Is antimatter anti-gravity?

Most physicists suspect that antimatter and normal matter weigh the same, that is, they are affected the same way by gravity. No direct measurements exist, however, that prove they do. UC Berkeley scientists, part of the ALPHA collaboration at CERN, are working on just such an experiment and have some very rough results.

April 30, 2013

Antimatter is strange stuff. It has the opposite electrical charge to matter and, when it meets its matter counterpart, the two annihilate in a flash of light.

Four University of California, Berkeley, physicists are now asking whether matter and antimatter are affected differently by gravity as well. Could antimatter fall upward – that is, exhibit anti-gravity – or fall downward at a different rate?

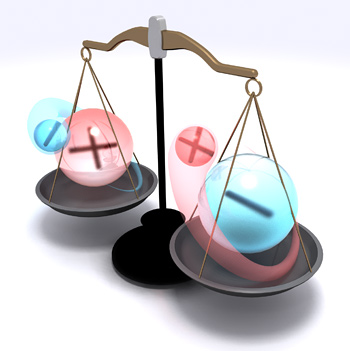

UC Berkeley physicists asked the question, does normal hydrogen (left, with a negatively charged electron orbiting a positively charged proton) weigh the same as antihydrogen (a positively charged positron orbiting a negatively charged antiproton)? Image by Chukman So, UC Berkeley.

Almost everyone, including the physicists, thinks that antimatter will likely fall at the same rate as normal matter, but no one has ever dropped antimatter to see if this is true, said Joel Fajans, UC Berkeley professor of physics.

And while there are many indirect indications that matter and antimatter weigh the same, they all rely on assumptions that might not be correct. A few theorists have argued that some cosmological conundrums, such as why there is more matter than antimatter in the universe, could be explained if antimatter did fall upward.

In a new paper published online on April 30 in Nature Communications, the UC Berkeley physicists and their colleagues with the ALPHA experiment at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Geneva, Switzerland, report the first direct measurement of gravity’s effect on antimatter, specifically antihydrogen in free fall. Though far from definitive – the uncertainty is about 100 times the expected measurement – the UC Berkeley experiment points the way toward a definitive answer to the fundamental question of whether matter falls up or down.

“This is the first word, not the last,” Fajans. “We’ve taken the first steps toward a direct experimental test of questions physicists and nonphysicists have been wondering about for more than 50 years. We certainly expect antimatter to fall down, but just maybe we will be surprised.”

Fajans and fellow physics professor Jonathan Wurtele employed data from the Antihydrogen Laser Physics Apparatus (ALPHA) at CERN. The experiment captures antiprotons and combines them with antielectons (positrons) to make antihydrogen atoms, which are stored and studied for a few seconds in a magnetic trap. Afterward, however, the trap is turned off and the atoms fall out. The two researchers realized that by analyzing how antihydrogen fell out of the trap, they could determine if gravity pulled on antihydrogen differently than on hydrogen.

Antihydrogen did not behave weirdly, so they calculated that it cannot be more than 110 times heavier than hydrogen. If antimatter is anti-gravity – and they cannot rule it out – it doesn’t accelerate upward with more than 65 Gs.

“We need to do better, and we hope to do so in the next few years,” Wurtele said. ALPHA is being upgraded and should provide more precise data once the experiment reopens in 2014.

The paper was coauthored by other members of the ALPHA team, including UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow Andre Zhmoginov and lecturer Andrew Charman.

MORE INFORMATION

- Description and first application of a new technique to measure the gravitational mass of antihydrogen (Nature Communications)

- ALPHA experiment at CERN

- To read more about the ALPHA experiment, see Jun. 5, 2011, press release: CERN group traps antihydrogen for more than 16 minutes