‘Rigging the election’ — rhetoric vs. reality

In recent weeks, Donald Trump has suggested that the electoral system is "rigged" or could be hacked to manipulate the outcome of this year’s campaign for the White House. But Betsy Cooper, executive director of the Center for Long-term Cybersecurity at UC Berkeley, says it’s highly unlikely a hacker could shift the victory from one candidate to the other. What we should really worry about, she warns, is a much bigger risk.

October 20, 2016

Just hours before Donald Trump made international news by refusing to say he would accept the results of the Nov. 8 election — an election he has repeatedly complained is “rigged” — one of his campaign surrogates sent a message about how, specifically, the outcome might be altered to steal a victory from the Republican nominee.

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has suggested the election is “rigged” against him. (Photo by Gage Skidmore via Flickr)

“Just off the top of my head,” Jeffrey Lord said on CNN, “now that a lot of us are doing electronic voting, just because I touch the button that says Donald Trump doesn’t mean it registered for Donald Trump.”

But Betsy Cooper, executive director of the Center for Long-term Cybersecurity at UC Berkeley, notes that the only hacks we know of in this year’s race have been hacks of the Democratic Party, as seen in an ongoing series of document dumps by Wikileaks. And she says it’s highly unlikely a hacker could reverse the will of the U.S. electorate.

Betsy Cooper is the executive director of Berkeley’s Center for Long-term Cybersecurity. (UC Berkeley photo by Anne Brice)

Despite an avalanche of disclosures clearly intended to damage Hillary Clinton’s White House bid, no one from her campaign has suggested the election results are not to be trusted, or that she might challenge them if she lost.

“On the Trump side, though, an overarching theme of his campaign has been that ‘the system is rigged,'” Cooper says. “I don’t think when he started that he was really referring to electoral systems. But it would be very easy to make an inference that’s really what he’s concerned about.”

Cooper, with more than a decade’s experience in homeland security consulting, doesn’t share that concern. What we should really worry about, she warns, is a much bigger risk.

The first thing to understand, she says, is the electoral system isn’t really a system. It’s a system of systems. Each state establishes its own processes for federal elections. “And that’s a good thing from a cybersecurity perspective,” says Cooper, “because what it means is you can’t hack the system as a whole.”

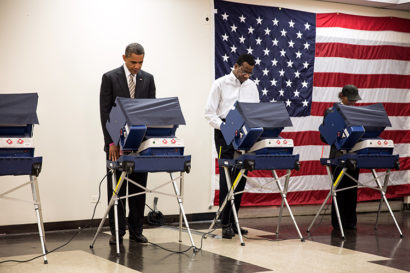

States use electronic or paper ballot systems or a combination of the two. (Official White House photo by Pete Souza via Flickr)

States decide what equipment to use — paper or electronic ballot systems or a combination of the two — and although some states use the same vendors as other states, she says it’s unlikely that someone could get into each individual system and change enough results to shift the outcome.

“You would almost have to have the perfect storm,” she says. “You’d have to have a single swing state affecting the outcome one way or another. You’d have to have that swing state be very close. And then you’d have to have evidence of some kind that that system may have been hacked. So to have all three of those things would be a pretty low-likelihood occurrence.”

She says the deeper risk is that the confidence in the system will be undermined whether or not a hack actually occurred.

“If there’s even a minute bit of evidence that a system was hacked or even a theory propounded that the system was hacked, that puts in a shred of doubt into whether or not the entire process as a whole was legitimate.”

Hackers have been in corporate systems watching and waiting for many years. (Photo by Thomas Hawk via Flickr)

And, she says, it’s very hard to prove a negative — that the system was not hacked — especially with recent corporate disclosures where hackers had been hiding in the underlying systems for three, four, sometimes five years.

“I think it would be very surprising to find evidence that a previous foreign government has actually affected the outcome or tried to affect the outcome of an election,” she says. “But I also wouldn’t be surprised to find that some hacker, foreign government or not, might have previously been in electoral systems watching and waiting much the way that a lot of these corporate vulnerabilities have been exploited.”

There are safeguards, she says, to keep electoral systems secure. States can put up walls in voting machines so they stay off the internet and provide less ability for interaction. Many states use paper backups to electronic ballots, which leave a paper trail for cross-referencing votes. And the desegregation of voting systems across states makes it much harder to manipulate the votes enough to change the outcome of the election.

But it’s not impossible, just highly improbable.

As we continue to rely more and more heavily on digital systems, she says, we will have to figure out how to maintain trust in our digital interactions. But Cooper isn’t worried about this election, even if Trump and his surrogates are — or at least claim to be.

“At the end of the day, I have confidence that our system will reach if not the optimal solution, a solution to allow our democracy to continue operating,” she says. “And that’s a great thing.”