What’s the matter with sports fans?

Author, J-School instructor and sports nut Eric Simons set out on a quest to figure out why he, and millions of other fans all over the world, act the way they do. He gathered his findings in a new book, The Secret Lives of Sports Fans.

May 13, 2013

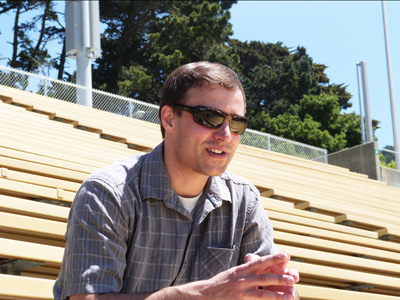

Eric Simons sits 50 rows up in Memorial Stadium, under a clear blue sky and a golden sun, reliving what he calls “this awful moment in Cal history.”

It was from this very spot — section TT, straddling the 20-yard line, where his Berkeley-alum father has held four season tickets for the past 30 years — that Simons witnessed the end of the world on the night of Oct. 13, 2007, when a brain cramp by a freshman Golden Bears quarterback led to a heartbreaking last-second loss to Oregon State, costing Cal its best shot at a Rose Bowl berth since 1959.

Simons revisits an “awful moment in Cal history” from section TT, his accustomed spot in Memorial Stadium. (Barry Bergman/NewsCenter photos)

“I remember Kevin Riley coming this way and then running that way,” says Simons, now a lecturer at the Graduate School of Journalism. “Everybody’s standing, and you can feel 75,000 people thinking, ‘Throw the ball away.’ And he did not. And everybody starts to gasp. And I remember the clock running down, you could see it hitting zero, and Jeff Tedford was probably standing over here, off my left shoulder, and the student section over here was noisy, and then just silent.

“I remember standing here with my hands on my head, and everybody else standing with their hands on their heads, and I remember Tedford throwing his headset. And then the BART ride home, when I remember feeling so isolated because I was sweaty and disgusting and exhausted, and my hat for whatever reason had shrunk and my head felt like it was pulsing through the hat. And I was kind of like, ‘What is wrong with me?’ In that moment, so much happened to me.”

To the Berkeley J-School grad, a science journalist as enamored of great white sharks and hammerheads as of his beloved hockey Sharks, this was not a rhetorical question. What did happen to Simons — and what happens to anyone for whom love, hate, ecstasy, despair, personal relationships and personal hygiene can hinge on the fortunes of strangers performing spectacular feats with balls or pucks or only their own bodies — is the subject of his second book, The Secret Lives of Sports Fans: The Science of Sports Obsession.

“The book is really trying to unpack what’s happening in that moment, but then realizing that part of the limitation of science is that it can’t possibly definitively capture its complexity,” says Simon, who sought answers everywhere from labs to watering holes, where he picked the brains of experts in testosterone, mirror neurons, philosophy, psychology, culture and Cleveland, among other subjects with something to tell us about sports fandom. The book explores the joy fans take in the success of their favorite teams and athletes — and that many take from the failure of rivals — and the peculiarly close connection some feel with perennial losers. (See “Cleveland,” above.)

So are sports fans empaths? Sociopaths? Junkies? Lovers? Haters? Testosterone freaks? Tribalists? Armchair warriors? Pseudo-religionists? Why is wearing the wrong colors at a soccer match in Italy or Argentina, say, an invitation to mayhem, while a Cardinal jersey in Berkeley on the day of the Big Game is apt to draw mostly good-natured ribbing?

And are the answers likely to be found in biology and chemistry, or in disciplines like sociology, psychology and cultural anthropology?

Sports fans are people, too

Actually, Simons believes, it may be all of the above. Sports fans, it seems, contain multitudes.

“There’s not very much that’s simple about it, even though it looks so simple, right?” he says. “I mean you’re just standing here, looking like a moron. Or you’re sitting on your couch, becoming part of the furniture, and everybody’s looking at you like, gee, you haven’t moved in four hours.

“Cognitively you look like you’re shutting down,” he says, “but actually you’re going nuts.”

On the strength of three years of research for the book, Simons thinks psychologists and neuroscientists, among others, tend to underestimate the complexity of sports fans. In the developing field of mirror neurons, for example — which he invokes to help explain why “my brain leaped out of my skull” as he anticipated, from the relative comfort of his own couch, a punishing fourth-overtime loss endured by his upper-case Sharks — available money and technology are being applied, understandably, to the study of “more important stuff” like autism, addiction and language.

“So they have an excuse,” allows Simon, managing to keep his passion in perspective, just as he counsels his fellow fans. “But people who study group psychology – it’s kind of amazing that nobody really looks at the big, obvious tribalism in American society, group perception and bias,” and other attitudes and behaviors he sees as directly related to being a fan.

“So they have an excuse,” allows Simon, managing to keep his passion in perspective, just as he counsels his fellow fans. “But people who study group psychology – it’s kind of amazing that nobody really looks at the big, obvious tribalism in American society, group perception and bias,” and other attitudes and behaviors he sees as directly related to being a fan.

“I talked to a lot of psychologists who really, fundamentally do not understand sports fans and have no desire to understand sports fans, trying to convince them that I think their work describes what’s happening in my head,” he says.

Then again, he concedes, the insides of fans’ heads may not be that different from those of anyone engaged in politics, say, or other fiercely competitive enterprises.

“I don’t distinguish sports fans that much anymore from the rest of humanity,” he says. “A lot of things that you see that you ascribe to their being sports fans — it’s really just that they’re people.”

Regardless of the convolutions that drive otherwise sensible people to fandom — all that crazy cross-talk between hormones, mirror neurons, memory, identity and culture — it’s up to them whether they turn into violent football hooligans or fun-loving Bears fans, Simons contends.

“What I want to say to all sports fans is, ‘You have a lot of stuff that you have the capacity to do, but that doesn’t mean you have to do it, or should do it,'” he says. “Which is what most evolutionary biologists say. There are a lot of ways we’re set up to behave, but that doesn’t mean you have to behave that way.”

But why some do, and others don’t, remains for Simon an unsolved mystery of science. He hopes his book will help to prod further research.

“Part of the fun of the book is saying, Here’s this really amazing way that we behave, and it looks like all these other ways that we behave,” he explains. “Wouldn’t it be cool if we could figure out more about this, and answer some of these questions?”

Just the same, “I feel like I’ve satisfied myself about a lot of the ways I act,” says Simons, looking down on the spot where, nearly six years ago, a freshman holding a football triggered a collective meltdown among thousands of Golden Bear fans, from rowdy undergrads to gray-haired scholars who’ve devoted much of their working lives to studying “more important stuff.”

“I think about it a lot,” he adds, “just because I’m here a lot. I sit in this seat a lot, and a football game is four hours long, which gives me plenty of time to consider, ‘Why am I acting the way I’m acting right now?'”

On this placid spring day, 50 rows up in a nearly empty stadium, he seems perfectly normal.