Drug perks up old muscles and aging brains

UC Berkeley researchers have discovered that a small-molecule drug simultaneously perks up old stem cells in the brains and muscles of mice, a finding that could lead to drug interventions for humans that would make aging tissues throughout the body act young again.

May 13, 2015

Whether you’re brainy, brawny or both, you may someday benefit from a drug found to rejuvenate aging brain and muscle tissue.

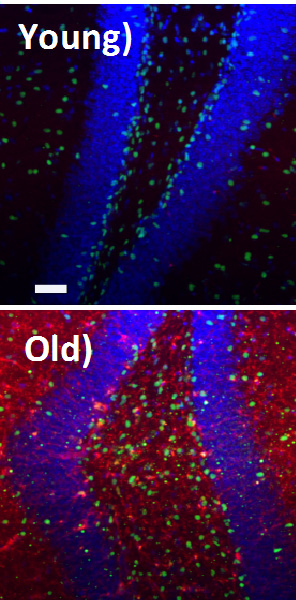

Images of cells in the brain’s hippocampus show that the growth factor TGF-beta1 (stained red) is barely present in young tissue but ubiquitous in old tissue, where it suppresses stem cell regeneration and contributes to aging.

Researchers at UC Berkeley have discovered that a small-molecule drug simultaneously perks up old stem cells in the brains and muscles of mice, a finding that could lead to drug interventions for humans that would make aging tissues throughout the body act young again.

“We established that you can use a single small molecule to rescue essential function in not only aged brain tissue but aged muscle,” said co-author David Schaffer, director of the Berkeley Stem Cell Center and a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering. “That is good news, because if every tissue had a different molecular mechanism for aging, we wouldn’t be able to have a single intervention that rescues the function of multiple tissues.”

The drug interferes with the activity of a growth factor, transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-beta1), that Schaffer’s UC Berkeley colleague Irina Conboy showed over the past 10 years depresses the ability of various types of stem cells to renew tissue.

“Based on our earlier papers, the TGF-beta1 pathway seemed to be one of the main culprits in multi-tissue aging,” said Conboy, an associate professor of bioengineering. “That one protein, when upregulated, ages multiple stem cells in distinct organs, such as the brain, pancreas, heart and muscle. This is really the first demonstration that we can find a drug that makes the key TGF-beta1 pathway, which is elevated by aging, behave younger, thereby rejuvenating multiple organ systems.”

The UC Berkeley team reported its results in the current issue of the journal Oncotarget. Conboy and Schaffer are members of a consortium of faculty who study aging within the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3).

Depressed stem cells lead to aging

Aging is ascribed, in part, to the failure of adult stem cells to generate replacements for damaged cells and thus repair the body’s tissues. Researchers have shown that this decreased stem cell activity is largely a result of inhibitory chemicals in the environment around the stem cell, some of them dumped there by the immune system as a result of chronic, low-level inflammation that is also a hallmark of aging.

In 2005, Conboy and her colleagues infused old mice with blood from young mice – a process called parabiosis – reinvigorating stem cells in the muscle, liver and brain/hippocampus and showing that the chemicals in young blood can actually rejuvenate the chemical environment of aging stem cells. Last year, doctors began a small trial to determine whether blood plasma from young people can help reverse brain damage in elderly Alzheimer’s patients.

Such therapies are impractical if not dangerous, however, so Conboy, Schaffer and others are trying to track down the specific chemicals that can be used safely and sustainably for maintaining the youthful environment for stem cells in many organs. One key chemical target for the multi-tissue rejuvenation is TGF-beta1, which tends to increase with age in all tissues of the body and which Conboy showed depresses stem cell activity when present at high levels.

Five years ago, Schaffer, who studies neural stem cells in the brain, teamed up with Conboy to look at TGF-beta1 activity in the hippocampus, an area of the brain important in memory and learning. Among the hallmarks of aging are a decline in learning, cognition and memory. In the new study, they showed that in old mice, the hippocampus has increased levels of TGF-beta1 similar to the levels in the bloodstream and other old tissue.

Using a viral vector that Schaffer developed for gene therapy, the team inserted genetic blockers into the brains of old mice to knock down TGF-beta1 activity, and found that hippocampal stem cells began to act more youthful, generating new nerve cells.

Drug makes old tissue cleverer

Microglia in the young brain (top) show little TGF-beta1,(green) as opposed to old brain (bottom).

The team then injected into the blood a chemical known to block the TGF-beta1 receptor and thus reduce the effect of TGF-beta1. This small molecule, an Alk5 kinase inhibitor already undergoing trials as an anticancer agent, successfully renewed stem cell function in both brain and muscle tissue of the same old animal, potentially making it stronger and more clever, Conboy said.

“The key TGF-beta1 regulatory pathway became reset to its young signaling levels, which also reduced tissue inflammation, hence promoting a more favorable environment for stem cell signaling,” she said. “You can simultaneously improve tissue repair and maintenance repair in completely different organs, muscle and brain.”

The researchers noted that this is only a first step toward a therapy, since other biochemical cues also regulate adult stem cell activity. Schaffer and Conboy’s research groups are now collaborating on a multi-pronged approach in which modulation of two key biochemical regulators might lead to safe restoration of stem cell responses in multiple aged and pathological tissues.

“The challenge ahead is to carefully retune the various signaling pathways in the stem cell environment, using a small number of chemicals, so that we end up recalibrating the environment to be youth-like,” Conboy said. “Dosage is going to be the key to rejuvenating the stem cell environment.”

Other co-authors of the paper are former graduate student Hanadie Yousef, now at Stanford University; and Michael Conboy, Adam Morgenthaler, Christina Schlesinger, Lukasz Bugaj, Preeti Paliwal and Christopher Greer of UC Berkeley’s bioengineering department and QB3.

The work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and a Rogers Family Foundation Bridging-the-Gap Award.

RELATED INFORMATION

- Systemic attenuation of the TGF-β pathway by a single drug simultaneously rejuvenates hippocampal neurogenesis and myogenesis in the same old mammal (Oncotarget)

- Bioengineers reprogram muscles to combat degeneration (2011)

- Scientists discover clues to what makes human muscle age (2009)

- Old muscle gets new pep in UC Berkeley stem cell study (2008)

- Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment (Nature 2005)