Historian of science Roger Hahn dies at 79

Roger Hahn, emeritus professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley, and a leader in shaping the academic field of the history of science, died unexpectedly on May 30 in New York City.

August 8, 2011

Roger Hahn, emeritus professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley, and a leader in shaping the academic field of the history of science, died unexpectedly on May 30 in New York City. He was 79.

Now widely recognized as a significant field of study, the history of science was an emerging discipline when Hahn, in 1953, was among the first students to graduate from Harvard College with majors in both science (physics) and history.

Through his studies in Paris at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, as a Fulbright Scholar, and then at Cornell University, where he earned his Ph.D., Hahn developed a keen interest in the relationship between science and society.

Moving away from the established approach of teaching scientific development as a series of isolated chronological discoveries, Hahn pursued an integrated view of the development of scientific ideas and institutions as reflective of the socio-political, philosophical, human and other dimensions of their times.

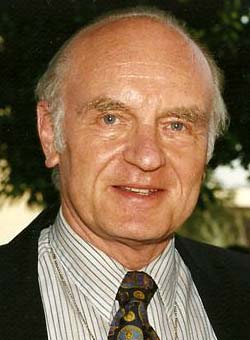

Roger Hahn

“He put his stamp on the field in a way that became a model,” said Cathryn Carson, UC Berkeley associate professor of the history of science. “From the start, he cared for questions about science and society that have since become fashionable, and framed them with care, thought and deep academic grounding.”

One of his most notable and influential works, “The Anatomy of a Scientific Institution. The Paris Academy of Sciences 1666-1803” (1971) provides a comprehensive account of the elite Paris Academy of Sciences from its founding to its dissolution as a royal institution during the French Revolution, and its subsequent revision in the Napoleonic era. Hahn described the Academy as “the anvil on which the often conflicting values of science and society are shaped into a visible form.”

Hahn was born in Paris on Jan. 5, 1932. His family fled to New York in 1941 to escape Nazi oppression. After graduating magna cum laude from Harvard College in 1953 and earning an M.A.T. in Education from Harvard the following year, Hahn served in the U.S. Army and was stationed outside of Paris, at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE).

In 1961, Hahn accepted a position in the Department of History at UC Berkeley where he researched, published, taught and participated broadly in both UC and academic life for more than 50 years.

“Hahn’s passing is a grievous loss to the campus community,” said Erich Gruen, emeritus professor of history and a longtime colleague of Hahn’s. “He was unfailingly supportive and considerate to younger colleagues, a gentle man who never demanded but always commanded respect. At department meetings, his was an independent voice, consistently displaying sound, well-informed, and balanced judgment; never driven by ideology or inflexible opinion.”

Hahn’s academic interests frequently took him to Europe, where his fluency in five languages facilitated research throughout the continent.

He is equally known for his work on the late 18th and early 19th-century French scientist and statesman Pierre Simon Laplace, who is considered one of the greatest scientists of the Enlightenment and “France’s Sir Isaac Newton.” Most of LaPlace’s personal papers and library had been destroyed in a fire, so Hahn embarked on a life-long quest to uncover Laplace’s correspondence with scientists and colleagues throughout Europe, thereby reconstructing the evolution of Laplace’s thinking and discoveries. The publication of Hahn’s biography of Laplace, “Pierre Simon Laplace 1749-1827: A Determined Scientist” was widely acclaimed. At his death, Hahn’s work on the collected letters of Laplace was nearing publication.

In the early 1970s, when James D. Hart, former director at UC Berkeley of The Bancroft Library, proposed the establishment of a History of Science Collection, Hahn became its unofficial curator and special assistant to Hart. He pursued rare books, manuscripts and the personal papers of notable scientists,obtaining important additions to the collection. Most importantly, Hahn was largely responsible for arranging the acquisition by The Bancroft of the remaining Laplace papers.

“Hahn had a keen, ongoing interest in the antiquarian trade in books and manuscripts in the history of science,” said Peter Hanff, deputy director of The Bancroft. “He read catalogues and made referrals continually, even in his retirement.” Hahn served on The Bancroft’s Council of the Friends and also served on the advisory board of The Bancroft’s Regional Oral History Office, gathering and preserving oral histories from important scientific figures in the Bay Area.

Hahn was deeply committed to teaching and advising his post-graduate, graduate, and undergraduate students. His courses covered the broad sweep of the history of science—from Aristotle to the Atom bomb. One of his most innovative courses was an interdisciplinary class on Renaissance engineers, co-taught by four UC Berkeley professors: an historian, an architect and two engineers.

At UC Berkeley, Hahn was a founding member and served as director of the Office for History of Science and Technology at from 1993 to 1998. He also served as co-chair of the French Studies Program from 1987 to 1990, and was chair of the selection committee for the France-Berkeley Fund. Throughout his career Hahn served on numerous committees in the Department of History, the College of Letters and Science, the Academic Senate, the University of California system, and the Office of the President.

“Roger was the perfect colleague,” said John Heilbron, an emeritus professor of history and a friend and colleague of Hahn’s for nearly 30 years. “He was also a very good academic citizen; interested, friendly, knowledgeable, challenging –the sort of person, now increasingly rare, who helps to make the university greater than the sum of its parts.”

Among Hahn’s many honors and appointments, he was twice named a National Science Foundation Fellow and was named to the Council of the History of Science Society. Hahn was decorated in 1977 with the French government’s high academic honor, Officier de l’Ordre des Palmes Académiques, for his promotion of cultural and academic exchange between France and the United States and for his classic study of the French Academy of Sciences. In France, he held appointments at the Collège de France, the Sorbonne and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

He was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and member of the Académie Internationale d’Histoire des Sciences, serving as its vice president in 2005. Hahn was also a fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies and president of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies and of the West Coast History of Science Society. He was an active participant and a member of the advisory council for Humanities West.

“Above all, Roger was a true scholar, an excellent teacher, a wonderful, warm human being with a fine sense of humor, and a dear friend,” said James Casey, a UC Berkeley engineering professor who was collaborating with Hahn on a publication on the theory of plasticity of metals. “His deep study of history had taught him to be philosophical about life, people, and politics. He had a realistic, balanced, view of humanity.”

Roger Hahn is survived by his wife, Ellen Hahn of Berkeley, Calif., daughters Elisabeth Hahn of New York City, and Sophie Hahn Bjerkholt of Berkeley, and three grandchildren. He is also survived by his brother, Pierre M. Hahn of San Francisco.