With newly digitized slave ship logs, Berkeley Ph.D. student examines race, power — and literacy

"We're reconstructing history here," William Carter said of his geography Ph.D. research and collaboration with UC Berkeley's Disabled Students' Program.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

June 12, 2024

William Carter was in a National Archives reading room in the United Kingdom staring at a box of tattered pages covered in cursive writing, sea water stains and smears of blood. It smelled musty, and his hands became smudged turning the soot-covered pages.

Carter, a UC Berkeley Ph.D. candidate in geography, was mining these centuries-old slave ship logs in 2020 as part of his research into the transatlantic slave trade and what lessons from then might apply to our own understandings about race, literacy and power today.

But there was a problem: He couldn’t read a single sentence.

For even the most skilled readers, the faded, swooping lettering would be nearly indecipherable. But it was especially inaccessible for Carter, who has dyslexia and whose screen reader tools for written notes and published books didn’t work on 400-year-old slave ship logs.

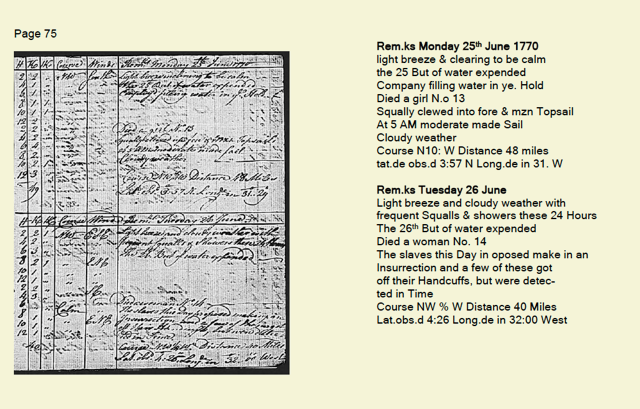

So in collaboration with UC Berkeley’s Disabled Students’ Program (DSP), Carter created a first-of-its-kind research solution to allow him to read these centuries-old materials. Carter finds logbooks and takes digital photos of the pages, which he then shares with DSP’s accessibility experts. That team works with a company to digitize the files in a layout mirroring the original documents, almost as if a deckhand in 1691 pulled out a typewriter or opened a Google Sheet.

The result is a file that Carter’s screen reader can interpret. For the first time in their history, these handwritten stories are available for Carter — and one day, he hopes, others — to listen to, analyze and write about.

“What I wanted to study had never been studied in the way I needed it to,” Carter said. “I wanted to study the geographies of the slave trade and the history of it, but the research process hadn’t been invented yet.

“We’re reconstructing history here.”

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

Through both his research and his fight against illiteracy, Carter’s work shows how the ability to read and the failure to recognize that people have other ways of knowing and sharing history have been weaponized against Black people as far back as the transatlantic slave trade.

In some ways, centuries after these documents were written, Carter said he faced the legacy of this weaponization of literacy himself. He was used to not being able to read common texts. But for the logs, and the long history attached to them, he felt he needed to “challenge the slave traders once more.” Doing so meant transcribing them, making them accessible, and engaging with them to see what the past could teach about the present.

That history matters now more than ever, Carter said. Literacy has been wielded as a weapon to elevate some and marginalize many through history, creating parallels between the slave trade and the literacy gap among Black people today, especially in California’s jails and prisons.

Slave ship logs, Carter contends, provide a window into the earliest days of this exploitation. Updated by white ship captains, the logs chronicle perilous ocean crossings built on a system of racialized violence. The hundreds of pages of logs he’s already translated describe how power is cultivated on a voyage, how words are weaponized and how rebellions begin.

“I see this process by the Disabled Students’ Program here as a deeply political intervention, of actually unraveling this racialized literacy through converting these materials,” Carter said. “And then, added to that, the fact I’m not reading them, but I’m listening to them in the tradition of the oral history of Africa, I think it’s kind of like a double whammy.”

When listening, you can’t skim past certain lines. Instead, you must endure each word, Carter said. Like listening to a podcast or an audiobook by a descriptive author, the stories and violence within the ledgers are jarring. The weather reports mixed with daily death tolls. Descriptions of enslaved people jumping overboard. The lashings meant to quell uprisings.

Their details linger.

“It’s very hard to ignore this torture when you’re actually listening,” Carter said.

Page 75 Rem.ks. Monday 25th June 1770, light breeze and clearing to be calm the 25th, bit of water expended. Company filling water. In the hold died a girl, No. 13. Squally, clewed into fore and mzn tops, at 5 a.m. moderate made sail.[Garbled latitude and longitude coordinates] Rem.ks Tuesday 26 June. Light breeze and cloudy weather with frequent squalls and showers these 24 hours. The 26th, bit of water expended. Died a woman, No. 14. The slaves this day in opposed make insurrection and a few of these got off their handcuffs, but were detected in time. [Garbled latitude and longitude coordinates]

Diagnosed with dyslexia at age 7

Carter, who is Black, grew up in a primarily white and middle-class area in South London. In elementary school, he struggled to fit in.

The difficulties stacked up when it came to classwork. Words on a book’s page swirled in an incomprehensible blur. He would routinely fail to finish his homework, leaving his teachers thinking he was lazy.

Courtesy of William Carter

Then, at age 7, he was diagnosed with severe dyslexia.

“They told me that my struggle had a name. And it was really helpful as a kid to know that I wasn’t lazy,” Carter said. “I think I’ve always had the trouble that I don’t perform my disability in a way that people expect.”

The diagnosis also meant he could develop strategies to succeed. A few years after his diagnosis, when he received his first laptop, he listened to author talks on YouTube so that he could speak intelligently about the books his high school teachers assigned.

Text-to-speech screen readers opened up an opportunity, but they were far from a panacea. They still are, Carter said. While they assist people with learning disabilities or visual impairments to read text, it’s difficult to use them to skim and scan a mountain of assigned books and journal articles in high school and college.

That frustration motivated him to question the status quo.

Courtesy of William Carter

While he was completing his undergraduate degree at the University of Bristol, Carter studied abroad at Berkeley in 2018. With a focus on ancient history and African American studies, he wondered how the long-ago past — often understood with just a few surviving texts — could reveal deep truths about past societies. He also wondered how the dearth of a historical record might intersect with race and Black identity today.

“I think that training in ancient history allowed me to have a better understanding of how to create histories when sources are limited,” he said.

During his study abroad program, he enrolled in a class taught by Jovan Scott Lewis, the chair of Berkeley’s Department of Geography and a prominent scholar who studies Black history, inequality and reparation.

The class left an impression on Carter, and Carter left a lasting impression on Lewis.

“I recall being so impressed by his ability to think creatively and sharply about the course’s questions around racialization and racism in such a grounded and global way,” Lewis said.

He encouraged Carter to apply to graduate school. It was the first time Carter said he truly felt encouraged to dream big with his research questions.

Courtesy of William Carter

Disabled Students’ Program steps in

Back in England, Carter finished his undergraduate degree at the University of Bristol. In January 2020, before the coronavirus ground the world to a halt, Carter interviewed for and ultimately won a Fulbright scholarship that returned him to Berkeley. Once at Berkeley, and when pandemic restrictions eased, his research involved a half dozen trips to archives around the world. From facilities in Washington, D.C., to Greenwich, England, Carter reviewed and scanned the once-waterlogged slave ship ledgers. In those pages, he knew there was a story the world had likely never heard, but should.

“I was looking at it,” Carter recalled, feeling frustrated. “But I couldn’t make heads or tails of it.”

So began a frustrating, yearslong translation puzzle. At Berkeley, the DSP assists individuals who have special needs. Initially, there were doubts about whether what Carter was asking the DSP to do — translate exceedingly complicated original documents — was a service it needed to, or even could, offer.

His dedication to accessibility reflects his commitment to inclusive research and sets a profound example for our academic community.

Martha Velasquez, DSP associate director

In his first years at Berkeley, he sent hundreds of emails and detailed reports totalling some 20,000 words to campus leaders and disabled student advocates outlining his research request and the historical precedent it would set, requiring that his documents be translated to uphold accessibility requirements. Throughout 2022 and 2023, he said he would sometimes walk away from conversations with campus leaders, doubting his ability to change how higher education was failing students with dyslexia.

By refusing to be made illiterate, Carter said he was resisting the same weaponization of literacy, illiteracy and the historical record that he studies form the era of the transatlantic slave trade.

His Berkeley research project pushed the boundaries of the accommodations the DSP typically provides. But finally, he found a team there that was willing to help, and it still helps.

When the DSP receives Carter’s ledgers, staff members review the pages and score the document on a scale of 1-3. Documents with a rating of 1 are relatively straightforward ones that an AI-based platform can easily read and convert into text for a screen reader to interpret. The DSP sends the more complex documents to a company that translates them manually and puts them on a digital spreadsheet that lines up exactly with the original records. A DSP team then spot-checks the sheets and sends the newly translated documents to Carter.

“Working with Will has truly been a privilege,” said Martha Velasquez, DSP associate director and auxiliary services manager. “His dedication to accessibility reflects his commitment to inclusive research and sets a profound example for our academic community.”

Courtesy of William Carter

Don’t ‘fix’ people. ‘Empower them.’

As a result, Carter has been able to study primary source documents in an entirely new way.

Lewis said he knew early on that Carter would excel academically. But he said he couldn’t have imagined how much effort Carter would invest in working to improve Berkeley’s policies and practices involving disability and other forms of access.

“In many ways, his dissertation research is a continuation of this story,” Lewis said, “with Will rethinking the terms of racial formation through a new narrative of the Atlantic slave trade and the notions and processes of othering that it produced.”

Carter also has championed efforts to support others who are neurodiverse. Dozens of conversations he had with campus leaders led to the formation in 2022 of the UC Berkeley Neurodiversity Initiative. It uses peer support and novel training techniques to make education at Berkeley more accessible to neurodiverse students.

Carter chairs the initiative, which is co-led by University Health Services Student Mental Health and the DSP. He said a major part of the project is for campus leaders and people with disabilities to be allies for students with learning disabilities. He also wants to educate faculty and staff members about ways that higher education institutions — including Berkeley, at times — alienate students like him by assigning inaccessible reading loads and unrealistic class expectations.

The goal should not be to “fix” people, Carter said. It should be to “empower them.”

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

“There are so many other dyslexic people who have similar stories, but we’re kind of erased because we’re seen as exceptions,” Carter said. “My case is not unique. My research process is innovative, yes. But my story isn’t unique. And in saying it’s unique, it kind of erases all the people that would benefit from something like this.”

Elena Schneider, an associate professor of history and a member of Carter’s graduate advisory committee, praised his outside-the-box thinking and his tenacity for finding research and accessibility solutions for neurodiverse scholars.

My research process is innovative, yes. But my story isn’t unique.

William Carter

“He isn’t afraid to explore uncomfortable or unorthodox ideas and see where they take him,” she said. “I’ve learned a lot from him in our scholarly dialogue over the last several years, and the entire campus has benefited from his much-needed activism. William is one of those students that makes me really thankful to be working at Cal.”

Today, midway through his graduate studies, Carter realizes that his research is only beginning. He has more archives to explore and more logs to pore through.

His preliminary findings have unearthed events aboard slave ships that have never before been known — events he hopes to one day publish papers about. Some of the findings, he said, may reshape the way scholars and the public understand the role of slave ship rebellions and the power of the words that describe them.

He hopes to one day digitize these slave ship logs and make them available for all scholars to examine for themselves — and importantly, to listen to without skimming.

Carter hopes to finish his dissertation by 2027.

“Ironically,” he said, “I’m going to write a book that I won’t be able to read.”