Fighting Nazism with the printed word

Resonating through a new Doe Library exhibit of Dutch clandestine art and literature published in defiance of Nazi suppression is the knowledge that, more than a half-century later, persecution, prison and even execution can still be the price of words printed on paper. On display are some 100 pamphlets, books, and artworks from a Bancroft Library special collection, one of the largest of its kind in the world. Driving home the exhibit's message will be a Regents Lecture on April 15 by Kader Abdolah, a Dutch writer forced to flee his native Iran for opposing the ayatollahs.

March 30, 2010

Resonating through a new Doe Library exhibit of Dutch art and literature published in defiance of Nazi suppression is the knowledge that, more than a half-century later, persecution, prison and even execution can still be the price of words printed on paper.

On display in the glass cases in Doe’s foyer, under the banner “Fighting Nazism With Words,” are some 100 pamphlets, books, broadsides, posters, prints and drawings selected from the Bancroft Library’s extraordinary collection of what’s known as Dutch clandestine literature.

Berkeley has one of the largest collections of such resistance works in the world — almost half of the roughly 1,000 pieces published during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands from 1940 to 1945. One of the Bancroft’s special collections, it was built by librarian James Spohrer.

Inaugurating the exhibit — and driving home the connection to the present day — will be a free public lecture by Kader Abdolah, a writer forced to flee his native Iran for opposing the ayatollahs during and after the 1979 revolution. Abdolah, who lives in the Netherlands and whose best-selling novels (written in Dutch) are barely veiled critiques of his homeland, will deliver a Regents Lecture at 5 p.m., Thursday, April 15 in the Morrison Library, just steps from where the exhibit is mounted.

Abdolah — his name is a pseudonym joining the names of two friends executed by the Iranian regime — has said that writing is his duty. “The ayatollahs have killed the dearest members of my family. I kill them back with literature,” he told the Times of London in a recent interview.

The power of words and images to expose and oppose tyranny is expressed throughout the exhibit of works printed in spite of Nazi censorship. The risks were extreme. An estimated 700 Dutch people lost their lives because of clandestine printing, according to Assistant Professor Jeroen Dewulf, the Queen Beatrix Chair of Berkeley’s Dutch studies program.

“It was very dangerous. Presses were noisy. There were not that many (presses) available, and the German authorities knew where to look,” says Dewulf, who along with Spohrer oversaw the creation of the exhibit. Dewulf, who is writing a book about Dutch clandestine literature, has collected many pieces on his own, which he has offered to the Bancroft collection.

Dutch resistance publishing

Resistance through publishing in the Netherlands began with a group of students from the university in Utrecht, who wanted to raise money to help provide food, shoes and clothing for Jewish children in hiding, according to Dewulf.

One of the first pieces was a 1941 broadside of the poem “The 18 Dead,” in which Dutch poet Jan Campert memorialized the first 18 Dutch people executed by the Nazis. Instead of selling hundreds, as they expected, the resisters sold thousands, and the idea caught on.

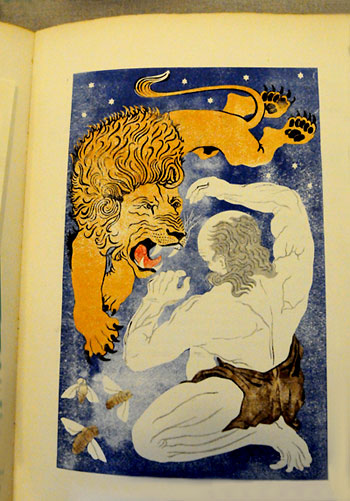

Print depicting the astrological sign Leo, in The Zodiac by Albert Helman. (Image courtesy of Bancroft Library)

Works printed during the Dutch resistance ranged from gorgeously artistic to rudimentary, and from direct attacks on the Nazis to incredibly subtle critiques. The exhibit, which will be on view through Aug. 31, contains examples of the full range. (The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank’s account of life as a Jewish teenager in hiding, is the best known work written during the occupation. But it’s not considered clandestine literature because it wasn’t printed until after the war, in 1947, two years after Frank died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.)

Among the most beautiful works is a book entitled De Dierenriem (The Zodiac), by Albert Helman, a major figure of the time. He accompanied full-page, full-color linoleum prints of the 12 signs of the zodiac with text set in handmade type that resembles calligraphy. (The Leo page is reproduced in the slide show illustrating this article.) Astrology wouldn’t seem to be a controversial topic, but Dewulf explains that it became popular during the resistance among people desperate for signs that their ordeal would end.

Another highly artistic piece — purchased by Dewulf in a used-book store in the Netherlands — is the “Turkenkalendar 1942,” a poetic calendar on fine, heavy paper with graphic designs that still seem modern. It was done by Hendrik Werkman, who Spohrer says was one of the greatest book designers of the 20th century and an artist who was executed by the Nazis for dedicating his talent to resistance work.

Dewulf tells a chilling tale: Werkman kept his critique of the occupation fairly subtle — the “Turkenkalendar,” for example, relates a parallel tale of war from history. In a raid on his studio, however, the Nazis found a collection of provocative cartoons (also represented in the exhibit) that ridiculed Adolf Hitler. They held Werkman responsible, though they weren’t his. He was dispatched to a Nazi camp the day that 12 inmates were to be executed for the killing of a German officer. One of the 12 escaped on the way to the execution ground, and Werkman was a convenient replacement. He was executed immediately.

Other pieces in the collection are “touching because they’re made of the cheapest materials, made under duress,” says Spohrer, who is librarian for the Germanic collections. “People didn’t have enough to eat, but they found a way to print news broadsides.”

Such broadsides about German losses at Stalingrad in 1942, for example, despite efforts to suppress the news, let a disheartened people know the Nazis weren’t unstoppable, Spohrer says.

Spotlighting a stellar special collection and library

Spohrer, who came to Berkeley as a grad student in comparative literature in 1981, went to work as a librarian while still a student. Since then, he’s built a good collection of Dutch resistance publications into a great one.

The exhibit came about because “we wanted to let people know that these collections exist,” Spohrer says. The collection can be viewed at the Bancroft Library.

Also, putting the exhibit together has proven to be a good way to teach students about using the library, both he and Dewulf say.

“Many students who come here have never been in a library,” Spohrer says. They’re used to doing their research online and are “wide-eyed” when they arrive on a campus with 11 million books, he adds.

Spohrer, Dewulf and a handful of students worked on the exhibit as a project of the Townsend Humanities Lab, a new online effort whose aim is to build interdisciplinary collaboration. It’s part of Berkeley’s Townsend Center for the Humanities and brings people together to pool information, texts, files, films — anything that can be digitized — online.

“The goal of the exhibit is to reach out to students and hope they get interested and might eventually use the collection,” says Dewulf.

He arrived on campus three years ago, eager to plunge into the collection himself.

“It’s a topic that, at least from an international perspective, has not received much attention yet,” he says.