Low birth rates can actually pay off in the U.S. and other countries

As birth rates decline in countries that include parts of Europe and East Asia, threatening the economic slowdown associated with aging populations, a global study from UC Berkeley and the East-West Center in Hawaii suggests that in much of the world, it actually pays to have fewer children. The results challenge previous assumptions about population growth.

October 9, 2014

As birth rates decline in many countries that include parts of Europe and East Asia, threatening the economic slowdown associated with aging populations, a global study from UC Berkeley and the East-West Center in Hawaii suggests that in much of the world, it actually pays to have fewer children. The results challenge previous assumptions about population growth.

Researchers in 40 countries correlated birth rates with economic data and concluded that a moderately low birth rate – a little below two children per woman – can actually boost a country’s overall standard of living. While governments generally favor higher birth rates to maintain the workforce and tax base needed to fund pensions, health care and other benefits for the elderly, it is typically families that bear the brunt of the cost of having children, the study found.

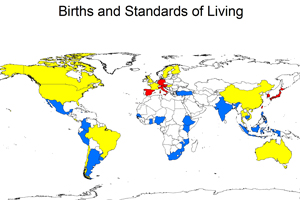

Yellow means birth rates are just right, blue, too high and red, too low (Graphics by East-West Center)

“Higher fertility imposes large costs on families because it is they, rather than governments, that bear most of the costs of raising children. Also, a growing labor force has to be provided with costly capital such as factories, office buildings, transportation and housing,” said UC Berkeley demographer Ronald Lee, an author of the far-reaching study to be published Oct. 10 in the journal, Science.

“Instead of trying to get people to have more children, governments should adjust their policies to accommodate inevitable population aging,” added Lee, who co-authored the report, “Is low fertility really a problem? Population aging, dependency, and consumption,” with Andrew Mason, an economist and senior fellow at the East-West Center.

Lee, Mason and fellow researchers compared government and private spending among all age groups using the National Transfer Accounts project, which studies how population changes impact economies across generations, and which they co-direct.

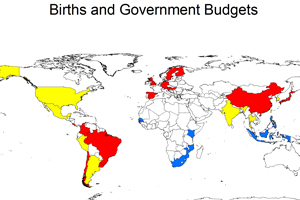

Red marks the regions where birth rates are too low

Their calculations were based on finding the birth rate and age distribution that would best balance the costs of raising children and of caring for the elderly. For example, they found that the U.S. birth rate is close to ideal for government budgetary needs, but that in parts of Europe and East Asia, average fertility rates are so low that they reduce living standards when public and private costs are included.

“A more complete accounting of the costs of children shows only a few countries in East Asia and Europe where the governments should encourage people to have more children,” said Mason, an economics professor at the University of Hawaii-Manoa. “In the United States and many other high- and middle-income countries, people are having about the number of kids that are best for overall standards of living.”