Largest recorded underwater volcanic eruption sheds light on deep-sea events

Seafloor eruption in 2012 produced a huge raft of pumice in the southern Pacific

January 11, 2018

They knew it was big when satellite images showed that the pumice bobbing to the surface had created a floating raft covering 400 square kilometers, or more than 150 square miles.

The 2012 eruption of the Havre volcano took place three-quarters of a mile under the surface, on the ocean floor 600 miles north northeast of the North Island of New Zealand, and offered researchers a rare opportunity to study submarine eruptions. About 80 percent of Earth’s volcanoes are located on the seafloor, and volcanism is not only an important source of heat and chemicals to the ocean but supports unique forms of life.

“Underwater eruptions are fundamentally different than those on land. There is no on-land equivalent,” said Michael Manga, a UC Berkeley professor of earth and planetary sciences who is a co-author of a paper about the aftermath of the eruption published online today in the journal Science Advances.

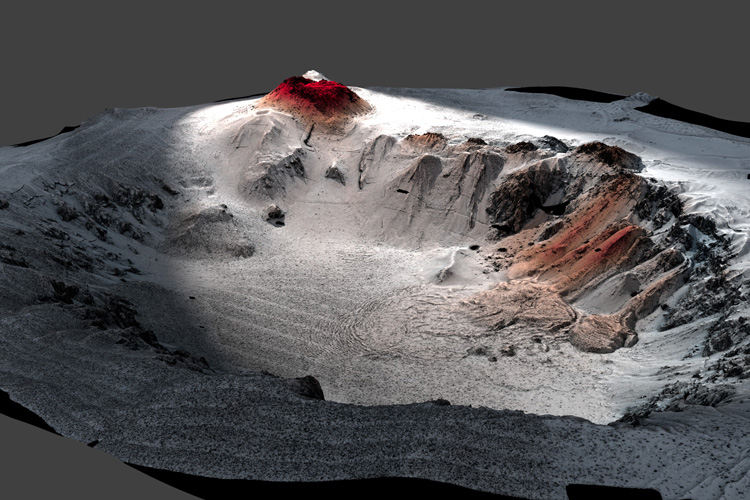

Using remotely operated and automated submersibles, Manga and an international team led by University of Tasmania researchers mapped the underwater caldera and compared the seafloor in 2015 to earlier maps of the volcano obtained after its discovery in 2002.

Using remotely operated and automated submersibles, Manga and an international team led by University of Tasmania researchers mapped the underwater caldera and compared the seafloor in 2015 to earlier maps of the volcano obtained after its discovery in 2002.

“Having the pre-eruption map of Havre volcano allowed us to know exactly what and where the new eruption products were on the submarine edifice,” said lead author Rebecca Carey, a volcanologist at the University of Tasmania in Hobart, Australia. “This event is a scientific gold mine, as for the first time there are quantitative constraints on submarine eruption dynamics and the role of the ocean in modulating those dynamics.”

They found that the eruption was very complex, involving more than 14 aligned vents that represent a massive rupture of the volcano. Some 80 percent of the volume of the pumice ended up in the floating raft and was dispersed throughout the Pacific Ocean, landing on Micronesian island beaches as well as the East Australian seaboard.

“The eruption blanketed the volcano with ash and pumice and devastated the biological communities. Biologists are very interested to learn more about how species recolonize, and where those new species are coming from,” Carey said.

The findings will help scientists like Manga and Carey understand older undersea eruptions and also prospects for mining metals and minerals.

RELATED INFORMATION