Discovery of 4.4 million-year-old “Ardi” named Breakthrough of the Year

The journal Science has named the discovery of "Ardi," the oldest hominid skeleton ever found, its "Breakthrough of the Year 2009." An international team co-led by UC Berkeley's Tim White took 17 years to assemble and analyze the skeleton and thousands of other fossils found with it. The analysis, published in the Oct. 2 Science, revolutionizes our understanding of the earliest human ancestors appearing not long after the human lineage diverged from that of chimps.

December 17, 2009

The journal Science has named the discovery of “Ardi,” the oldest hominid skeleton ever found, its “Breakthrough of the Year 2009.”

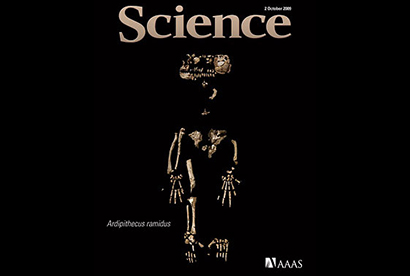

The discovery, reported in the journal’s Oct. 2 issue by an international team co-led by Tim White, a University of California, Berkeley, professor of integrative biology, surprised scientists because Ardi doesn’t look like a human or our presumed relative, the chimpanzee. Short for Ardipithecus ramidus, Ardi was a female who lived 4.4 million years ago in what is now the Afar region of Ethiopia.

The team took 17 years to assemble and analyze the skeleton and thousands of other fossils found with it, but the analysis, summarized in 11 papers, revolutionizes our understanding of the earliest human ancestors – those that appeared not long after the human lineage diverged from that of chimps, White said.

“From the response we’ve gotten from our colleagues, people are impressed by the diversity of the data sets,” White said. “It’s not just a skeleton, it’s the context of the many other individuals of that species and ecological information from all the other plants and animals and sediments that really lets you understand – in a way often not possible for these fossil discoveries – what that ancient world was like.”

Ardi’s skeleton was unique in having pelvic and foot bones that allowed the scientists to reconstruct how it walked, part of the cranium to judge its brain size, and parts of the jaw and a full set of teeth to ascertain its diet.

“The skeleton lets you understand what the hominid was like at a level of detail hard to achieve normally, simply because the data sets are usually not as comprehensive and complete,” White said.

Nineteen of the publications’ 47 authors trace their roots to UC Berkeley in some way, White said, and many UC Berkeley students were involved in the field and laboratory research. For more information on Ardi and the skeleton’s implications for human ancestry, visit:

- UC Berkeley’s NewsCenter

- Discovery Channel

- TIME magazine, which ranked the find number one on its list of the year’s Top 10 Scientific Discoveries

Or visit UC Berkeley’s Valley Life Sciences building, where the discoveries are currently featured.

White and the team are now preparing for their next field season in Ethiopia’s Middle Awash Valley, and will leave for a six-week trip starting in mid-January. At the trip’s conclusion in March, they will help move fossils they have unearthed since 1981 into a new research building, designed to protect Ethiopia’s precious antiquities, at the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa. They will also install an exhibit on Ardi, assembled by paleoanthropologist Gen Suwa of the University of Tokyo, in the museum’s public exhibition space.