Podcast: At Berkeley, nobody stuffs a bird like Carla Cicero

The staff curator of birds at UC Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology preps Lux — the peregrine falcon born on the Campanile that died last year after striking a window on campus — to become part of the museum's collection of 750,000 birds, amphibians, reptiles and mammals used for research

September 25, 2018

After Lux — one of the peregrine falcons born on the Campanile — died last year after striking a window of Evans Hall, the campus community was heartbroken. But Carla Cicero, the staff curator of birds at UC Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, has given the peregrine a new purpose. Lux is now one of 750,000 specimens — birds, amphibians, reptiles and mammals — at the museum used for research at Berkeley and across the world. Lux is the 4,287th specimen that Carla has prepped for the museum in the past 30 years. Although the museum is closed to the public, for one day a year — Cal Day, in April — people are invited in to see special displays.

Following is a written version of the podcast:

I’m in a lab in the basement of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at UC Berkeley. In one corner, a set of antlers soak in a tub of water. In another, beetles are snacking on a skull. When I look up, a giant wandering albatross stares back at me.

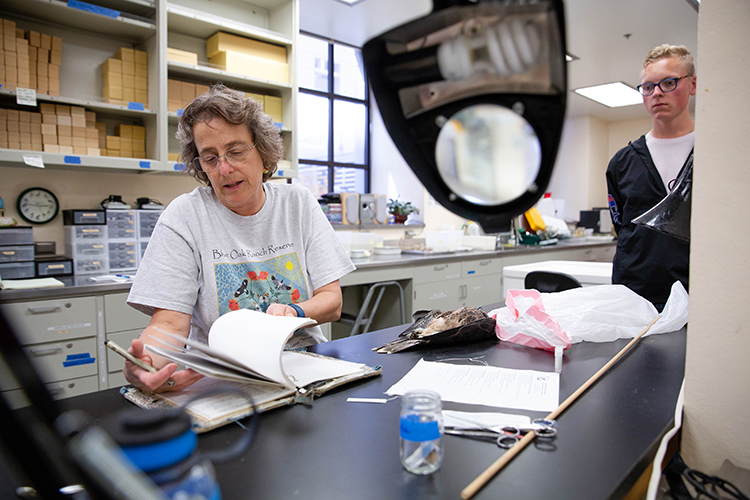

Carla Cicero is the staff curator of birds for the museum. She’s about to prepare a bird for its collection of about 750,000 amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. There are some 190,000 birds in the collection.

Today, she’s preparing a bird that many of us know as Lux — the peregrine falcon that was born on the Campanile last year and died after striking a window of Evans Hall. She records meticulous data about each specimen.

“This is my catalogue of stuff that I’ve prepared this year, a lot of which I’ve collected,” says Cicero. “I assign them my own number.”

“Is that 4,200…?” I ask.

“4,287, yeah. So, that means I’ve prepped 4,287 since I started, so it’s been about 30 years.”

Lux’s body is going to become a study skin — something that researchers at UC Berkeley and across the world can use in all kinds of research. Preparing a study skin takes a lot of patience and attention to detail.

“What I like about it is, it’s a mixture of science and art,” she says. “The science part is this part and taking the tissue and measurements, then the art part is actually making a nice-looking skin out of it.”

And you have to have a strong stomach. This is not a job for the squeamish. During the prep — which took about three hours — there was a lot of bone crunching.

The museum was founded in 1908, but the oldest specimen — a shorebird called a Red Knot collected in England — dates back to 1836. All of the specimens are listed in an online collections database called Arctos.

The museum acquires specimens in several ways. Students and other researchers collect them in the field. Wildlife rehab centers and zoos donate animals that have died. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sometimes confiscates animals at customs.

And one thing that surprised me is that the public drops off a lot of dead animals at the museum, too.

Cicero says it’s actually against the law to pick up a bird or its part — even a feather — without a permit. Every bird except rock pigeons, European starlings and house sparrows, which have all been introduced to the area.

“North American birds are protected by law by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act,” she says, “so anything we do, of course, we have to get permits to collect. We also have permits to salvage and accept things.”

But, she says, as long as you bring a dead bird to a museum, there’s a kind of unwritten good samaritan clause that makes it ok. But if you keep it for your own collection, you’re committing a felony.

“So now I’m going to turn the skin inside out,” says Cicero. “Now the fun begins. So basically, you just roll it like a sock, use the bill, there it goes.”

But Cicero isn’t done with the study skin yet. She still has to clean it, replace the brain, eyes and body with carefully rolled-up cotton, then put in a small wooden dowel to hold its shape. After that, she stitches it together and sets it out to dry.

After a few weeks, she’ll freeze it to make sure all the pests are dead, and then it’ll go into a drawer with the other peregrine falcons from the area as part of the collection. It’s a vast resource that Cicero hopes is around for as long as we are.

To learn more about the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, visit mvz.berkeley.edu.

If you want to donate a dead bird, bird eggs or a nest, amphibians, reptiles, mammals or related materials, see these guidelines.

To volunteer or work in the museum, see these employment and engagement opportunities.

Listen to a podcast about the Campanile’s peregrine falcons on Berkeley News.