Indian Country comes to Berkeley (and vice versa)

Berkeley faculty, staff and alumni — and participants from as far away as Alaska — collaborate on a four-day, first-of-its-kind Native American Museum Studies Institute designed to give Indians the tools to "tell their own stories, and to tell the stories from their perspective."

January 20, 2012

The Juaneño band of Mission Indians “has been in the process of federal recognition for 30 years,” laments Domingo Belardes, his voice hinting at the psychic and economic toll of a generation’s worth of government snubs. He dreams of expanding and improving his Orange County band’s modest, weekends-only museum as a way “to bring our people together through our culture.”

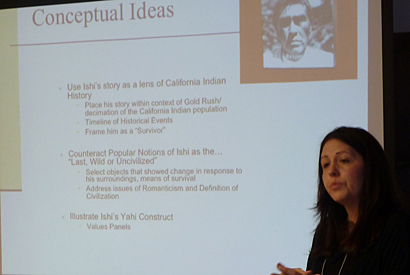

Nicole Lim describes the California Indian Museum's Ishi exhibit.

James Marquez, a White Mountain Apache and board director for MACT — a nonprofit providing services to Indians in Mariposa, Amador, Calaveras and Tuolomne counties — says his organization has both a building and a “pretty spectacular collection” of 250 Indian-made baskets and other cultural artifacts. Recognizing the enormous challenges and myriad details involved in developing, operating and curating a full-blown museum, however, he and his fellow board members are “trying to figure out whether to take the next step” into serious fundraising.

As UC Berkeley students streamed back to campus last week, Belardes and Marquez were taking part in a first-of-its kind Native American Museum Studies Institute, a collaborative effort of two campus entities — the Joseph A. Myers Center for Research on Native American Issues and the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology — and a third with strong campus ties, the California Indian Museum and Cultural Center in Santa Rosa. Over the course of four days, they and eight other participants got a crash course in everything from grantwriting and intellectual-property issues to curation, exhibit design and museum management. Tuition was free, though the institute’s 10 participants — Indians (mostly) and affiliated non-Indians from Northern and Southern California, Arizona, Montana and Alaska — were responsible for room and board.

Joe Myers

To Joe Myers, the Berkeley lecturer and law-school alum who heads the center bearing his name — and whose daughter, Berkeley grad Nicole Lim, is the director of the California Indian Museum — museums are a tool for Indians to reclaim their culture, their history and their very “Indian-ness.”

Before gaming came to Indian reservations, Myers says, they typically operated in what he calls “survival mode.” That may be changing, but casino money alone can’t reverse the impacts of brutal government campaigns of Indian removal and forced assimilation. “Even on those reservations where there’s been an economic boom because of gaming, we still have the poverty mentality,” Myers says. “We still have drug issues, alcoholism and lack of education and motivation to succeed.” The U.S. government’s decades-long program of sending Indian children away to boarding schools, he adds, “devastated cultural ties.”

Indigenous people’s museums, he believes, can help heal some of the damage. “What I think these museums will do — either on an individual basis, or on a collaborative, regional basis — is to let Indians tell their own stories, and to tell the stories from their perspective,” he explains. As with MACT, though, “even if you have the money for the building, you still have to have the skills to make it work — both for visitors who are not from the reservation and for those who are. You can’t just open the doors and expect it to succeed.”

The need to conserve and revitalize tribal cultural heritage, and give tribes a stronger voice in representing that heritage, was the beating heart of the institute. In addition to workshops on topics like collections management and cataloging — including a day at the Hearst’s basket and textile storage facility in Emeryville — participants were schooled in such issues as the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, better known as NAGPRA, the 1990 law that requires institutions receiving federal funding to return human remains and other cultural objects to tribes.

Under the leadership of Mari Lyn Salvador, the Hearst Museum — which has a large collection of bones dug up decades ago by Berkeley archaeologists — has hired additional staff to help with the challenging task of repatriating the bones of Native Americans to their respective tribes for burial. Myers, who co-conducted the NAGPRA workshop, says the Hearst “has turned the corner with Mari Lyn in getting artifacts back to tribes.”

Salvador, one of the many scholars and museum experts who took part in the institute, presented a brief but brightly illustrated history of her own education in “how to bring indigenous knowledge to museums,” beginning with lessons learned working with Kuna Indians in Panama while still in her 20s.

Lim, whose Santa Rosa museum is focused less on displaying artifacts than on using multimedia with the aim of “correcting misinformation” and “changing stereotypes” about Indians, recounted how she and her staff went about creating a permanent exhibit on Ishi, among the country’s best-known Indians — and its most misunderstood. She described grade-school classrooms in which Native American children, often a minority of one, are forced to “defend their history” against popular misconceptions.

“Our goal is that one day, our kids won’t have to do that,” Lim said.

On the institute’s final morning, the group sat in a circle in the Hearst galleries to hear Karen Biestman, who teaches at Berkeley Law and directs Stanford’s Native American Cultural Center, address the need to “transform ethnic museums into forums and places for confrontation, experimentation and debate,” all of it “grounded in the Native perspective.”

To Myers, who was instrumental in the creation of the California Indian Museum, that perspective is crucial — not just to museums, but to Indians themselves.

“We didn’t have our culture with us in the ways we should have,” says Myers, a Pomo who remembers riding the bus to Catholic catechism lessons as a boy in Ukiah. “Today we have young people thinking differently. They’re thinking it’s OK to be Indian, it’s OK to be proud of your people, where before — my mother’s generation especially — we’d bought into the idea that you had to get rid of that Indian-ness, that you wanted to be ‘an American.’

“But,” he adds, “you can be both.”

Related information:

- A century later, Ishi still has lessons to teach (NewsCenter article, September 2011)