Burma’s voice of liberty, struggling to be heard

Speaking to a Berkeley audience via cellphone from Burma, Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of her country's democracy movement, had to contend with static and feedback squeals. Even so, her message came through loud and clear.

March 8, 2011

From the sound of her voice, one might have thought Burma was far more than 8,000 miles away. Carried by cellphone, then amplified in Wheeler Auditorium and live-streamed over a password-protected Internet connection, it struggled through volume problems, static, microphone buzz and feedback squeals. Often, the words were barely intelligible.

But Aung San Suu Kyi, who has spent 15 of the past 21 years under house arrest at the hands of Burma’s military dictatorship, is living proof that it isn’t necessary to be seen, or heard, to inspire.

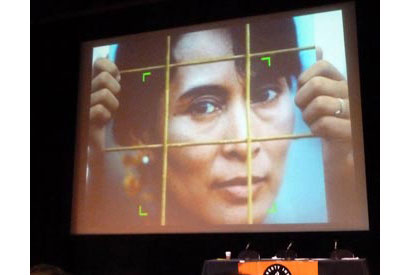

As she spoke, images of Aung San Suu Kyi were projected on a screen

On Monday night, the leader of Burma’s democracy movement — and winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize — spoke to an audience of several hundred students, activists and members of the Bay Area’s Burmese community in a phone interview arranged by facilitators of a student-run DeCal class on Burmese politics. The event was available online to those who had been given a password, a precaution meant to discourage possible interference from the Burmese government.

At one point in the 40-minute interview, Suu Kyi recounted how, during 2007’s so-called “Saffron Revolution” — the nonviolent protests led by Buddhist monks and brutally crushed by the ruling junta — she was preparing a banner of support to display on her gate when she heard distant chanting. The chants grew louder, and finally she saw the procession of monks and pro-democracy activists.

The protesters stopped outside her house, and she recognized some young activists from her own political party, the National League for Democracy. But the terms of her detention prohibited her from stepping outside the gate, and she complied. “I’m a very law-abiding citizen,” she said.

“I was not supposed to communicate with anybody outside, so I didn’t actually talk to them,” she added. “But I smiled at them.”

Now 65, Suu Kyi was released in November, this time after seven years of house arrest, a week after elections that guaranteed the junta’s hold on power for another five years. Her father, nationalist leader Aung San, was assassinated shortly before the country won its independence from Britain in 1947. Two years after a nationwide uprising in 1988, a resounding election victory by her NLD party was voided by the ruling generals.

The party boycotted the 2010 elections, prompting the junta to dissolve it.

On Monday, Suu Kyi patiently answered questions from Berkeley students including Michael Gaw and Wayland Blue, co-facilitators of the DeCal class, and from a dozen or so members of the audience, some of whom could barely contain their excitement at getting to speak with her.

To a student who wondered what it might take for Asia to share in the democratic fervor erupting in places like Egypt and Libya, Suu Kyi counseled the need to put aside petty differences to push for democracy worldwide. “I would be so appreciative,” she said, “if all the freedom-loving people could get together, work together, not just for a particular country or a particular people, but for all the people in all the countries that suffer from oppression.”

To a student from Burma who asked what she and others like her could do, she said, “Please don’t forget your roots,” and reminded her that young people in Burma have not had the educational opportunities available to those in other parts of the world. (Suu Kyi herself studied at Oxford.)

“I would so much appreciate it if young people in the United States, young people from Burma, would concentrate on helping young people in Burma get a better education,” she said, adding that in addition to moral support, “I would like you to do something practical,” such as assisting with educational funding.

Min Zin

Before her interview, Min Zin, a Burmese journalist who went into hiding in 1989 to avoid arrest — and is now earning his master’s degree at the Graduate School of Journalism, despite having been expelled from high school for his activism — described the extreme poverty, repression and brutality under Burma’s generals, who renamed the country Myanmar in 1989.

Min Zin, who fled the country in 1997, hailed what he called a “spirit of resistance” inside his native country, and told the audience how activists there would find strength in the face of military might by linking arms during protests.

He urged his listeners to “share your energy, share your strength, so that people in Burma can link up with you.”

The event marked the first time Suu Kyi has addressed an audience at Berkeley. Gaw said he and his fellow DeCal facilitators had heard her express interest in connecting with college students and the younger generation following her most recent release. They’ve been trying to arrange the talk since winter break, and got confirmation less than two weeks ago.

“We figured if it’ll be anywhere in America, it should start at Cal,” he explained, adding that Berkeley is the only university in the country with a class — even a student-run one — on Burmese politics.