#GlobalPOV: Art, videos and Twitter take poverty curriculum to the world

Three Cal alumni and teachers — a live-action sketch artist, a social-media proselytizer and a brilliant professor who is also an unapologetic Bono fan — have teamed up to create artful, provocative videos and brought Twitter into the classroom. The goal: to extend the teachings of Berkeley’s biggest minor, Global Poverty and Practice, online. The project could be a model for a new kind of public scholarship and online education.

April 8, 2013

Put a live-action sketch artist, a social-media proselytizer and a brilliant professor who is also an unapologetic Bono fan to work together, all Cal alumni, and what can they do about world poverty? The #GlobalPOV Project is what they’re calling it.

The three — professor of city and regional planning Ananya Roy; International and Area Studies lecturer and digital-media expert Tara Graham; and artist Abby VanMuijen — are creating artful, provocative online videos to crystallize the nuanced teachings of Berkeley’s biggest minor, Global Poverty and Practice, offered by the Blum Center for Developing Economies. And they are posting the videos online to extend the reach of the curriculum far beyond the classroom.

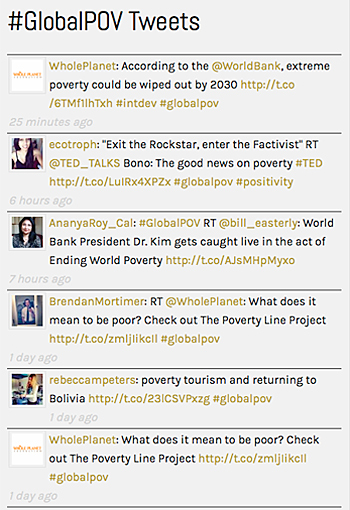

At Graham’s instigation, Roy also has harnessed Twitter, the world’s online living room for shorthand conversations on any topic, as a teaching tool. Using the hashtag #GlobalPOV, they’ve run a live Twitter feed in Roy’s global poverty class of more than 600, to give students a new way to speak up. And, between classes, Twitter has become a place where students, their professor and anyone else on campus or in the world who’s interested in poverty can exchange ideas.

Beyond that, the three, along with faculty in the GPP minor, are producing a book with UC Press that will pull together the approach and teachings of the GPP minor, complete with matrix barcode links to the videos.

The result is a multilayered, broadly accessible curriculum that they call critical thinking + improv art + new media.

The project is a groundbreaking alternative to dominant forms of online education, a hot topic that’s on the minds of campus leaders as well as the University of California as a whole, the state and educators everywhere.

“Our concern has been that most models of online education — stick a camera in a classroom and webcast it — don’t necessarily capture the most dynamic and inspiring and creative aspects of teaching and learning,” says Roy, a distinguished teaching award recipient who teaches the global poverty class in the minor. “So we started out with that puzzle and dilemma.”

While enhancing the classroom experience at Berkeley, the approach can be used anywhere, and it’s very flexible. An educator in a far-off classroom could show one of the videos and also use the clues and cues embedded in it to steer students to related films, books and papers. Someone just surfing the web who has an interest in the topic could watch the video and go from there. And scholars elsewhere could tune in via the Twitter conversation.

Any piece of the package can be useful on its own or can provide an entry point into a comprehensive and complex series of teachings on one of the world’s most intractable problems.

The concept got its start as a way to engage what Roy calls the “YouTube generation,” young “millennials” who grew up with the Internet and all its short, attention-grabbing content.

“It’s using YouTube as a platform to say ‘OK, can we have something interesting that sparks dialogue and critical thinking?’ ” explains Roy.

Making “something interesting” was key. The #GlobalPOV team very much sought to create something that would stand out from standard poverty-action videos.

“Most of them, I think, are really patronizing and oversimplify the very complex aspects of poverty action. They’re a call to action, but they don’t necessarily explore all the political and ethical issues that smart young people know are at stake,” says Roy. The minor addresses the complexities head-on — and so do the videos.

“Most of them, I think, are really patronizing and oversimplify the very complex aspects of poverty action. They’re a call to action, but they don’t necessarily explore all the political and ethical issues that smart young people know are at stake,” says Roy. The minor addresses the complexities head-on — and so do the videos.

The team discarded the classic memes of poverty-action videos, such as photos of poor-but-smiling children and lists of simple steps a viewer can take to “help.”

Like the minor, the videos are framed to encourage thinking about solutions to poverty that steer clear of what Roy sees as two extremes: “the hubris of benevolence, young Americans thinking ‘I’m going to solve poverty during my alternative spring break,’ and the paralysis of cynicism, which we have a lot of at Berkeley — really smart kids who know how to critique everything in the world but they’re not really sure what to do after that critique.”

With both the minor and the videos, she says, “We’re giving you a way to think about it, and you’re going to figure out your own piece of this.”

Each video starts with a question — for example, “Can we shop to end poverty?” — and offers a scholarly argument for a way of thinking about it.

To tell their story, the #GlobalPOV team put artist VanMuijen to work. As an undergraduate in urban studies (she graduated last spring), she developed a visual note-taking system that’s more drawing than writing, and she now teaches it to students all over campus.

Each video follows VanMuijen’s hand moving at lightning speed to sketch out key concepts: a grocery shopper at checkout, U2 star Bono’s (RED) campaign (he comes up in both videos so far), pockets stitched by “unskilled” workers. Between takes, VanMuijen and Graham cut and stitch pockets, bend wire into shopping carts, and otherwise improvise props they add into the action. The sketches are sped up, the props pop in and out, and what might have taken four hours to draw and fabricate races by in seconds.

The world is like a Rubik’s cube — we can hold it, change it, turn it, shake it, and solve it… but we must be taught the way, says the #GlobalPOV team: top to bottom, Abby VanMuijen, Tara Graham, Ananya Roy.

Visual note-taking helped VanMuijen absorb what she heard in lectures as a student. The notes she took in Roy’s global poverty class have been published as the “Global Poverty Coloring Book” for students now taking the class.

Producing the sketches for the video means that VanMuijen spends five to seven long days laboring in a dark room under a bright light, with a camera recording her every move. And that’s on top of long storyboard edit sessions with Graham. Editing, animation, sound and polish are added by Evolve Media of San Francisco.

Roy writes the script, with input from Graham and VanMuijen, and narrates. Her musical voice provokes as she leads viewers through film clips, information and questions.

The second #GlobalPOV video went live in early March, and within 48 hours of its debut, over 2,000 people had seen it. The number has now climbed steadily to more than 4,000. But Roy is more interested in longevity than in going viral, that each video holds up as a solid piece of scholarship.

“It’s like a book on a shelf, but it’s on YouTube,” she says.

Twitter, another piece of the package, was introduced as a way of increasing engagement within the classroom, making the professor more accessible to the students, and making it easier for students to take part without having to raise their hands in front of 600 of their peers.

It was Graham, director of digital-media projects at the Blum Center, who came up with the idea of using Twitter in Roy’s classroom last fall. Roy, who didn’t have a Twitter handle and has no use for Facebook, had to be talked into it — and is glad she was.

In the classroom, the live #GlobalPOV Twitter feed was projected behind Roy as she lectured. Insightful tweets found their way into her lecture, and Roy used the tweets to stimulate class discussion and write her post-class lecture supplements.

Professors and their scholarship can seem inaccessible, Graham says, but “when you move Ananya Roy onto Twitter and she’s retweeting you, she feels more accessible.” And her scholarship does too, Graham adds. The result: Students are more engaged.

“What Twitter did for celebrity culture,” says Graham, “we think it can do in the academic world by making professors and scholarship more accessible.”

#GlobalPOV is more work than any of the three imagined. “Really,” says Roy, “it would be so much easier for me to write a book.”

But the result, they say, is well worth the effort.

“There’s something about making one’s ideas accessible in this format that, to me, is quite important,” says Roy. “And I really think that’s partly what we must do as a public university: We have to invent new genres of public scholarship.”