Student parent, born in an Andean village, aims to go global in defense of the dispossessed

Consuelo Bustinza’s journey has taken her, so far, from a tiny Andean village to a place she describes as "a big ocean of knowledge and opportunities" where one learns to "solve big problems," UC Berkeley. Diminutive, energetic, and startlingly self-possessed, the campus senior aspires to one day be a voice for the dispossessed in the international arena.

January 15, 2010

Berkeley senior Connie Bustinza with her daughter, Athena. (Peg Skorpinski photo)

Berkeley senior Connie Bustinza with her daughter, Athena. (Peg Skorpinski photo)

‘A big ocean of knowledge’: On attending Berkeley and starting Gift to Life. (1:31 minutes)bustinza-ucb

‘Learn from those in power’: On her goals for the future. (57 seconds)bustinza-uun2

When members of the student organization Gift to Life hold their twice-weekly meeting in the Chavez Center, talk commonly flows to grant writing, outreach, and laboratory cheek swabs. That’s to be expected, as the group’s mission is to support indigenous Andean children afflicted with aplastic anemia, a serious blood disorder whose causes include exposure to toxic chemicals.

Yet busy Gift to Life members routinely pause together, as well, to breathe and center themselves before tackling their ambitious agenda, and to practice counting from uj to chunka in Quechua.

Why meditate at a student meeting, or learn how to count to ten as descendants of the Incas do? The short answer would be to connect their hearts with their minds, and to prepare for a trip to Peru and meetings with indigenous families.

Yet to really understand the group’s M.O. is to know its founder and driving force, Consuelo (Connie) Bustinza, whose journey has taken her, so far, from a tiny Andean village to a place she describes as “a big ocean of knowledge and opportunities” where one learns to “solve big problems,” UC Berkeley. Diminutive, energetic, and startlingly self-possessed, the campus senior aspires to one day be a voice for the dispossessed in the international arena. Large ambitions — especially for the parent of a four-year-old “who demands a lot” — yet entirely plausible to anyone who has experienced her in action.

“I can’t understand it, but I celebrate it,” Professor of Education John Hurst — in whose “Democracy and Education” course Bustinza launched Gift to Life (GTL) and recruited its first members — says of her “amazing ways of getting people to work with her.” Other students, he says, were drawn to her commitment to social justice and her improbable and inspiring personal story.

“I aggressively questioned her,” recalls one of those undergrads, Kate McHugh, a visiting student from the University of Western Australia. Convinced that Bustinza was the real deal, McHugh joined Gift to Life and ended up traveling with Connie and other GTL members on an 48-day summer 2009 trip to Peru that took them from Bustinza’s Andean hometown (via a 40-hour bus ride McHugh describes as “amazing and a nightmare”) to high government offices in Lima.

McHugh remembers laughing skeptically, outside the presidential palace, at Bustinza’s claim that they were about to be given an audience inside. Yet by day’s end the student delegation had spent several hours with a close presidential aide. In that meeting they pressed their concerns about the possible environmental causes of many children’s aplastic anemia — such as toxins left by the area’s many mining operations (described, for instance, in a Frontline feature) and the unregulated use of pesticides — and urged the government to do more to help indigenous children diagnosed with the ailment. “These crazy things do happen to Connie, because of her enthusiasm and her passion,” observes McHugh. “It’s infectious; you really get into it.”

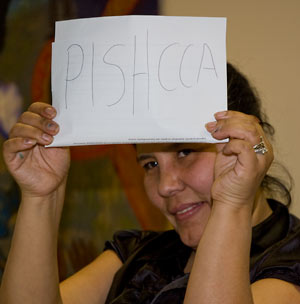

Bustinza teaches how to count in Quechua; pischcca, or pichqa, is “five.” (Cathy Cockrell/NewsCenter photo)

An unlikely journey

Bustinza, 31, began her life’s journey in Orccomayo, a Quechua-speaking peasant community in southern Peru, during the devastating conflict between Peruvian authorities and the Shining Path guerilla forces, and recalls witnessing “many injustices” as a child. In one instance she watched through cracks in a door as police intimidated a group of indigenous peasants. “I wish I could grow big; I wish I could be the president; I wish I could be the head of the military,” she remembers thinking. “Since I was little, I was always looking at the justice, unfairness, even in my family.”

Then, as now, her town was without electricity, clean running water, or schools — the nearest grade school being a day’s walk through the mountains. The fourth of eight children in a family directly impacted by the war (the details of which she is loathe to retell), Bustinza left home to help support her mother and siblings — moving first to a coffee plantation in Brazil, where she worked for three years as a maid, and later to Lima, where she earned money by washing clothes. At 19 she secured work abroad, doing childcare and housecleaning for a family in Marin County, Calif.

The next chapter of Bustinza’s story bears resemblance to the stateside experiences and misadventures depicted in the film “El Norte” — but with the protagonist unversed, in this case, in either Spanish or English, and illiterate in her native Quechua. (“I had no schooling, not even ABCs,” she says.) While riding a local bus, Bustinza noticed many Latinos with backpacks getting off at a particular stop. She followed them onto the campus of the local two-year College of Marin, where she was able to enroll in Saturday and evening classes in English, and began “tasting the sweetness of learning. I was,” she says, “so hungry for learning.”

What is aplastic anemia?

The Gift to Life student group works to offer hope and raise funds for the medical treatment of indigenous children in the Andes (like Bustinza’s nephew Arturo, pictured above with his mother) who suffer from aplastic anemia, a condition involving the under-production of blood cells. Symptoms include fatigue, susceptibility to infection, bleeding, rashes, dizziness, and irregular heart rate. If untreated, it can be fatal.

The Gift to Life student group works to offer hope and raise funds for the medical treatment of indigenous children in the Andes (like Bustinza’s nephew Arturo, pictured above with his mother) who suffer from aplastic anemia, a condition involving the under-production of blood cells. Symptoms include fatigue, susceptibility to infection, bleeding, rashes, dizziness, and irregular heart rate. If untreated, it can be fatal.Empowered by her studies, Bustinza eventually ran away from her domestic position. She landed a long series of jobs — as a dishwasher, gardener, cashier, barista, construction helper (for which she pretended to be a boy), and bank worker — and shared a crowded flat in San Rafael, doing her homework at night by the oven light. Eventually Bustinza earned an AA degree and transferred to Berkeley, where she is majoring in political economy, minoring in education and peace and conflict studies, and taking inspiration from figures like Gandhi and the Dalai Lama, and the ideal of peaceful conflict resolution.

If we “connect education and knowledge with compassion and love and mix it together, then a better world will absolutely wait for us ahead,” she believes.

Going back, looking ahead

Gift to Life’s trip to Peru — the Berkeley senior’s first return home since leaving in her teens — was emotional for Bustinza. When they visited Orccomayo, “I was shaking, so scared to see my mom after such a long time,” she recalls — wanting to thank her mother “for being so patient,” and to ask her forgiveness for electing an unconventional path.

Many immigrant children hold onto menial jobs so that they “send money to build a home,” Bustinza explains. But her experience at Berkeley has convinced her that she won’t realize her ambitions with a bachelor’s degree alone. Taking her education further, she believes, “will be more lasting.”

In her final semester on campus, Bustinza has many projects on her agenda: lining up students to take over leadership of Gift to Life; seeking a faculty sponsor for the group’s research in Peru this coming summer; and taking courses in public health, developmental economics, Vietnamese, and Spanish (the latter to improve her writing). She’s also busy applying to graduate programs in law, education, and public health — all of which pique her interest, as means to become an effective international advocate for the dispossessed.

Pipe dreams? Not if you “look back at her five or six year ago and think how improbable that transformation was,” ventures McHugh. “I can’t even imagine what she’s going to be in six years’ time. President or something?”

“I’m not one to romanticize: ‘Oh I am indigenous, so I am the victim,'” Bustinza insists. Rather, why not learn from those with skills and power, and use that knowledge to work for “a world where it’s equal,” where “there’s not these gaps”? That, and nothing less, is her plan.