Discovery opens the door to a potential ‘molecular fountain of youth’

UC Berkeley researchers were able to turn back the molecular clock of blood stem cells of old mice by infusing them with a longevity gene. The experiment rejuvenated the aged stem cells' regenerative potential, providing new hope for the development of targeted treatments for age-related degenerative diseases.

January 31, 2013

A new study led by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, represents a major advance in the understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind aging while providing new hope for the development of targeted treatments for age-related degenerative diseases.

Older and fitter? New findings from a UC Berkeley-led study could have implications for the development of treatments for age-related degenerative diseases.

Researchers were able to turn back the molecular clock by infusing the blood stem cells of old mice with a longevity gene and rejuvenating the aged stem cells’ regenerative potential. The findings were published online today (Thursday, Jan. 31), in the journal Cell Reports.

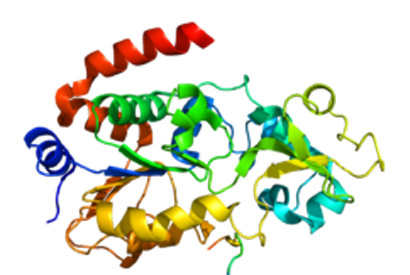

The biologists found that SIRT3, one among a class of proteins known as sirtuins, plays an important role in helping aged blood stem cells cope with stress. When they infused the blood stem cells of old mice with SIRT3, the treatment boosted the formation of new blood cells, evidence of a reversal in the age-related decline in the old stem cells’ function.

“We already know that sirtuins regulate aging, but our study is really the first one demonstrating that sirtuins can reverse aging-associated degeneration, and I think that’s very exciting,” said study principal investigator Danica Chen, UC Berkeley assistant professor of nutritional science and toxicology. “This opens the door to potential treatments for age-related degenerative diseases.”

Chen noted that over the past 10 to 20 years, there have been breakthroughs in scientists’ understanding of aging. Instead of an uncontrolled, random process, aging is now considered highly regulated as development, opening it up to possible manipulation.

“A molecular fountain of youth”

“Studies have already shown that even a single gene mutation can lead to lifespan extension,” said Chen. “The question is whether we can understand the process well enough so that we can actually develop a molecular fountain of youth. Can we actually reverse aging? This is something we’re hoping to understand and accomplish.”

Chen worked with David Scadden, director of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

Sirtuins have taken the spotlight in this quest as the importance of this family of proteins to the aging process becomes increasingly clear. Notably, SIRT3 is found in a cell’s mitochondria, a cell compartment that helps control growth and death, and previous studies have shown that the SIRT3 gene is activated during calorie restriction, which has been shown to extend lifespan in various species.

To gauge the effects of aging, the researchers studied the function of adult stem cells. The adult stem cells are responsible for maintaining and repairing tissue, a function that breaks down with age. They focused on hematopoietic, or blood, stem cells because of their ability to completely reconstitute the blood system, the capability that underlies successful bone marrow transplantation.

The researchers first observed the blood system of mice that had the gene for SIRT3 disabled. Surprisingly, among young mice, the absence of SIRT3 made no difference. It was only when time crept up on the mice that things changed. By the ripe old age of two, the SIRT3-deficient mice had significantly fewer blood stem cells and decreased ability to regenerate new blood cells compared with regular mice of the same age.

What is behind the age gap? It appears that in young cells, the blood stem cells are functioning well and have relatively low levels of oxidative stress, which is the burden on the body that results from the harmful byproducts of metabolism. At this youthful stage, the body’s normal anti-oxidant defenses can easily deal with the low stress levels, so differences in SIRT3 are less important.

“When we get older, our system doesn’t work as well, and we either generate more oxidative stress or we can’t remove it as well, so levels build up,” said Chen. “Under this condition, our normal anti-oxidative system can’t take care of us, so that’s when we need SIRT3 to kick in to boost the anti-oxidant system. However, SIRT3 levels also drop with age, so over time, the system is overwhelmed.”

Old mice, new blood

To see if boosting SIRT3 levels could make a difference, the researchers increased the levels of SIRT3 in the blood stem cells of aged mice. That experiment rejuvenated the aged blood stem cells, leading to improved production of blood cells.

It remains to be seen whether over-expression of SIRT3 can actually prolong life, but Chen pointed out that extending lifespan is not the only goal for this area of research. “A major goal of the aging field is to utilize knowledge of genetic regulation to treat age-related diseases,” she said.

Study co-lead author Katharine Brown, who conducted the research as a UC Berkeley Ph.D. student in Chen’s lab, said SIRT3 has some potential in this regard.

“Other researchers have demonstrated that SIRT3 acts as a tumor suppressor,” said Brown. “This is promising because, ideally, one would want a rejuvenative therapy where you could increase a protein’s expression without increasing the risk of diseases like cancer.”

The other co-lead author of this study is Stephanie Xie, a post-doctoral fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Regenerative Medicine at the time of the study. Xie is now a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Toronto.

A number of funding sources supported this study, including the Searle Scholars Program, the National Institutes of Health and the Siebel Stem Cell Institute.