Bancroft Library opens Mexico exhibit

A rare 1916 poster offering a reward for information leading to the arrest of Mexican Revolution leader Francisco “Pancho” Villa is just one of dozens of images and original documents in the University of California, Berkeley’s Bancroft Library’s “Celebrating Mexico” exhibit that opens this Thursday (Sept. 2).

August 31, 2010

A rare 1916 poster offering a reward for information leading to the arrest of Mexican Revolution leader Francisco “Pancho” Villa is just one of dozens of images and original documents in the University of California, Berkeley’s Bancroft Library’s “Celebrating Mexico” exhibit that opens this Thursday (Sept. 2).

During the Mexican Revolution, women served as nurses, aides to male soldiers, and soldiers themselves, and contributed a new perspective that influenced the growth of feminism in the 1920s and '30s in Mexico.

“Celebrating Mexico: The Grito de Dolores and The Mexican Revolution,” explores the complex history of Mexico, beginning with Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla’s 1810 speech that launched Mexico’s fierce fight for independence from Spain, and continuing with the Mexican Revolution against the established order of a century ago. The exhibit also will highlight indigenous rights, land reform, disparities between rich and poor, labor rights, education and press freedom.

A parallel exhibit opens on Sept. 20 at Stanford University’s Cecil H. Green Library. Together, the two events mark the first collaborative exhibition by the two Bay Area universities that each boasts superlative Mexican history collections.

The UC Berkeley exhibit will run from 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Monday through Friday through Jan. 14, 2011, and Stanford’s through Jan. 16, 2011. Both will be free and open to the public. Details about hours and locations at Berkeley and at Stanford are available online.

Charles Faulhaber, director of The Bancroft and a UC Berkeley professor of Spanish, said he is expecting large numbers of visitors, due in part to Mexico’s fascinating history, the libraries’ intriguing collections, and 2009 U.S. Census Bureau estimates that 37 percent of California’s population and 15.8 percent of the U.S. population are of Hispanic or Latino origins.

Jack von Euw, curator of The Bancroft’s pictorial collection and co-curator of The Bancroft’s exhibit with the library’s Western Americana curator Theresa Salazar, said the two libraries’ Mexican collections complement each other well. He described The Bancroft’s collection as particularly strong in terms of documents about the fight for independence, and one of the largest collections in the United States on the Mexican Revolution. Stanford holds extensive Mexican literary and film poster collections. Both institutions have vast collections of photos documenting the Revolution.

Von Euw said one particularly prized item in The Bancroft’s collection on the Mexican Revolution is the Villa wanted poster, which was issued the day that Villa and his men raided Columbus, New Mexico, in retaliation against a U.S. arms dealer. Some 80 of Villa’s band were killed, along with 18 Americans, with many wounded Villistas left behind.

Two of the most important documents in the Bancroft’s exhibit include Francisco Madero’s Manifiesto a la Nación Oct. 5, 1910, also known at the Plan de San Luis Potosi and Emiliano Zapata’s original Plan de Ayala of Nov. 28, 1911, which features his call for “Reform, Freedom, Justice and Law.

In the manifesto issued from exile in the United States, the pro-democracy intellectual Madero (who attended UC Berkeley from 1892-1893) declared the Mexican elections of 1910 void due to fraud, and demanded that dictator Porfirio Díaz step down as leader of Mexico. Madero would provide a peaceful transition of government until new elections could be held and would serve as president. His call for an uprising on Nov. 20, 1910, marked the beginning of the Mexican Revolution.

“Both these documents are very rare, distributed as broadsides to be posted in the fever of the moment; so they represent true high points in the exhibit. Their content changed the course of Mexican history,” said Salazar.

The Bancroft also will feature broadsides and posters illustrated by major Mexican artists such as José Guadalupe Posada, letters from Revolutionary figures including Villa, Zapata and Venustiano Carranza, and documents like an 1817 account by the governor of Zacatecas of the beginning of the fight for Mexican independence.

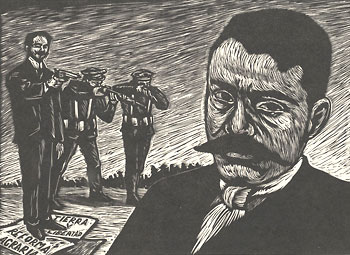

Firing-squad woodcut.

“Mexican history has always been one of Bancroft’s great strengths, going back to the days when Hubert Howe Bancroft himself was collecting books and archival materials in Europe and Mexico itself,” said Faulhaber. The University of California acquired The Bancroft’s collection in 1906, and continues supplementing its Mexico materials.

Today, The Bancroft archives contain papers spirited out of Mexico after the execution of Emperor Maximilian in 1867, items from Maximilian’s government, and newspapers from the Revolutionary period. The Bancroft also has one of the most comprehensive collections of official gazettes from Mexico, including the Diario de México from 1805, Latin America’s first daily newspaper. It also holds hundreds of personal, 20th-century Mexican diaries, journals and memoirs. The Bancroft also is home to oral histories of Revolutionary era leaders, as well as to materials relating to aid agencies’ work with some of the estimated 890,000 Mexican refugees who crossed the border into the U.S. between 1910 and 1920.

An illustrated, bilingual, 80-page catalog published by the UC Berkeley and Stanford libraries will be on sale at both institutions. It will include scholarly essays and a complete checklist of each library’s exhibition and 86 images drawn from the collections. The catalog will cost $20.

In tandem with the exhibit, The Bancroft, the Mexican Consulate of San Francisco and UC Berkeley’s Center for Latin American Studies will host an Oct. 22-23 symposium, “1810-1910-2010: Mexico’s Unfinished Revolution.” Historians, literary scholars, art historians and anthropologists will gather in Wheeler Hall’s Maude Fife Room to explore how Mexico’s independence and revolution were understood in their time as well as today, and what their implications are for contemporary Mexican politics and gender roles.

Adolfo Gilly, a professor of history at the Autonomous National University of Mexico and a political prisoner in Mexico’s Lecumberri prison from 1965 to 1971, will be the symposium’s keynote speaker. He is the author of “The Mexican Revolution: A People’s History” (2006), a far-reaching analysis of Mexico’s 1910 uprising.

Symposium panels will discuss four general subjects related to Mexico’s independence and revolution, including artists and intellectuals’ gender participation; religion, politics and armed rebellion; and the ongoing revolution inside and outside of Mexico. More details about the program are available online.

Related information:

• The Bancroft Library’s Mexico collection

• “Surprising new information on Pancho Villa comes to light in obscure Wells Fargo files at UC Berkeley” (1999 news release)

• Lectures and events at the campus’s Center for Latin American Studies