Right or left? Brain stimulation can change the hand you favor

Each time we perform a simple task, like pushing an elevator button or reaching for a cup of coffee, the brain races to decide whether the left or right hand will do the job. But the left hand is more likely to win if a certain region of the brain receives magnetic stimulation, according to new research from UC Berkeley.

September 27, 2010

Each time we perform a simple task, like pushing an elevator button or reaching for a cup of coffee, the brain races to decide whether the left or right hand will do the job. But the left hand is more likely to win if a certain region of the brain receives magnetic stimulation, according to new research from the University of California, Berkeley.

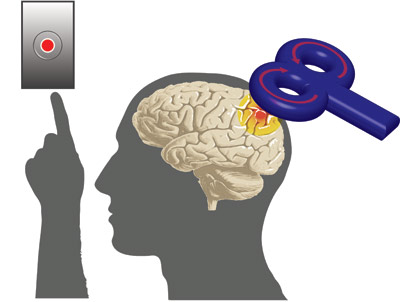

When the left posterior parietal cortex of the brain received magnetic stimulation, right-handed volunteers were more likely to use their left hand to perform simple one-handed tasks, UC Berkeley research shows. (Image courtesy of Flavio Oliveira)

UC Berkeley researchers applied transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to the posterior parietal cortex region of the brain in 33 right-handed volunteers and found that stimulating the left side spurred an increase in their use of the left hand.

The left hemisphere of the brain controls the motor skills of the right side of the body and vice versa. By stimulating the parietal cortex, which plays a key role in processing spatial relationships and planning movement, the neurons that govern motor skills were disrupted.

“You’re handicapping the right hand in this competition, and giving the left hand a better chance of winning,” said Flavio Oliveira, a UC Berkeley postdoctoral researcher in psychology and neuroscience and lead author of the study, published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study’s findings challenge previous assumptions about how we make decisions, revealing a competitive process, at least in the case of manual tasks. Moreover, it shows that TMS can manipulate the brain to change plans for which hand to use, paving the way for clinical advances in the rehabilitation of victims of stroke and other brain injuries.

“By understanding this process, we hope to be able to develop methods to overcome learned limb disuse,” said Richard Ivry, UC Berkeley professor of psychology and neuroscience and co-author of the study.

At least 80 percent of the people in the world are right-handed, but most people are ambidextrous when it comes to performing one-handed tasks that do not require fine motor skills.

“Alien hand syndrome,” a neurological disorder in which victims report the involuntary use of their hands, inspired researchers to investigate whether the brain initiates several action plans, setting in motion a competitive process before arriving at a decision.

While the study does not offer an explanation for why there is a competition involved in this type of decision making, researchers say it makes sense that we adjust which hand we use based on changing situations.

“In the middle of the decision process, things can change, so we need to change track,” Oliveira said.

In TMS, magnetic pulses alter electrical activity in the brain, disrupting the neurons in the underlying brain tissue. While the current findings are limited to hand choice, TMS could, in theory, influence other decisions, such as whether to choose an apple or an orange, or even which movie to see, Ivry said.

With sensors on their fingertips, the study’s participants were instructed to reach for various targets on a virtual tabletop while a 3-D motion-tracking system followed the movements of their hands. When the left posterior parietal cortex was stimulated, and the target was located in a spot where they could use either hand, there was a significant increase of the use of the left hand, Oliveira said.

Other coauthors of the study are Jörn Diedrichsen from University College London, Timothy Verstynen from the University of Pittsburg and Julie Duque from the Université Catholique de Louvain in Belgium.

The study was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Belgian American Educational Foundation.