Possible new class of supernovae puts calcium in your bones

UC Berkeley astronomers have discovered several examples of an unusual type of exploding star that may be a new class of supernovae spewing calcium into the galaxy, which eventually ends up in all of us.

May 19, 2010

In the past decade, robotic telescopes have turned astronomers’ attention to scads of strange exploding stars, one-offs that may or may not point to new and unusual physics.

But supernova (SN) 2005E, discovered five years ago by the University of California, Berkeley’s Katzman Automatic Imaging Telescope (KAIT), is one of eight known “calcium-rich supernovae” that seem to stand out as horses of a different color.

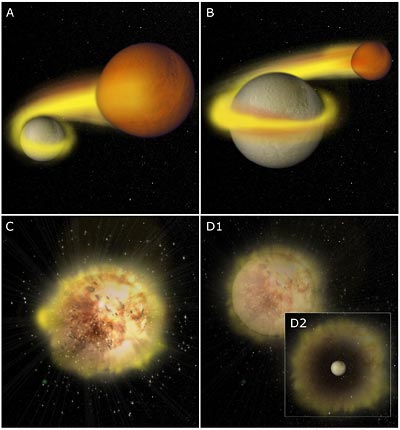

One theory of this new exploding system is that a white dwarf steals helium from a companion until the mass thief becomes very hot and dense and a nuclear explosion occurs. The helium is transformed into elements such as calcium and titanium, eventually producing the building blocks of life for future generations of stars. (Avishay Gal-Yam; Weizmann Institute of Science)

“With the sheer numbers of supernovae we’re detecting, we’re discovering weird ones that may represent different physical mechanisms compared with the two well-known types, or may just be variations on the standard themes,” said Alex Filippenko, KAIT director and UC Berkeley professor of astronomy. “But SN 2005E was a different kind of ‘bang.’ It and the other calcium-rich supernovae may be a true suborder, not just one of a kind.”

Filippenko is coauthor of a paper appearing in the May 20 issue of the journal Nature describing SN 2005E and arguing that it is distinct from the two main classes of supernovae: the Type Ia supernovae, thought to be old, white dwarf stars that accrete matter from a companion until they undergo a thermonuclear explosion that blows them apart entirely; and Type Ib/c or Type II supernovae, thought to be hot, massive and short-lived stars that explode and leave behind black holes or neutron stars.

The team of astronomers, led by Hagai Perets, now at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and Avishay Gal-Yam of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, presents evidence that the original star was a low-mass white dwarf stealing helium from a binary companion until the temperature and pressure ignited a thermonuclear explosion – a massive fusion bomb – that blew off at least the outer layers of the star and perhaps blew the entire star to smithereens.

The researchers calculate that about half of the mass thrown out was calcium, which means that a couple of such supernova every 100 years would be enough to produce the high abundance of calcium observed in galaxies like our own Milky Way, and the calcium present in all life on Earth.

Interestingly, a team of researchers from Hiroshima University in Japan argue in the same issue of Nature that SN 2005E’s original, or progenitor, star was massive — between 8 and 12 solar masses — and that it underwent a core-collapse similar to a Type II supernova.

“It’s a confusing, muddy situation now,” said Filippenko. “But we hope that, by finding more examples of this subclass and of other unusual supernovae and observing them in greater detail, we will find new variations on the theme and get a better understanding of the physics that’s actually going on.”

To make things even muddier, Filippenko and former UC Berkeley post-doctoral fellow Dovi Poznanski, currently at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and also coauthor on the Nature paper, reported last November another supernova, SN 2002bj, that they believe explodes by a similar mechanism: ignition of a helium layer on a white dwarf.

“SN 2002bj is arguably similar to SN 2005E, but has some clear observational differences as well,” Filippenko said. “It was likely a white dwarf accreting helium from a companion star, though the details of the explosion seem to have been different because the spectra and light curves differ.”

Astronomers have so far found only one example of this beast, however.

Filippenko and UC Berkeley research astronomer Weidong Li first reported an unusual calcium-rich supernova in 2003, and since then, KAIT has discovered several more, including SN 2005E on Jan. 13, 2005. Because these supernovae, like Type Ib, show evidence for helium in their spectra shortly after they explode, and because in the later stages they show strong calcium emission lines, the UC Berkeley astronomers were the first to refer to them as “calcium-rich Type Ib supernovae.”

It was SN 2005E, which went off about 110 million years ago in the spiral galaxy NGC 1032 in the constellation Cetus, that initially drew the attention of Perets, Gal-Yam and their colleagues. Using data provided by Filippenko and Li, as well as by the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, the Palomar Observatory in Los Angeles and the Liverpool Observatory in the United Kingdom (U.K.), they created a detailed picture of the explosion. The small amount of mass ejected in the explosion, estimated at 30 percent the mass of our sun, and the fact that the galaxy in which the explosion occurred was old with few hot, giant stars, led them to the conclusion that a low-mass white dwarf was involved.

In addition, the newly discovered supernova threw off unusually high levels of the elements calcium and radioactive titanium, which are the products of a nuclear reaction involving helium rather than the carbon and oxygen involved in Type Ia supernovae.

“We know that SN 2005E came from the explosion of an old, low-mass star because of its specific location in the outskirts of a galaxy devoid of recent star formation,” said Filippenko. “And the presence of so much calcium in the ejected gases tells us that helium must have exploded in a nuclear runaway.”

The paper’s authors note that, if these eight calcium-rich superonovae are the first examples of a common, new type of supernova, they could explain two puzzling observations: the abundance of calcium in galaxies and in life on Earth, and the concentration of positrons – the anti-matter counterpart of the electron – in the center of galaxies. The latter could be the result of the decay of radioactive titanium-44, produced abundantly in this type of supernova, to scandium-44 and a positron, prior to scandium’s decay to calcium-44. The most popular explanation for this positron presence is the decay of putative dark matter at the core of galaxies.

“Dark matter may or may not exist,” says Gal-Yam, “but these positrons are perhaps just as easily accounted for by the third type of supernova.”

Filippenko and Li hope that KAIT and other robotic telescopes scanning distant galaxies every night in search of new supernovae will turn up more examples of calcium-rich or even stranger supernovae.

“The research field of supernovae is exploding right now, if you’ll pardon the pun,” joked Filippenko. “Many supernovae with peculiar new properties have been found, pointing to a greater richness in the physical mechanisms by which nature chooses to explode stars.”

Other authors of the paper are UC Berkeley post-doctoral fellows S. Brad Cenko, Nevin N. Weinberg, Brian D. Metzger and Anthony L. Piro; UC Berkeley graduate student Mohan Ganeshalingam; Eliot Quataert, UC Berkeley professor of astronomy; Iair Arcavi and Michael Kiewe of the Weizmann Institute’s Faculty of Physics; Paolo Mazzali of the Max-Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Germany and the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy; David Arnett from the University of Arizona; and researchers from across the United States, Canada, Chile and the U.K.

The research of the UC Berkeley investigators was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, the Katzman Foundation, Gary and Cynthia Bengier, the Goldman Fund, and the TABASGO Foundation, with observational assistance from the University of California Lick Observatory and the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii.