Garniss Curtis, pioneer of precision fossil dating, has died at 93

UC Berkeley geologist Garniss H. Curtis, a professor emeritus of earth and planetary science who pioneered the use of radioactive isotopes to date relatively young rocks, thereby providing the first solid timeline for human evolution, died Dec. 18 in Orinda, Calif., at the age of 93.

February 26, 2013

Geologist Garniss H. Curtis, a professor emeritus of earth and planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley, whose pioneering use of radioactive isotopes to date relatively young rocks provided the first solid timeline for human evolution, died Dec. 19* in Orinda, Calif., at the age of 93.

Garniss Hearfield Curtis, professor emeritus of earth and planetary science.

Curtis collaborated with late UC Berkeley professors John Reynolds, a physicist, and Jack Evernden, a seismologist, to take advantage of the radioactive decay of potassium into argon in volcanic rock to determine how long ago the rock formed. Using this potassium-argon method, they established precise dates for recent geologic time periods that allowed Curtis to assign dates to fossilized human remains and prove they were much older than once thought.

“Reynolds developed a precise way to date meteorites in the 1950s, but it was Garniss who adapted the technique to work on geological problems,” said G. Brent Dalrymple, emeritus professor and former dean of the College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University in Corvallis. He first met Curtis while obtaining his Ph.D. at UC Berkeley in the 1960s.

Since the late 19th century, radioactive isotopes such as uranium and potassium have been used to date billion-year-old rocks, but dating young rocks was a challenge because the radioactive decay products in such rocks are present in minuscule quantities. Using then-new ultra high vacuum systems combined with mass spectrometry, UC Berkeley researchers were finally able to count these atoms and provide precise dates on young rocks.

“Garniss was the first to show that you could date things younger than a couple of million years, and he teamed up with the Leakeys to date their finds in Olduvai gorge in Kenya,” said Curtis’s former student Paul Renne, now director of the Berkeley Geochronology Center, which Curtis founded. “His major contribution was putting numbers on the timescale of human evolution.”

“This work formed the quantitative ground work for paleoanthropology and human evolutionary history by providing a set of ‘clocks’ with which to read and hence interpret past events in proper sequence,” wrote geologist George Brimhall in a 1989 letter recommending Curtis for a Berkeley Citation, an honor bestowed by the chancellor for distinguished or extraordinary service to the university.

Java Man

Among Curtis’s accomplishments was a discovery in the late 1990s with UC Berkeley geologist Carl Swisher that startled paleoanthropologists. They determined that the million-year-old human ancestor Homo erectus survived in Asia until some 50,000 years ago, meaning that this hominid species and modern humans, Homo sapiens, coexisted. The idea that humans did not evolve along one single lineage, but instead, branched off into ancestors that included some dead ends, with only modern humans surviving to the present, is well established today.

The story of this discovery and its implications was detailed in the 2001 book “Java Man: How Two Geologists Changed Our Understanding of Human Evolution,” by Swisher, Curtis and writer Roger Lewin.

Once he had adopted Reynolds’ techniques, Curtis “was always coming up with ideas about new things to date, from geological periods to glaciation,” Dalrymple said. He would seek out colleagues with fossils from eras he was interested in and then date the volcanic rocks above and below the remains’ deposits to assign a precise date.

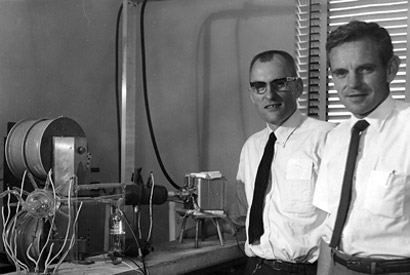

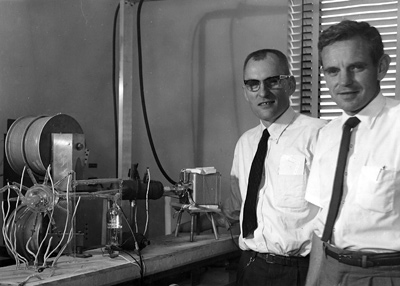

Garniss Curtis (right) and Jack Evernden with a mass spectrometer they used to determine the age of rocks, ca. 1960. Photo by J. Hampel/UC Berkeley.

In 1960, for example, Curtis and Evernden rocked the anthropological world when they used the potassium-argon method to establish the 1.85 million year age of Mary Leakey’s 1959 Olduvai Gorge fossils of the early human ancestor Zinjanthropus, pushing back the then-accepted age of the Pleistocene by 1 million years.

Upon his retirement in 1989, Curtis joined paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson at the Institute of Human Origins in Berkeley, where Curtis established a geochronology laboratory to continue his work with potassium-argon dating and a refinement called argon-argon dating. He and his colleagues provided dates for Johanson’s discoveries of human ancestors in Africa, as well as for discoveries by Mary and Richard Leakey and UC Berkeley paleoanthropologist Tim White. The Berkeley Geochronology Center, as the laboratory was called, became independent of the institute in 1994, and is today one of the top laboratories for dating in the world.

Curtis’s friendship with philanthropists Gordon and Ann Getty ensured continued support for the center after the institute and Johanson left for Arizona in 1997.

“Ann and I met Garniss in the mid-1970s at Leakey meetings, and we became close friends and sometimes vacationed together,” said Gordon Getty. “I remember him at Machu Picchu a few years ago, hiking before we woke and spry as a mountain goat. A heck of a scientist, and a heck of a man.”

From volcanoes to radioactive dating

Curtis was born on May 27, 1919, in San Rafael, Calif. He was originally christened Chester Alphonse Kemp, but upon his parents’ divorce, his mother changed his name to Garniss Hearfield Kemp. He later took the surname Curtis after his stepfather. He obtained his B.Sc. in mining engineering from UC Berkeley in 1942. Following stints as a geologist for the Christmas Copper Corp. and Shell Oil Co., he returned to UC Berkeley to complete his Ph.D. in geology in 1951. He immediately joined the geology faculty.

Curtis initially focused on volcanoes and conducted seminal studies in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes in Alaska and in the Sutter Buttes in California’s Central Valley. He also helped delineate faults and evaluate earthquake hazard potential in the San Francisco Bay Area. His interest in the age of lava flows led him into radioactive dating.

He was admired for mentoring students as well.

“Garniss was supportive, a mentor and an all-around nice guy; a wonderful man who treated everybody well,” Dalrymple said.

Among his honors was the Newcomb Cleveland Award of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

According to his daughter Penelope Curtis, he was an avid hiker, birder and fly fisherman, and loved classical music, opera and accompanying friends to explore the geology of the mountainous areas of South America and Asia.

Curtis is survived by his brother Ralston Curtis, daughters Penelope Curtis of Grass Valley and Ann Pierpont Curtis of Orinda, son Robin Hearfield Curtis of San Rafael, Calif., seven grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. His wife of 45 years, Dorette Davis Curtis, died in 1987.

A memorial is planned for the spring. Donations in Curtis’s memory can be made to the Berkeley Geochronology Laboratory, the California Audubon Society or The Nature Conservancy.

* The original obituary incorrectly stated the date of Curtis’s death. He died the morning of Dec. 19, 2012.