Podcast: Growing up without free speech like ‘prison for your mind’

Parham Pourdavood, a UC Berkeley transfer student, grew up in Iran. He says he'd heard about government oppression, but hadn't seen it with his own eyes; he just knew he couldn’t speak his mind. It's why he's such a strong supporter of free speech today

November 21, 2017

Following is a written version of Fiat Vox podcast episode #20: “Growing up without free speech like ‘prison for your mind:'”

Parham Pourdavood was doodling in class one day when a classmate saw it and froze. “And my friend was like, ‘Did you know you could get killed for that.’” Pourdavood tore up the paper and hid the pieces in his backpack.

He lived in Tehran, Iran. It was 2005. The 10-year-old had drawn a funny cartoon from a famous photo he’d seen. It was of Ayatollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and its supreme leader, getting off of a plane, arriving in Iran in 1979 after leading the revolution from exile. Drawing cartoons seen as mocking government officials was against the law.

“The standard thinking is that these are all truths and no one can criticize them,” says Pourdavood. “You’re really afraid for your life.”

Parham Pourdavood, an incoming transfer student, came to the U.S. from Iran five years ago. (UC Berkeley photo by Anne Brice)

Pourdavood’s family came to the U.S. as refugees five years ago. Now, as an incoming spring transfer student in computer science at UC Berkeley, Pourdavood says he can’t imagine ever going back to Iran. Living in a country where you’re scared to express your opinion, he says, is like “prison for your mind.” It’s why he’s such a strong supporter of free speech, even speech that some see as harmful.

Growing up in Iran, Pourdavood says he, like most people, didn’t challenge the authorities. He wasn’t an activist. He studied hard in high school and didn’t draw attention to himself.

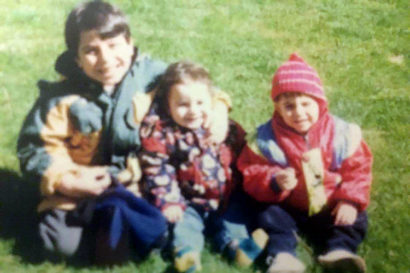

From left: Pourdavood at age 5 with his two younger brothers, Mahan, and Pedram, a sophomore at UC Berkeley studying computer science (Photo courtesy of Parham Pourdavood)

He had heard about government oppression — a girl protesting the 2009 reelection of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was killed in Pourdavood’s neighborhood; gay people were executed; women were arrested for improperly wearing their hijab — but he hadn’t seen it with his own eyes. He just knew he couldn’t speak his mind.

“I think it’s dangerous to silence people,” he says. “The first institution that’s going to take advantage of it is the government.”

Pourdavood has been following the debates on UC Berkeley’s campus and across the nation, on free speech, and whether hate speech can be silenced. Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ has dedicated the year to discussing the hotly contested topic in a series of panels, lectures and other events. “We’re going to have a free speech year at Berkeley,” she announced at a back-to-school press conference in fall 2017.

Some people, like Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky, say the First Amendment guarantees everyone’s right to freedom of expression, no matter how offensive. “The only way our speech can be protected tomorrow is to make sure we’re protecting the speech that we don’t like today,” said Chemerinsky at a panel discussion on free speech in September.

Other people, like john powell, a law professor and director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, say hate speech inflicts harm and shouldn’t be tolerated. “It doesn’t mean we should ban speech,” said powell, also on the free speech panel. “But it means the rationale, the underlying jurisprudence of speech, is radically incoherent.”

Free speech, says Pourdavood, is something that a society should protect. “If you don’t allow hate speech, free speech is going to be gone, too.”

The European Court of Human Rights sees it differently. It’s an international court that hears complaints of human rights violations from its 47 member countries. The court states that while “freedom of expression constitutes one of the essential foundations of a [democratic] society… it may be considered necessary in certain democratic societies to sanction or even prevent all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify hatred based on intolerance…”

So, according to the court, hate speech is a form of discrimination and shouldn’t be allowed.

Marc de Leeuw is a visiting fellow at UC Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Law and Society. (UC Berkeley photo by Anne Brice)

Marc de Leeuw is a visiting fellow at UC Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Law and Society. He says that verbally targeting a particular group of people based on their religion, ethnic background or nationality is taking away their freedom to live without fear, and excludes them from the “equality principle.”

“What certain people just see as a nice exchange of opinions, somebody else might feel is extremely harmful or a form of humiliation or discrimination,” he says. “The law has to clarify where we draw the line between freedom, hate and discrimination.”

De Leeuw, who grew up in the Netherlands, brings up a recent case that made headlines involving far-right Dutch politician Geert Wilders, who staged an anti-Moroccan chant on live television following his party’s victory in 2014 local elections.

Wilders was convicted in the Netherlands in 2016, charged with incitement and encouraging discrimination.

“And, of course, he then immediately victimized himself, saying he had freedom of speech,” says de Leeuw.

Young Dutch protestors hold signs that read: “Wilders is a racist; the PVV is a party of hate; Islamophobia is poison” and “For Hafid,” who is a Dutch-Moroccan writer who immigrated to the Netherlands when he was 7 years old. (Photo by Alex Proimos via Flickr)

In authoritarian countries like Russia or Iran, says de Leeuw, freedom of expression isn’t a right citizens have. But, he says in democratic societies, like the Netherlands or the U.S., citizens see governing institutions as a means of upholding their rights.

“We no longer think the state is the main opponent,” he says. “Now the state needs to guarantee our rights, and one of them is freedom of expression. But there are also rights that protect religious freedom, and against racism. We have all these other rights that need to be balanced.”

But Pourdavood says everyone should be free to express their opinions, no matter how immoral. “That’s how we grow. That’s how we learn. By listening to different beliefs that are opposed to our own.”

“I’ve seen freedom — how easily it’s taken away,” says Pourdavood.

Free speech, he says, is a right that everyone should cherish. “It’s more important for people to save it, not the government. People should hold it dear. It’s not a burden; it’s a privilege.”