Masculinity at the intersection of College Avenue and Never Land

In The Lost Boys of Zeta Psi, anthropology professor Laurie Wilkie digs beyond Animal House stereotypes to unpack the everyday life of Berkeley fraternity circa 1900. Two campus excavations provided the foundation for the historic archaeologist's study.

September 21, 2010

When Berkeley anthropologist Laurie Wilkie began studying excavated debris from a campus fraternity, a 1996 Los Angeles Times story summed up her findings by advising readers to “Think Animal House circa 1920.”

The paper could hardly have been more wrong. In Wilkie’s new book, The Lost Boys of Zeta Psi (University of California Press), the professor of anthropology tells a story about a group of civilized young men around the turn of the 20th century who used expensive china imprinted with their fraternity’s crest, occasionally cross-dressed, drank beer from steins and pilsner glasses, and, ultimately, went on to prestigious, high-powered careers.

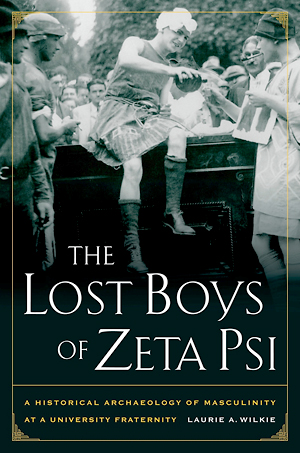

Laurie Wilkie displays a cup she recovered from Zeta Psi's Prohibition-era dumping site. (Wendy Edelstein/NewsCenter photo)

Wilkie didn’t want to impose a late 20th-century notion of fraternity life on the late-1800s and early-1900s Berkeley frat. Instead, she framed her book around Peter Pan. James Barrie’s popular play, which delighted theatrical audiences in England and America in the early 20th century, reflected the period’s gender tensions.

Wilkie found resonance between Peter’s jolly band and the fraternity members: “Never Land was a pause for the Lost Boys, a hiatus in growing up,” she says. “Just as the Lost Boys were only Lost Boys when they were in Never Land, you’re really only an active Zeta Psi brother when you’re in the house.”

Wilkie’s exploration of the fraternity began in 1995 with the campus law school’s northern expansion into the parking lot behind the Archaeological Research Facility at 2251 College Ave. Then an assistant professor in her first semester at Berkeley, Wilkie saw the backhoes from her office and the construction crew that found — and then tried to hide — a sizable cache of bottles.

The newest member of the department and its resident historic archaeologist, Wilkie was sent to investigate. It turned out the site had once been a dumping pit for the Iota chapter of Zeta Psi, the first fraternity formed west of the Rockies in 1870.

That first dig yielded a surprising number of unbroken artifacts: more bottles, ceramics (including examples bearing Zeta Psi’s crest), jars, inkwells, animal bones, buttons, pipe pieces, beer steins, cans, and a variety of household trash dating back to 1923.

“Any archaeological site has an interesting story,” she says. For Wilkie, the Zeta Psi site offered an opportunity to explicitly look at masculinity and manhood as part of the archaeology of gender. “Most of the field’s focus has been on the archaeology of women,” she explains.

One of Wilkie’s students researched the fraternity’s ceramics in a lab class and found they cost three times as much as the most expensive china sold by Sears. The Prohibition-era bottles at the site held near beers with little or no alcohol. “It became clear to me that these guys were not conforming to the stereotypes of what frat life is today,” says Wilkie.

Zeta Psi members drank their beer from steins and pilsner glasses, “the proper accoutrement,” says Wilkie. The upperclassmen taught their brothers how to behave in the business world. “This is where a young man separated himself from his mother’s household and learned how to be elegant,” she says.

Zeta Psi alums have served on the UC Board of Regents almost consistently since 1870. Some have presided over railroads, others founded banks and financial institutions, and one — James Budd — was elected governor of California. “That’s power,” notes Wilkie. “The old fraternities are elitist, protective of particular legacies, of race and sex and money. When we dismiss them as just a bunch of guys lying around drinking, then we’re letting that go unexamined.”

Wilkie was able to deepen her investigation of Zeta Psi in 2001, when the campus retrofitted the Archaeological Research Facility. The building rested on the footprint of Zeta Psi’s first house, which was built in 1876, and served as its second home between 1910 and 1956.

The Zetes’ (rhymes with eight) first house was equipped with running water and electricity, state-of-the-art features of the day. Although the ostentatious structure was fashionable when it was built, two decades later it was outdated. The Zetes’ house drew ridicule in the 1904 Blue and Gold and in subsequent volumes of the campus yearbook the frat wasn’t mentioned at all, a greater slight.

Entrepreneurial Zetes raised enough money to build a new house in 1910 where the first house once stood. Although the second building wasn’t much bigger than the first, it was designed as a fraternity house, a clearly masculine space, says Wilkie. A secret staircase led from the house’s exterior to a Z-shaped passageway to a chapter room where initiations took place and meetings were held.

While the Zetes battled the architectural shortcomings of their first house, expectations of manhood were shifting from the Victorian era, when men were engaged in “civilized behavior” such as debate societies. Women, the protectors of children, values, and morality, threatened the male status quo by seeking the vote. Men distanced themselves from domesticity by pursuing rugged leisure activities: bodybuilding, camping, hunting, and fishing.

“Men were conquering nature, while women were still stuck in corsets,” says Wilkie. Berkeley was one of the first co-educational institutions in the United States, and the gender battles on campus reflected changes in the larger social landscape.

Female undergraduates at Berkeley fought to take physical-education courses. “The argument was that men needed P.E. and women didn’t,” says Wilkie. Greek societies gave young men a refuge in which to respond to the social climate and shape new masculine identities, she says.

The dumping site provided only one sample confined to a small window of time. During the retrofit, she collected soil samples that corresponded to the construction of each building, the first structure’s demolition, and the occupation of the second house. The retrofit made Wilkie ‘s study more meaningful and gave her the basis for a classical archaeological comparison.

‘A hybrid discipline’

As a historic archaeologist, Wilkie uses “multiple lines of evidence” — different sources of data or analytical methods — to construct explanations about the past. Unlike traditional archaeologists who eschew texts and historians who rely solely on documents, Wilkie is part of “a hybrid discipline.”

At LSU, Wilkie wrote about African Americans who once lived on an antebellum Louisiana plantation. She has led other archaeological digs on campus, most recently the 2009 excavation of John Hinkel’s mansion and conservatory, the “Casa Hispana” boarding facility, and housing for World War II workers near People’s Park and parts of the Anna Head West parking lot.

Currently studying Mardi Gras beads’ origins and uses, Wilkie has become known as “the party archaeologist.” She was dubbed the “fraternity archaeologist” for her examination of Zeta Psi.

For the fraternity study, Wilkie drew on archival and oral historical sources in addition to the material she collected from the sites. In the case of Zeta Psi, “You can’t tell the story from just the archaeology. And you can’t tell the story from just the documents,” says Wilkie. “The archaeology triggers different questions than the documentary record and illuminates invisibilities and silences in them.”

“You need to think about who wrote the document, what their intention was, who wanted to see it, who kept it, who had access to it,” she says. The Zetes, for example, assembled scrapbooks to share information with brothers from the same generation and to record their history for the fraternity’s future generations.

‘The new masculinity’

In one scrapbook, Wilkie found a photo from 1892 in which two Zetes sit together on a bed. One man has tucked his foot under his friend’s calf as he gazes at him. When Wilkie looks at the photograph, she sees “two guys who have a loving friendship who are comfortable expressing affection in proximity. It wasn’t socially unacceptable for men to express their feelings for one another” back then, she says.

In the scrapbook photo, the men sit on an Indian blanket, “a marker of the new masculinity.” An animal pelt is draped over a bookshelf and a poster of a naked girl hangs on the wall. Those objects “attest to the new masculinity but there’s still this safety zone where male affection can be expressed,” says Wilkie.

Peter Pan, who can’t read, is “the shining emblem of the new masculinity,” says Wilkie. Wendy and Peter struggle, Wilkie says, because she wants to domesticate him and he refuses to see it. Wendy returns to Never Land once a year to do Peter’s housekeeping, because she desperately wants to be part of his life. “Peter Pan hasn’t been civilized at all,” says Wilkie.

By 1902, men were cross-dressing on campus, a practice that became prevalent by the 1930s and ’40s, says Wilkie. She found photographs of Zetes sporting coconut bras and hula skirts while wearing men’s socks and shoes. “They’re not trying to look like women. It’s not emulation. They’re definitely mocking women as if to say, ‘I’m not a girly man.’ ”

Such are the activities of college boys. “You get certain privileges as a college student when the march through time is arrested,” says Wilkie.

The Lost Boys decided to leave Never Land. They followed Wendy Darling back to London, were adopted, and grew up. “Barrie makes it plain in the footnotes of the play and in the book Wendy and Peter that this was a bad decision,” says Wilkie. “By embracing domesticity, they lead boring lives as bankers, stockmen, and middle management. And what do the Zeta Psi guys do? They go into banking, corporate jobs, and finance.”