Cellphone, GPS data suggest new strategy for alleviating traffic tie-ups

Tired of sitting in rush hour traffic? A new study demonstrates that asking everyone to cut their driving is only moderately effective in reducing congestion, but asking those in specific communities - those that contribute most to bottlenecks - may work better.

December 20, 2012

Asking all commuters to cut back on rush-hour driving reduces traffic congestion somewhat, but asking specific groups of drivers to stay off the road may work even better.

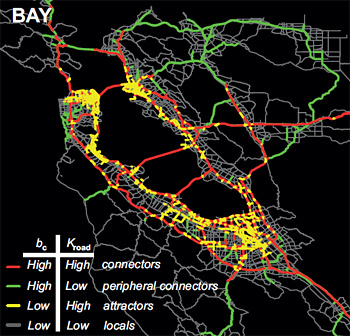

San Francisco Bay Area freeways colored according to how popular they are as connectors between other roads (bc) and the number of geographic areas that contribute to traffic on a particular road (Kroad).

The conclusion comes from a new analysis by engineers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley, that was made possible by their ability to track traffic using commuters’ cellphone and GPS signals.

This is the first large-scale traffic study to track travel using anonymous cellphone data rather than survey data or information obtained from U.S. Census Bureau travel diaries. In 2007, congestion on U.S. roads was responsible for 4.2 billion hours of additional travel time, as well as 2.8 billion gallons of fuel consumption and an accompanying increase in air pollution.

The study, which appears today (Thursday, Dec. 20) in the open-access online journal Scientific Reports, demonstrates that canceling or delaying the trips of 1 percent of all drivers across a road network would reduce delays caused by congestion by only about 3 percent. But canceling the trips of 1 percent of drivers from carefully selected neighborhoods would reduce the extra travel time for all other drivers in a metropolitan area by as much as 18 percent.

“This is a preliminary study that demonstrates that not all drivers are contributing uniformly to congestion,” said coauthor Alexandre Bayen, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science and of civil and environmental engineering at UC Berkeley. “Reaching out to everybody to change their time or mode of commute is thus not necessarily as efficient as reaching out to those in a particular geographic area who contribute most to bottlenecks.”

He noted, however, that while the researchers’ computer modeling suggests that this strategy works, it remains for policy makers to decide whether it is practical or desirable to target specific geographic areas.

San Francisco and Boston

The study was performed in Boston and San Francisco, two cities with radically different commute patterns. In Boston, the freeways spread radially outward to the suburbs, with concentric rings of freeways intersecting them like a spider web. In San Francisco, the freeways encircle San Francisco Bay and are connected by six bridges.

Lead researcher Marta González, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at MIT, and former MIT postdoc Pu Wang, now a professor at Central South University, used three weeks of cellphone data to obtain information about anonymous drivers’ routes and the estimated traffic volume and speed on those routes both in Boston and the San Francisco Bay Area. They inferred a driver’s home neighborhood from the regularity of the route traveled and from the locations of cell towers that handled calls made between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. They combined this with information about population densities and the location and capacity of roads in the networks of these two metropolitan areas to determine which neighborhoods are the largest sources of drivers on each road segment, and which roads these drivers use to connect from home to highways and other major roadways.

To double-check this method, Bayen and graduate student Timothy Hunter used a different set of data obtained from GPS sensors in taxis in the San Francisco area to compute taxis’ speed based on travel time from one location to another. From that speed of travel, they then determined congestion levels.

The results produced by both methods show good agreement, Bayen said.

“One of the novelties of this work is that it used two very different sources of cellphone data to complete the work: cell tower data, which is relatively inaccurate for positioning, but provides good information about people’s approximate location and routing, and GPS data, which provides very accurate positioning information, useful for precise congestion level assessment,” he said.

In the San Francisco area, for example, they found that canceling trips by drivers from Dublin, Hayward, San Jose, San Rafael and parts of San Ramon would cut 14 percent from the travel time of other drivers.

“This has an analogy in many other flows in networks,” González said. “Being able to detect and then release the congestion in the most affected arteries improves the functioning of the entire coronary system.”

Because the new methodology requires only three types of data — population density, topological information about a road network and cellphone data — it can be used for almost any urban area.

“In many cities in the developing world, traffic congestion is a major problem, and travel surveys don’t exist,” González said. “So the detailed methodology we developed for using cellphone data to accurately characterize road network use could help traffic managers control congestion and allow planners to create road networks that fit a population’s needs.”

Katja Schechtner, head of the Dynamic Transportation Systems group at the Austrian Institute of Technology and a visiting scholar at the MIT Media Lab, is a co-author on the Scientific Reports paper with González, Wang, Bayen and Hunter.

The study was funded by grants from the New England University Transportation Center, the NEC Corporation Fund, the Solomon Buchsbaum Research Fund and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Wang received funding from the Shenghua Scholar Program of Central South University.

RELATED INFORMATION

- Understanding Road Usage Patterns in Urban Areas (Scientific Reports, Dec. 20, 2012))

- Cellphone data helps pinpoint source of traffic tie-ups (MIT press release)

- Alexandre Bayen’s Web site