COVID Stories: A professor and injured cyclist slows, mends, rides again

Before his accident in Wyoming, Harley Shaiken had taken 19 consecutive trips across the U.S.

March 11, 2021

Harley Shaiken has taken 19 consecutive trips on his bike across the U.S., from the West Coast to Chicago. Detroit, Minneapolis and Denver. Here, he’s on a trip through Grand Teton National Park. (Photo courtesy of Harley Shaiken)

The COVID-19 pandemic has separated us, but sharing stories about how members of the campus community have been surviving — and even thriving — since last spring can help draw us together. Berkeley News is gathering inspiring personal tales of heartache and triumph related to the coronavirus and will run them periodically in the coming weeks. If you’d like to pitch us your story, send a brief email to [email protected]. Check out the whole series here.

This is the seventh story in the series. It highlights Harley Shaiken, professor emeritus in the Graduate School of Education and the Department of Geography and director of the Center for Latin American Studies from 1998 to 2020.

I was still healing when the pandemic hit, and while there was much I would miss, I genuinely did not feel deprived by having to stay in one place. In part, I simply was glad to be largely in one piece after my accident, and while I needed a wheelchair, a walker, crutches and then a cane for months, I was thankful to be able to learn to walk again closer to home.

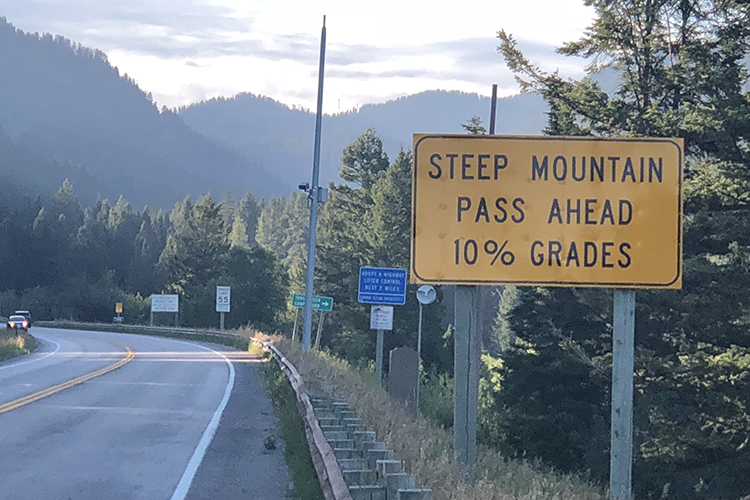

In August 2019, about a week into a bicycle trip through the Tetons, I had just climbed the 10,000-foot Togwotee Pass on a sun drenched morning thinking this is was bicycling at its best. As I began descending on a two-lane road, I unexpectedly entered a construction zone and was the last vehicle the flag person allowed to go through. But two pickup trucks came up behind me, unexpectedly. I was going fast downhill, fully loaded. I pulled into the closed lane, which had no equipment in it and was paved, and I was zipping along when, all of a sudden, the pavement completely ended in gravel and tar. I tried desperately to stop, but I crashed, flew over the bars, landed on my head and flipped over.

Harley Shaiken’s accident took place in Wyoming in August 2019 while on a solo cycling trip through the Teton Range of the Rocky Mountains. On that trip, he took a photo of signage at 8,000 feet on the Teton Pass climb while leaving Idaho for Wyoning. (Photo by Harley Shaiken)

When I came to, I was surrounded by concerned construction workers and a very capable young woman who was a deputy sheriff. They’d called an ambulance, but when it arrived, an emergency medical technician said it would take 90 minutes, at the least, to get to the hospital in Jackson Hole, and and then commented, “ … he might not make it; we need a bird.” So, they called a helicopter. As the accident was taking place, I initially thought this was it. I would later be told I’d shattered my pelvis in five places, had internal bleeding, torn muscles, a concussion, and external abrasions. I spent three days in the hospital in Jackson Hole. My daughter Mariela, who is a nurse practitioner at UCSF, flew to Salt Lake City and then drove all night to Jackson and was in my hospital room at 7 a.m. the morning after the accident and would stay with my while I was there.

“The pandemic was helpful, giving more time for Harley to heal. Plus, without the pandemic, he might have had the crazy idea of taking off heading east again!” said Beatriz Manz, Shaiken’s wife and professor emerita of geography and ethnic studies at Berkeley. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

I’m a seasoned and skilled cyclist. I’ve made 19 consecutive trips across the country from the West Coast to Chicago, Detroit, Minneapolis and Denver — self-contained and alone. I pack with many spare parts and tools and the ability to camp out. I don’t take ear buds: They’re a hazard on a bike, and there’s a music to the road, in the sound of wind in the trees, traffic, the forest, the elements. The sounds of birds are extraordinary; thunder in the distance a bit scary. And you encounter all kinds of animals—in fact, one sign that I saw the year before in the Rockies said “Bears on the road, stay in your vehicle,” which proved not particularly helpful on a bicycle. You wind up meeting local people in cafes and truck stops, and you talk with those just passing through like yourself. The year before, I had run into a half dozen tough-looking bearded riders on Harley-Davidson motorcycles at a gas station early one morning near Yellowstone. We started chatting, and one guy complained, “it’s outrageous that the president is defunding national parks. What about our kids?” Stereotypes melt away.

There’s a solitude and time to think and reflect on the bike and on these trips. I come up with ideas, thoughts, new approaches. In fact, I feel that it’s on a bicycle that I’ve developed some of my most creative ideas, which I scramble to write down at the end of the day.

Harley Shaiken took this selfie on Trail Ridge Road on his 2018 solo cycling trip through Rocky Mountain National Park. The highest point of the road is at an altitude of 12,183 feet. (Photo by Harley Shaiken)

And there is endless discovery when you least expect it. On one trip, I discovered a monument in a small town in central Kansas to Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, a Spanish conquistador who led 400 armed Spaniards and several hundred Indigenous allies searching for seven lost cities of gold in this area in 1541. On another trip, I had gone from Los Angeles to Chicago, retracing what was left of historic U.S. 66, which John Steinbeck termed the Mother Road in The Grapes of Wrath in 1939. In southern Illinois, the road went through the town of Mount Olive, and I discovered a miner’s cemetery in which Mother Jones, the legendary labor leader, was buried in 1930. Her tomb stands out with a towering 20-foot shaft flanked by statues of a miner and a worker on either side.

I try to stay in motels when possible and then camp when there are no motels. There were, really on about every trip, wildly unexpected things. Everything that can happen, does happen. On one trip, I arrived much later than expected — close to 11 p.m. in a tiny town — and there were no motel rooms available. With no real alternatives, I wound up spending the night sharing a room with a couple I had never met who had just rented the last room and had an extra bed. They did ask the motel clerk if I was a nice guy!

Harley Shaiken, in a wheelchair after his cycling accident in August 2019, gets a push from his daughter, Mariela, a nurse practitioner who flew to Colorado to be with him at the hospital. (Photo by Beatriz Manz)

On most of the trips, there were near disasters. I’ve experienced, close-up, tornados, two flash floods, torrential rain, hail in the mountains, hypothermia, and I ran out of water at the end of one long, hot day in the desert. I destroyed two tires on one trip and had 40 flats going from the West Coast to Chicago on another.

But I’ve only had one accident in those 19 trips. I’ve concluded that was more than enough!

I’m now pretty close to the level of fitness I had for that trip. I was able to avoid surgery, which I was thrilled with. The surgeons felt that because of the condition I was in, physically, from all this bicycling, and from the CT scans and X-rays they took— the worst fracture was a clean break, top to bottom, but in the same plane — that I would be able to heal without surgery.

I’m usually up at 4 a.m. and riding by 5. On a typical day, I might bike for 90 minutes to two hours and usually in very hilly terrains and fully loaded with bags, panniers, as that’s how I’ve become accustomed to ride from all the long trips. There is still a thrill when the sky begins to lighten and you first see the sun begin to rise.

I grew up in a working class household in Detroit; we’d never been out of the country, except for an occasional trip to Canada, which after all, was just south of the city, across the Detroit River. I grew up with California being the Promised Land and with the excitement of what it would be like to be on the road. My opening career — after a year and a half at the University of Chicago and then in the steel mills of Chicago — was as a machine repair machinist; I wasn’t thinking I’d become an academic. I served a four-year apprenticeship and worked as a machinist for about a decade. I was a good machinist, fascinated by what I did, but what I did in machine shops and on factory floors became central to what I would explore as an academic — studying work and unions, globalization, trade and, particularly, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and its successors.

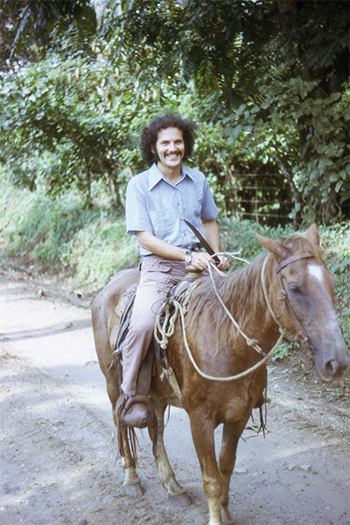

I decided at one point, in the early 1970s, as a journeyman machinist in my 20s, that I’d never been anywhere, and that I was going to Latin America. I didn’t speak Spanish, had never been to Latin America, and I didn’t know anybody, but it seemed like a promising idea, and the region intrigued me. I sold everything I had, said goodbye to the machine shop, got in my Corvette Stingray convertible, dark metallic green, and drove to California. I would find out many years later — at Berkeley, in fact — that Joan Didion would pose with that same model Corvette on the cover of her book The White Album. As I drove across country, I listened to Motown music — Diana Ross and I had been in the same high school class — and Bob Seger’s Detroit-inflected rock and, of course, Spanish language tapes so I could at least get from the airport in Mexico City 60 miles south to Cuernavaca, where I’d go to an intensive language school a friend in Detroit had recommended

Although a very different experience, the mystery — really, the poetry — of the road, the discovery of the West — laid the basis for my love of bicycling later.

When he was in his 20s, Harley Shakien discovered the allure of traveling and being out on the open road on trips to the western U.S. and to Central America. Here, he is in the Pacific lowlands of Guatemala. (Photo by Beatriz Manz)

I embraced and developed a lifelong passion for Mexico and its people, then went through Belizeinto Guatemala and into the highlands of Guatemala, all on local buses, with just a backpack, and promptly got lost. I landed in an obscure town in the highlands and met, unexpectedly, a young woman, Beatriz Manz, in the town square, who was a graduate student at the State University of New York and was running an anthropology field school. She was Chilean and getting her Ph.D. I fell in love and, as Bob Seger would later sing — ”I knew I was too far from home” — and we have been together ever since.

Bicycling came in after I met Beatriz, and we were both living in Detroit — she was teaching at Wayne State University, and I was working again in a machine shop and began bicycling from Detroit to Toronto.

I never ever had what you’d call a good bike. Over time, that became part of the appeal. You can spend $3,000 to $5,000 on a bike, or more. You can buy endless electronic equipment. My last bike trip, the one in 2019, was on a Novara Veritá, a REI-house brand bike that I bought used for $275. It did absolutely just great. It has an elegance and a simplicity and a durability of steel that I value.

The first thing I did, about 10 days after the accident, I knew would appear a little crazy. I taught “The Southern Border” course, with 300 students in Fall 2019. Beatriz originated the course, and later, we taught it together for over a decade. Why? I find teaching and interacting with students inspiring, and this course grapples with critical issues concerning the United States and Latin America. I felt deeply concerned — really angry — about U.S. government immigration policy, in general, and toward Central Americans, in particular, that was unfolding and felt it would be important to place these developments in context.

I felt it was an urgent and a historic moment. My body seemed to feel otherwise. Nonetheless, I taught from a wheelchair. I couldn’t even get out of bed by myself. I couldn’t walk. Beatriz and Mariela had to get me to class and back for the entire semester (neither got academic credit for sitting through much of the course). Chancellor Carol Christ was looking out for my best interests and wanted me to take medical leave that semester, but I decided I wanted to teach the course and felt I could do it and not compromise my teaching.

By the end of the semester, I could move with crutches. In spring semester, just before the pandemic, I was still in physical therapy, and I used either a cane or, at times, a walker.

I started bicycling again last June. The severity and unpredictability of the forest fires was deeply disturbing. I’ll never forget biking one morning when the sky was completely black and the sun a surreal red and orange because of the smoke. Over the last decade, climate change has been visceral on a bicycle — riding for days through smoke and, on occasion, seeing flames before fully understanding how dangerous and widespread all this had become. And let’s not forget a spike in extreme weather.

Harley Shaiken and Beatriz Manz look at a photo retrospective of Shaiken’s work at the Center for Latin American Studies and comments from colleagues, who surprised him with the gift. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Last September, we went to Lake Tahoe for two weeks, and I climbed from Truckee to Donner Pass Summit every day for a week. It wasn’t so far — maybe 20 miles — but it was a climb of about 2,000 feet, the way I went, to about 7,500 feet. This morning, I climbed from the flats to the hills (in Berkeley) twice.

I’ve also, rediscovered the joy of walking in recovering from the accident, and the richness of looking and stopping at slow speeds. I’ve met neighbors and their dogs I really had never been aware of. I experienced, in the early days of the pandemic, the quiet of far less traffic and the joy of walking in empty urban spaces. I’ve been in better and more frequent contact with friends from around the world through Zoom and phone.

While I certainly miss in-person human contact — a coffee, a drink, a dinner — I have not felt confined. That’s been the silver lining for those of us who have the extraordinary privilege and flexibility of working at home, within this unprecedented, grim context.

As we begin to recover from the horrors of the pandemic — so much is irreplaceable such as the loss or damage to loved ones — I feel our challenge going forward is rebuilding communities, a country and the world in a way that reflects our values, respects the environment and recognizes our common humanity.