard”

- Harryette Mullen, a Guggenheim Fellowship winner and UCLA associate professor of English and African American studies

- Carl Phillips, a poet and professor of English and African American studies at Washington University in St. Louis

- Ed Roberson, a Northwestern University lecturer and poet

- Evie Shockley, an assistant professor of English at Rutgers University who abandoned an environmental law practice for a career as a poet and public intellectual

- Camille Dungy, an editor, poet and professor in the Creative Writing Department at San Francisco State University

- Cecil Giscombe of UC Berkeley

- Carolyn Finney of UC Berkeley

More details about the Black Nature symposium is online at: http://bie.berkeley.edu/blacknature.