Berkeley’s Julia Morgan collection shows alumna designed spaces for women

UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design Archives feature prestigious alumna’s hand-sketched drawings for women’s buildings

March 30, 2020

Sifting through the over 1,000 pieces of paper notes and hand-sketched drawings from the Julia Morgan collection at the Environmental Design Archives at UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design (CED), curator Chris Marino found an interesting trend.

“I knew she was a prolific architect,” said Marino. “But I didn’t realize that so many of her projects were buildings for women’s organizations.”

As the only woman in Berkeley’s Class of 1894 to graduate from the College of Engineering — the university’s architecture program was not established until 1902 — Morgan will be featured prominently on banners across campus this fall for the current yearlong celebration of influential and pioneering women who have studied, researched or worked at Berkeley. Women were first admitted to the campus 150 years ago.

One of the only images UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design Archive has of Morgan. The archive collection has more of a focus on the architect’s projects.

(Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design Archives)

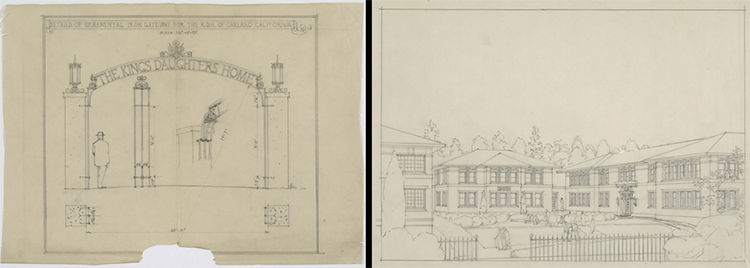

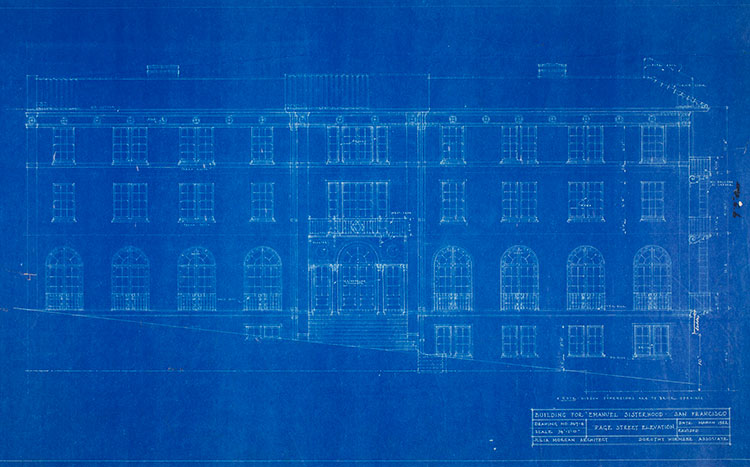

From the more than 700 commissions Morgan worked on, around 100 were designed and constructed specifically for women. The archives contain sketches and floor plans of buildings including the Emanuel Sisterhood Residence, now the San Francisco Zen Center; Phoebe Hearst Memorial Gymnasium, on the Berkeley campus; and El Campanil, the bell tower at Mills College in Oakland.

Marino, who has worked at the archives since 2014, said that Morgan’s work, preserved in a secure, climate-controlled vault, includes project drawings, historic photos and Morgan’s academic work.

The Environmental Design Archives is a non-profit research facility at CED that is committed to raising awareness of the architectural, landscape and design heritage of Northern California and beyond. It does so by collecting, preserving and providing access to primary records of the built and designed environment. Since 1959, community members, and Morgan’s colleagues and family members have donated to the archives’ Julia Morgan collection.

“The documents we steward provide a window into the past — unfiltered access to documents created by Morgan herself and physical proof of her prolific career, skills, incredible hand, design development, structural knowledge and how she was integral in designing spaces for women to advance in society,” said Marino.

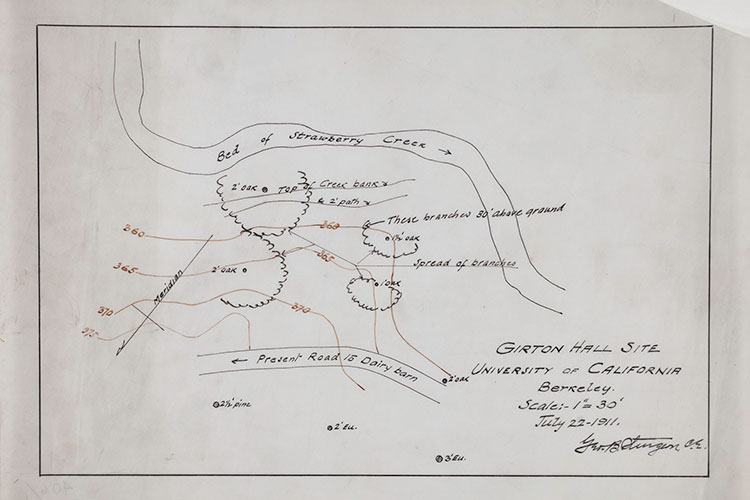

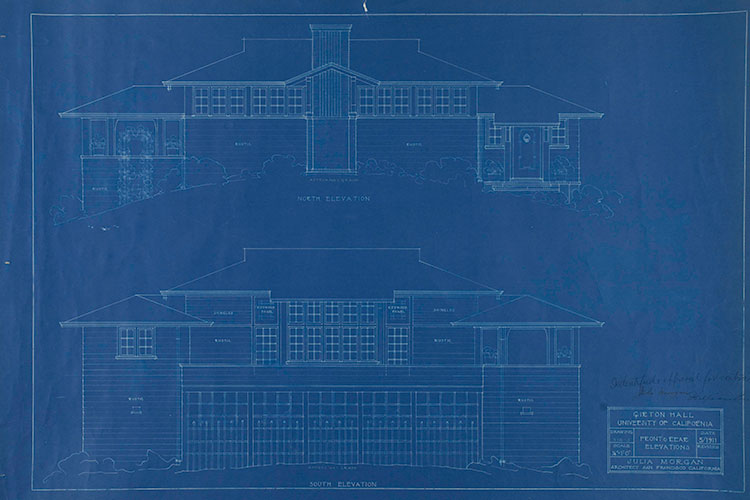

Morgan also designed Girton Hall, now known as Julia Morgan Hall, at the University of California Botanical Garden. The space was created in 1911 as a gathering place for female students who wanted a counterpart to Senior Hall, a meeting place for male students.

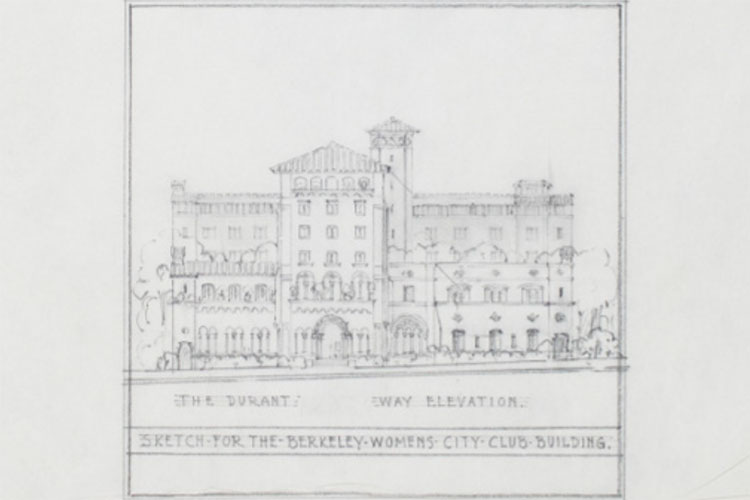

Marino said Morgan was commissioned by many women’s city clubs throughout the years, but the largest project was for the Berkeley Women’s City Club in 1929, which was completed in less than 11 months.

“Women’s clubs were really popular in the 1900s,” said Marino. “They were places where women got together and held classes on literature and economics. They also discussed civil engagement strategies and organized actions to impact the political climate.”

‘A woman doing unusual things’

Karen McNeill, who graduated from Berkeley’s Ph.D. program in history, has been a Morgan historian for over 20 years. She said Morgan was never an unabashed member of California’s women’s movement in the early 20th century.

But Morgan did navigate social networks of women who advocated for women’s rights throughout her academic years. Those relationships would influence the trajectory of her career, said McNeill.

Morgan grew up in Oakland, attending local public schools, and was one of 100 women who attended the University of California in 1890. She began studying civil engineering as a second-year student.

The Environmental Design Archives contains Morgan’s handwritten notes from these courses, and McNeill said Morgan was likely the only woman sitting in a room filled with men.

“She was aware she was a woman doing unusual things,” McNeill said.

Morgan was also a member of the university’s oldest sorority, Kappa Alpha Theta. She would go on to design the organization’s residence in 1908, and those sketches are in the campus collection.

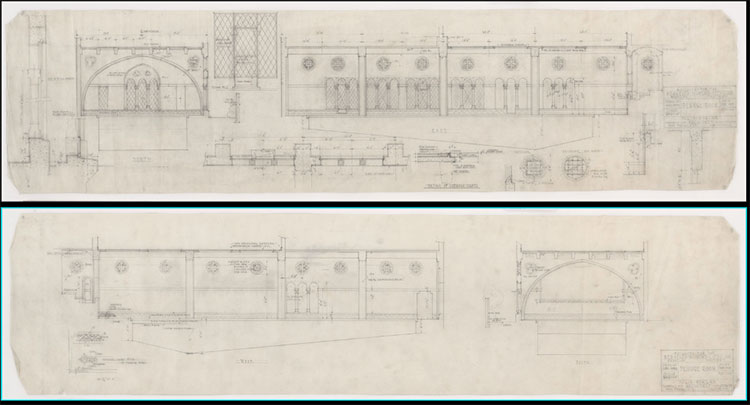

This drawing is a prime example of Morgan’s attention to detail, not only as a seasoned architect, but also as a student.

(Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design Archives)

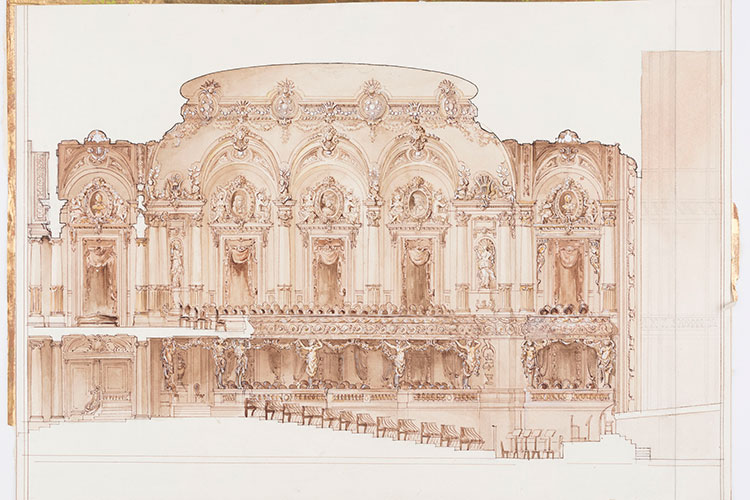

In 1896, with the encouragement of her Berkeley professor and mentor Bernard Maybeck, Morgan attended the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts (French National School of Fine Arts) architecture program in Paris. She was the first woman accepted, after being denied admission several times, due to her gender, and faced discrimination as the only woman in the program.

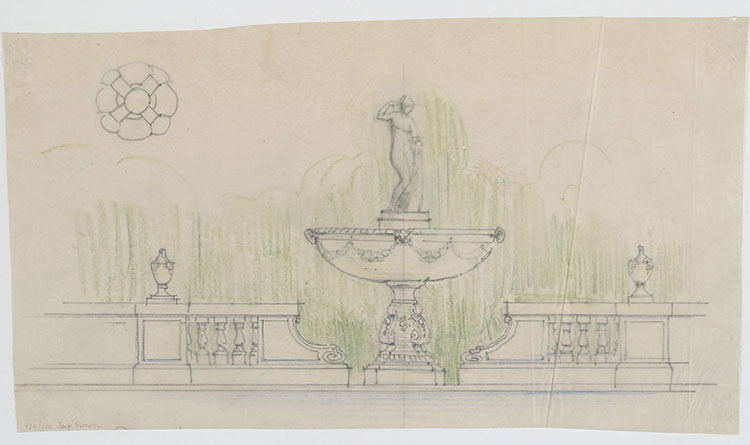

Still, Morgan excelled there. Marino pointed to Morgan’s student drawings in archives that include picturesque pillars and statues that she said reveal “an incredible sense of detail.”

While in Paris, Morgan was exposed to feminist views through Union des Femmes Peintres et Sculpteurs (the Union of Women’s Painters and Sculptors), an activist organization dedicated to the promotion of female artists, McNeill said. She also built relationships with philanthropist, feminist and suffragist Phoebe Hearst, UC’s first female regent, who later would secure Morgan to design projects in California and became an early patroness of her career.

“It was vital that Morgan had that spark in Paris, because she reacted by wanting to prove the male faculty and administration all wrong,” said McNeill. “It fundamentally affected her.”

After receiving a certificate in architecture from the program in 1902, Morgan moved back to California. She became popular with women from affluent backgrounds with the financial means to fund architectural projects for women.

She worked on UC projects with fellow architect John Galen Howard and then worked independently, becoming in 1904 the first licensed female architect in the state. What followed would be hundreds of commissions, including her first, the El Campanil bell tower at Mills College in Oakland, which was the first women’s college on the Pacific Coast.

Detailed sketches of the tower’s floor plan and design can be found in Berkeley’s archives, as well.

“She stepped into a time and period where she was used as a catalyst to manifest these buildings for women,” McNeill said.

‘Paving’ the way

As Morgan became a more established architect, not only throughout the state, but the entire country, she was recognized as a specialist in the use of reinforced concrete — a technology that proved beneficial for a building’s seismic performance.

Following the massive 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fires, Morgan was hired to oversee the remodeling of what is now called the Fairmont San Francisco, a hotel that had just been completed before the quake and then destroyed by fire.

As a woman in charge of the project, and with the press, wealthy male property owners and fellow architects ready to criticize her every move, Morgan was under immense pressure to do well, McNeill said. But despite organized labor issues and another fire at the site, Morgan managed a crew of 400 men and repaired the building in time for a grand reopening on the one-year anniversary of the disaster.

The bell tower at Mills College in Oakland was Morgan’s first commission as an independent architect. An initial sketch of the tower is pictured, left, alongside an archival photo of the final product, on the right.

(Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design Archives)

“To be that point person as a woman at that time, it seems hard to imagine,” said Margaret Crawford, an architecture professor at CED. “But she was straightforward. She was strong, but not aggressive. Her competence won the day, because she really knew what she was doing.”

Crawford teaches a California architecture course and gives her students a walking tour of buildings that Morgan designed, such as the former women’s gym on campus and the Berkeley Women’s City Club, on Durant Avenue, that is recognized as a California Historical Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Although Morgan was not a vocal member of women’s movements, Crawford said she was a trailblazer who created opportunities for women that she never had. For example, she said, Morgan hired women to work at her architecture firm on California Street in San Francisco, and that this was unusual for the time.

Morgan also had a big influence on Berkeley’s architecture program.

Morgan was a member of University of California’s oldest sorority, Kappa Alpha Theta. Here is a sketch she drew of the sorority’s residential house she would design in 1908.

(Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design Archives)

“It produced a lot of women architects who worked all over California,” said Crawford. “And like Morgan, these women architects hired other women architects. It created a very unusual kind of network, and a whole group of women architects, here on the West Coast.”

Crawford said although there currently are more female students in architecture programs than ever, the industry has a long way to go to increase the number of commissions that women receive in comparison to men.

Fourth-year architecture student and aspiring architect Sophia Conti said Morgan has been one of the only female architects recognized in history and has inspired her to help break barriers that still exist for women in architecture today.

“I definitely think the field of architecture is opening up to female architects, although there’s still a disparity,” said Conti. “But I’m just glad I live in a time that it is a possibility for me, and Julia Morgan kind of paved the way for that.”

UC Berkeley’s Environmental Design Archives can be viewed in person at Wurster Hall by appointment only, once the state’s shelter-in-place mandate has ended, and online through the Online Archive of California.