Climate change: ‘Berkeley has a special obligation’

As a public university, Berkeley has a "special obligation" to reach far beyond its scientific expertise to seek solutions to global warming, Vice Chancellor for Research Graham Fleming told experts from across campus Thursday at the "Beyond Copenhagen" conference on international climate change negotiations.

February 1, 2010

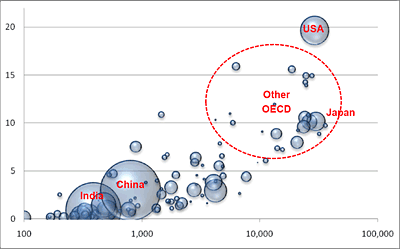

David Roland-Holst uses bubbles, big and small, on a chart to demonstrate a fundamental truth behind the near-crash-and-burn of global climate talks in Copenhagen in December.

The chart maps energy use against per capita income; the bubbles represent countries by population. Floating high on both axes are the medium-to-small bubbles of the United States and the rest of the industrialized world, rich countries that use a lot of energy. Hanging near the bottom are two giant bubbles, China and India, where both energy use and income are low — and rising.

ARE economist David Roland-Holst’s chart — which one of his graduate students calls his ‘demonic bubble bath’ — shows the tight relationship between energy use and prosperity, a key climate change issue. Based on World Bank and International Energy Agency data, the vertical axis plots per capita energy use in terajoules/year; the horizontal is per capita income as measured by the GDP. Bubble sizes represent population.

The relationship between income and energy use is no coincidence, and recognizing that simple fact is an essential part of getting past the current stalemate and finding answers to climate change, Roland-Holst, an adjunct professor in Berkeley’s Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, told the 100 or so climate-change experts gathered at Berkeley Thursday for “Beyond Copenhagen: Forging a Global Response to Climate Change.” The conference reviewed what happened at Copenhagen and looked at the future of ongoing negotiations over global warming.

Roland-Holst’s remarks were at the heart of a main point to surface at the conference — that climate change is a monumentally complicated problem whose solutions transcend science and politics and require sophisticated understandings of hugely disparate points of view and creative, innovative ways of thinking.

The university’s role

Berkeley, as the world’s top public university, has the kind of resources to help forge those solutions, several speakers pointed out. The conference took place under the aegis of the new Climate Energy Policy Institute (CEPI), which was founded within the last year to try to do just that. The institute, part of Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment, aims to bring together climate-change researchers and experts from disciplines all over campus to inform each other’s perspectives and use their interconnections to leverage their work into major influences on public policy, the economy, and business.

Held in the CITRIS building’s Banatao auditorium, CEPI’s conference invited perspectives from campus experts in law, political science, public policy, and energy research, most of whom attended the Copenhagen talks in December. A webcast of the conference can be viewed at CEPI’s website, calclimate.edu.

The next day, on CITRIS’s fourth floor, the dedication of Berkeley’s new i4Energy Center provided more evidence of the campus’s emerging climate-change synergy. The center brings together the CITRIS research institute, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the California Institute for Energy and Environment in a research alliance centered around breakthroughs in energy efficiency, a key component of climate solutions.

The center will connect energy technology coming out of Berkeley with the energy challenges facing the nation, CEPI director Dan Farber, chair of the Energy and Resources Group and professor of environmental law, said in opening the Thursday conference.

‘A special obligation’

Graham Fleming, vice chancellor of research and a chemistry professor, told the conference that climate change and the issues related to it will be the defining issues of the 20th century. The difficulty of finding solutions, he said, “doesn’t remove the obligation to try.”

“We as a public university have a special obligation in that regard,” Fleming added, “and one that one that I think the entire university with all its strengths needs to have as its top agenda item.”

Physical science is not enough, he said; researchers need to engage with those in public policy, law, economics, business, and industry to effect meaningful change.

Law dean Chris Edley said Berkeley’s contributions often don’t make it up the policy food chain, and that needs to change. “It’s a problem of uptake by the knuckleheads to whom we deliver ideas and research,” Edley said. “But it’s also a problem of the university for usually failing to take seriously the need to build the connections between the research, the policy implications of the research, and the institutional designs needed to actually execute those policies once adopted.”

He challenged Berkeley to “live up to its mission as a public institution” by reinventing itself, building on its multidisciplinary bent to solve problems, and creating the necessary new mechanisms of governance.

‘Energy is prosperity’

Among the welter of ideas advanced during two panel discussions, Roland-Holst’s slides illuminated — from an economist’s point of view — China’s stand against limits on greenhouse-gas emissions, which has been widely criticized as a significant reason for the failure of the Copenhagen talks to reach any major agreements.

The bubble chart makes the point that “energy is prosperity,” and economic growth is China’s top priority, asserted Roland-Holst. To maintain full employment, he said, China needs to generate 30 to 40 million new jobs every year. China’s power use will triple in the coming decades, mainly from coal-fired plants. And as China grows wealthier, car ownership will rise exponentially, from just 18 per 1,000 people today (in the U.S. the number is 800). The environment is a less immediate concern, he said.

“We have to recognize it, we have to understand it, we need more experience in trying to devise cooperative solutions among very discordant interest groups, multinationally,” Roland-Holst said. “Until we do that, there will be deaf ears in the negotiations.”

Among other perspectives offered during the conference:

The future of the United Nations climate-change process known as Copenhagen (December’s talks were the 15th, and a new round is planned for next December in Cancun, Mexico) is very uncertain, according to Rob Collier, a journalist and visiting scholar at the Center for Environmental Public Policy in the Goldman School of Public Policy.

The United States’ failure to adopt energy and emissions standards has been a drag on international progress, Collier said. Congressional passage of the Waxman-Markey energy bill would “say something to foreign governments.”

And even more important, he said, this year’s California gubernatorial election could have profound effects on the state’s own emissions limit legislation, AB32, passed in 2006 and considered a model both domestically and internationally. The two top GOP candidates have said they’ll suspend it if elected.

Reframing the issue

For progress to happen, the issue needs to be reframed from one of limits and costs to the economic potential of energy-efficient technology, according to John Zysman, professor of political science and co-director of the Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy.

The reason the U.S. is doing so little is no longer because of skepticism about climate change, but because of fear that change will prove expensive, said ARE economist Larry Karp. Setting a ceiling and floor on carbon prices in any future cap-and-trade system would go a long way toward reassuring business owners and engaging the business community in climate change.

Technology isn’t enough to solve the problem globally or domestically, and neither is righteous indignation, said ARE economist Michael Hanemann. It’s really a matter of convincing people. “It’s not technology, it’s behavior, and that requires persuasion and coordination and it’s complicated.”

The $64,000 question, Hanemann added, is, “What could you get agreement to that would be meaningful, and how do you get from here in January to there in December? This roadmapping needs to be done in the university and the research community.”