One way to honor the Free Speech Movement’s 50th anniversary is to correct misconceptions about it. Visiting lecturer and New York University professor Robert Cohen — a UC Berkeley alumnus who received his Ph.D. in history here in 1987 — sets the record straight about several FSM myths. Cohen is the author of several books on Mario Savio, including Freedom’s Orator, this fall’s On the Same Page common text for incoming students.

Myth No. 1: The Free Speech Movement’s student organizers, led by Mario Savio, were troublemakers eager to disrupt the university.

Cohen: The FSM’s core organizers had no such intention. Veterans of the Bay Area and Southern civil rights movements, these students in fall 1964 planned to continue their campaign to end discriminatory hiring practices among Bay Area employers and secure voting rights for African Americans in Mississippi.

NYU professor Robert Cohen speaks at Berkeley about Free Speech Movement history. (UC Berkeley photo by Hulda Nelson)

When banned from doing this work on campus, they initially responded by meeting several times with Dean of Students Katherine Towle. Tactics escalated only when she made it clear the university wouldn’t budge. But even then, there was no planned takeover of any campus building.

The two sit-ins that followed, in Sproul Hall on Sept. 30 and on Sproul Plaza Oct. 1 and 2, erupted spontaneously and were non-violent. The first was a response by hundreds of students to not being cited for their proud defiance of the ban – only five students received citations. The second was after Jack Weinberg, one of the protesters staffing a political table on Sproul Plaza, was arrested. As he was put into a police car on the plaza, a crowd of students emerged and chanted “Take us all” and “Sit down,” sparking a 32-hour sit-in.

That sit-in ended peacefully – again contradicting the stereotype of UC Berkeley radicals as extremists – because Mario Savio and other protesters negotiated a pact with UC President Kerr that set up campus committees to examine free-speech rules and the disciplining of the protesters.

Savio supported the pact and, in his speech atop the police car, urged protesters also to accept the pact and disperse, which they did. During the month after the pact was negotiated, FSM leaders placed a moratorium on defiance of the ban. Only after negotiations broke down later that fall, over the administration’s insistence on retaining the power to discipline students for “illegal advocacy,” did the FSM activists again begin defying the rules.

As for Savio being the leader of the FSM: From the start, the leadership was collective; it was governed by democratically elected representatives. It had neither a maximum leader nor a president.

Savio became a media star because his oratory was so eloquent. He is remembered as a firebrand, but his speeches were more explanatory than incendiary. Savio didn’t hate the university, but was an idealist who wanted it governed more democratically. He loved learning and was a brilliant student, especially in science, and spent his last years, after getting bachelor’s and master’s degrees in physics, teaching at the university level.

Myth No. 2: Free speech was, as UC President Clark Kerr claimed, “a phony slogan,” since the UC allowed “full free speech” prior to the movement.

Cohen: UC Berkeley certainly did not have “full free speech” prior to the FSM. If there had been full free speech, the campus wouldn’t have restricted students’ political activity to an off-campus location.

These restrictions on free speech actually dated back to 1934 when, in response to the San Francisco General Strike and other radical insurgencies, the Bay Area and much of the West Coast fell into a Communist scare. Militant labor leaders such as Harry Bridges and others were denied the right to speak on campus, and no political speaker could appear without permission from the UC president or his aides. Students doing political advocacy were required to do so off campus. Before the late 1950s, this meant just outside of Sather Gate. Around 1958, it meant the brick-paved area just off the corner of Bancroft and Telegraph, on the campus side of the street.

Even Clark Kerr himself conceded, shortly after the Free Speech Movement, that, in 1964, “Our rules [barring political advocacy] were somewhat out of date.” By spring 1964, Stanford University had realized that such a ban was unconstitutional, and that it and the UC could, in Kerr’s words, “no longer draw the line” between speech and advocacy, and ban advocacy on campus.

Myth No. 3: The FSM wasn’t about liberty, but about hippies challenging decency with their speech, dress and drugs.

Cohen: This conflating of what was happening in Berkeley in 1964 with everything conservatives disliked about the mid-1960s (and, since then, with all that the right loathed about the late ‘60s) was first popularized by Ronald Reagan. When he ran and won the California gubernatorial election in 1966, he did so, in part, by pledging to “clean up the mess in Berkeley.”

One still hears echoes of this from the right. Just recently, a letter sent to the Wall Street Journal claimed that “Mr. Savio’s free-speech issue was his desire to lace his comments with the F-word whenever he felt moved.”

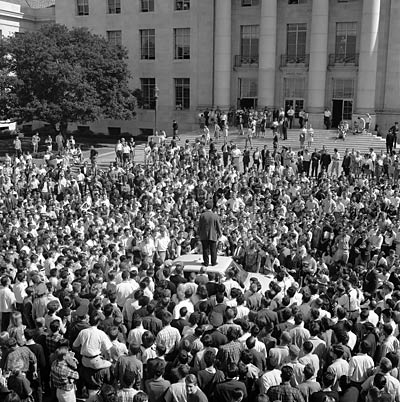

Mario Savio atop the police car holding FSM organizer Jack Weinberg, as students surround the vehicle in a spontaneous 32-hour sit-in.

Having just published a book of Mario Savio’s FSM speeches (The Essential Mario Savio: Speeches and Writings That Changed America), I assure you that none of Savio’s speeches contained the “F” word or any other obscenity. There was controversy over the use of indecent words at Berkeley, but it occurred in 1965, the semester after the FSM. While obscenity issues do have free speech implications — as when books such as Allen Ginsberg’s Howl was banned as offensive, or the comedian Lenny Bruce was arrested for obscene expression — the issue of obscene speech never came up and was not a focus of the FSM in fall 1964.

Note, too, that even when Savio in spring 1965 did discuss the controversy over the use of the “F” word, he would not even use that word, but instead the student euphemism for intercourse, “confront.” Savio, a former Catholic altar boy, never resorted to vulgarity in his political speeches.

While Reagan and his successors on the right may have scored political points by making the FSM a poster child for the counterculture, it is historically a serious mistake to compare UC Berkeley ’64 with Woodstock ’69. If you look at the iconic photo of the FSM marchers heading through Sather Gate en route to the Regents’ meeting in November 1964, the male students and faculty are formally attired in coats and ties, and the females in skirts. It’s a long way from coats and ties at Sather Gate to tie dye at Yasgur’s farm.

The issue in fall 1964 was free speech, along with the need for more democratic decision-making at the university and the right of students to advocate political causes — especially by continuing their work in the civil rights movement. Sex, drugs and rock and roll were simply not what the FSM controversy was all about.

The strip that sparked it all

Until the late 1950s, Sather Gate was a campus boundary, and since students only were allowed to do political advocacy work off campus, they set up their tables just outside the gate, on city property. Telegraph Avenue extended all the way to the gate at the time, and cars drove and parked where Sproul Plaza is today.

But as the university began to buy city property on both sides of that block of Telegraph, the campus border moved south to Bancroft Way. In the early ’60s, after Sproul Hall and the student union opened, the block closed, and the city deeded it to the campus. As a result, students’ tabling shifted to a 26-by-90-foot strip of sidewalk just off the corner of Bancroft and Telegraph.

In 1964, the campus discovered, following an inquiry from Oakland Tribune reporter Carl Irving, that most of the “Bancroft Strip” actually was campus property. (UC President Kerr had asked in September 1959 that it be transferred to the City of Berkeley, but it never happened).

The mostly brick walkway was 34 feet deep, of which the eight feet closest to Bancroft Way belonged to the city. As a result of this revelation, the dean of students, Katherine Towle, was ordered to send out a letter to students announcing that, effective Sept. 21, tables would no longer be permitted on the strip, and that advocacy literature and activities about off-campus political issues also would be prohibited there.

The rest is history.

Media coverage of the Free Speech Movement 50th Anniversary coverage available online.

Join the conversation on Twitter at http://bit.ly/TweetFSM50, #FSM50.