How the Zika virus gets into the developing fetus

Antibiotic found that blocks infection through both placenta and amniotic sac

July 18, 2016

UC San Francisco and UC Berkeley researchers have mapped out how the Zika virus infects the developing fetus, and have found an antibiotic that blocks these routes of infection, at least in human tissue culture and placental explants.

While this antibiotic may not be a practical way to prevent the Zika virus from entering the fetus, the new understanding of how the virus can get from mother to fetus and the placental model systems the researchers developed could lead to drugs that will be effective.

The findings, published today in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, comes as the virus, spread by mosquitoes and linked to a fetal deformity called microcephaly as well as Guillain-Barré syndrome in adults, has spread throughout South and Central America and is heading toward the southern U.S. Microcephaly, presumably caused when the virus crosses from an infected mother to the growing fetus in the first two trimesters of pregnancy, is characterized by a small head and serious brain damage leading to physical and learning disabilities and sometimes convulsions.

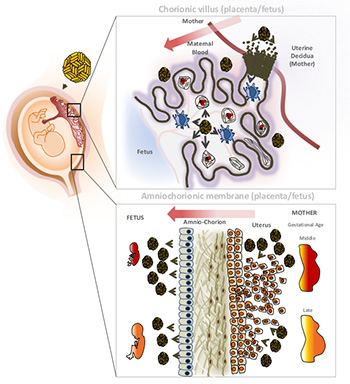

The UCSF/UC Berkeley team found that the virus has two potential routes to the developing fetus: a placental route established in the first trimester, and a route across the amniotic sac that becomes available only in the second trimester. The study of human tissue in the laboratory found that an older-generation antibiotic called duramycin blocked the virus from replicating in cells that are thought to transmit it along both routes.

Two possible ways for the Zika virus to infect the fetus: through the placenta (top) or the amniotic sac. Cytotrophoblasts (CTB) – cells in the chorionic villus – invade the mother’s uterus, connecting maternal and fetal blood supplies. The virus (gold balls) infects cells expressing a specific receptor called TIM1, thereby making its way from basal decidua cells to the chorionic villi to the fetal circulation. At bottom, parietal decidua cells allow the virus to get from the mother into the amniotic fluid and through that into the fetus. (Graphic by Henry Puerta-Guardo/UC Berkeley)

“Our paper shows that duramycin efficiently blocks infection of numerous placental cell types and intact first-trimester human placental tissue by contemporary strains of Zika virus recently isolated from the current outbreak in Latin America, where Zika virus infection during pregnancy has been associated with microcephaly and other congenital birth defects,” said study coauthor Eva Harris, a professor of infectious diseases and vaccinology at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health. “This indicates that duramycin or similar drugs could effectively reduce or prevent transmission of Zika virus from mother to fetus across both potential routes and prevent associated birth defects.”

Duramycin is an antibiotic that bacteria produce to fight off other bacteria. It is commonly used in animals and is in clinical trials for people with cystic fibrosis. Recent studies have shown it to be effective in cell culture experiments against dengue and West Nile virus, which are flaviviruses like Zika, as well as filoviruses, like Ebola.

“Very few viruses reach the fetus during pregnancy and cause birth defects,” said Lenore Pereira, a virologist and professor of cell and tissue biology in the UCSF School of Dentistry. “Understanding how some viruses are able to do this is a very significant question and may be the most essential question for thinking about ways to protect the fetus when the mother gets infected.”

The Zika virus, which the researchers examined in isolated cells and intact tissue explants, was found to infect several different placental cell types, including cell types within the placenta and outside the placenta in the fetal membranes. The scientists found that the epithelial cells of the amniotic membrane surrounding the fetus were particularly susceptible to Zika virus infection.

“This suggests that these cells play a significant role in mediating transmission to the fetus and supports the hypothesis that transmission could occur across these membranes independently of the placenta, especially in mid- and late gestation,” Pereira said. “The most severe birth defects associated with Zika infection — like microcephaly — seem to occur when a woman is infected in the first and second trimester. But there may be a range of lesser but still serious birth defects that occur when a woman is infected later in pregnancy.”

Other authors of the paper are postdoctoral fellows Henry Puerta-Guardo, Daniela Michlmayr and Chunling Wang of UC Berkeley and Takako Tabata, Matthew Petitt and June Fang-Hoover of UCSF.