Campus archives reveal genesis of U.S. disability rights movement

The Disability Rights and Independent Living archives at the Bancroft Library document the powerful movement at Berkeley and across the U.S.

October 20, 2020

It was 1997, and Jane Rosario, a librarian at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, was on her way to visit Mark O’Brien, a former Berkeley student with an extensive literary collection of his own works. He was a poet and journalist and larger than life — and Rosario had the job of collecting his poems, essays and book reviews to include in the library’s archives on disability rights and the independent living movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

Mark O’Brien after he was admitted to UC Berkeley in 1978 at almost 30 years old. (Photo from the Disabled Students’ Program photograph collection, UARC PIC 2800H:152, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

“Mark was a major star,” said Rosario. “I was really intimidated by him.”

O’Brien, who became paralyzed from the neck down after contracting polio at age 6, was admitted to Berkeley in 1978 at almost 30 years old. His father, Walter, had fought for years for his son to be accepted to Berkeley after he read about the campus’s residential program for students with physical disabilities. Funded by the California Department of Rehabilitation, the program set each student up in a dorm room with a full-time attendant during the student’s first year — and footed the bill of $12,000. Although some scoffed at the cost, it was cheaper than living in a hospital, and it offered students something many of them hadn’t had before: a chance to live independently.

A crane after it lifted O’Brien’s iron lung through his dorm window in Davidson Hall in 1978. (Photo from the Disabled Students’ Program photograph collection, UARC PIC 2800H:153, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Rosario, who was a student at Berkeley at the same time as O’Brien, remembers when a crane lifted his iron lung — a 650-pound steel cylinder that he needed to breathe — through his dorm window, several stories above the ground. Although he spent much of his time lying in his iron lung, O’Brien was able to attend class in a specially designed wheelchair. He typed on his computer using a mouth stick that he clenched between his teeth to push the keys.

After he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English in 1982, O’Brien went on to publish his work in literary magazines and to advocate for disability rights. In 1990, he published Breathing, a collection of poetry that gave readers glimpses of his life — from the death of his sister to riding in his wheelchair on campus at night. That same year, he published an essay, “On Seeing a Sex Surrogate,” in Sun magazine; it was a deeply honest, first-person account of how he confronted his intense feelings of shame — of his physical self and his sexuality. It gained national recognition and went on to inspire the 1997 film, The Sessions.

“I really admired him and his writing,” said Rosario. “I was just so in awe of him, and I knew he could be pretty sharp, so I was scared to meet him. He was an intimidating person, with or without the iron lung.”

When she got to O’Brien’s home in Berkeley, Rosario thought it would be a one-time visit — she would muster the courage to sit and talk with him, then collect his poems and essays for the archives and move on to the next person. But it didn’t work out like that.

Susan O’Hara (left) was hired at Berkeley in 1975 as the coordinator of the Disabled Students’ Residence Program at Berkeley. (Photo from the Disabled Students’ Program photograph collection, UARC PIC 28H:208, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

“He would only give me about five poems every time I came to his house,” said Rosario. “He would have his assistant pull things, and he’d go over each and every one of them with me. It was incredible. It turned into a long, ongoing thing. I visited with him a lot.”

O’Brien’s literary works can be found at the Bancroft Library in the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement archives, a rich collection of personal papers, records from Bay Area disability organizations and transcribed oral histories of leaders, participants and observers of the movement that gained momentum alongside the civil rights and women’s movements in the 1960s and 1970s.

The archives, like all social movements in history, didn’t just happen — they took immense dedication and perseverance by activists on the campus to make them a reality.

It began with Susan O’Hara, who was hired in 1975 as the coordinator of the Disabled Students’ Residence Program at Berkeley. Under her leadership, students with disabilities were moved from a campus hospital, where they were previously housed, to residence halls on campus. In 1988, O’Hara was named director of the Disabled Students’ Program. The energy and activism around disability rights on campus and in the larger community was like nothing she’d seen — a movement that she believed deserved to be documented.

Ann Lage (left) was the manager of the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement archives project and Jane Rosario was the archivist. “It’s the best thing I’ve done in my professional life,” Rosario said of the project. (Photos courtesy of Ann Lage and Jane Rosario)

The director of the Regional Oral History Office, now the Oral History Center at the Bancroft Library, Willa Baum, agreed. But it was another decade before the center found funding for the project through a three-year federal grant from the National Institute of Disability Rehabilitation Research in the U.S. Department of Education.

By 1996, the archives project had officially begun. Rosario, the archivist for the project, worked alongside a small team of interviewers from the disability community who were hired by Ann Lage, assistant director of the Oral History Office who was managing the project. Interviewers included O’Hara, Mary Lou Breslin, Sharon Bonney, Denise Sherer Jacobson, Kathy Cowan, David Landes, Fred Pelka and Lage, who conducted a few post-grant interviews.

Don Lorence in 1980 (Photo from the Disabled Students’ Program photograph collection, UARC PIC 28H:144, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

“There’s a watchword in the disability community: Nothing about us without us,” said Lage. “Although Jane and I were part of the project, it was thought of, initiated and basically carried about by people with disabilities who came on board as oral history interviewers for the project. We couldn’t have done our jobs without them.”

After the grant cycle ended, the team won another grant to start a second phase of the project that expanded its scope to focus on key advocates and organizations at work in the rest of California, plus in New York, Boston, Washington, D.C., Texas and several other states during the 1960s through the 1990s.

After eight years, the team had interviewed more than 100 people whose oral histories reveal the genesis of a powerful movement in Berkeley and across the nation that won remarkable improvements for the disability community, including the Americans with Disabilities Act, a federal civil rights law passed in 1990 — 30 years ago this year — that mandates equal rights and opportunity for people with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation and all places open to the general public.

Herb Willsmore (left) and Ed Roberts attend a Cal football game in 1969. Both Willsmore and Roberts were interviewed for the archives project. (Photo from the Disabled Students’ Program photograph collection, UARC PIC 2800H:007, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Those interviewed include Ed Roberts, a trailblazer with severe disabilities, who, after he was admitted to Berkeley as a student in 1962, famously demanded he live on campus, opening the door to a wave of students with disabilities seeking the right to live independently among other students. Roberts went on to found in 1972 the Center for Independent Living , which became a model for similar centers across the country, and was appointed director of California’s Department of Rehabilitation in 1975 by then-Gov. Jerry Brown.

Other oral histories include that of Mary Lou Breslin, also an interviewer for the project, who co-founded in 1979 the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, a national law and policy center; Berkeley alumna Judy Heumann, former assistant director of the U.S. Department of Education and the star of a new documentary, Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution; and Fred Fay, an advocate in Boston and Washington who fought for accessible transportation and was instrumental in developing adaptive computer technology for people with disabilities.

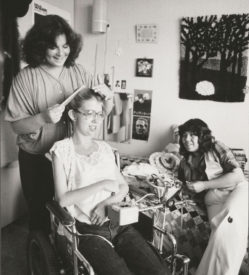

Students relax in the campus dorms in 1980. Once housed in Cowell Hospital, students with disabilities began moving to residence halls on campus after Susan O’Hara became the coordinator of the Disabled Students’ Residence Program in 1975. (Photo from the Disabled Students’ Program photograph collection, UARC PIC 28H:147, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

“In documenting a historical movement, there was this sense that we were breaking new ground the same way that the disability rights movement had done in Berkeley,” said Rosario. “And there we were, with the people who made that history. I just don’t think you get many chances like that, as an archivist or oral historian. It was just amazing. It’s the best thing I’ve done in my professional life.”

In 2000, the first phase of the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement archives documenting the movement on campus and in the Bay Area opened at the Bancroft Library. O’Hara, who retired from Berkeley in 1992, spoke with Berkeley News about the effort and how it would serve the public.

“This collection is going to enable historians and scholars to document the shift from a time when people with disabilities were seen as objects of charity needing medical supervision to people who were taking control of decisions affecting their own lives,” said O’Hara, who died in 2018 at age 80.

The complete collection of the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement archives that documents the movement in Berkeley and across the U.S. from the 1960s through the 1990s is available on the Bancroft Library’s website.

For an overview of the disability rights movement at Berkeley, read O’Hara’s article, “Fertile Ground: The Berkeley Campus and Disability Affairs,” published in 2009 in the Chronicle of the University of California.

Students pass under Sather Gate on the Berkeley campus in the 1970s. (Photo from the Disabled Students’ Program photograph collection, UARC PIC 28H:001, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)