Century-old ham radio club making waves in Richmond

With one new station built and another on the way, UC Berkeley's century-old Amateur Radio Club is celebrating its past by revving up for its future.

February 24, 2014

The Bay Area might be a hotbed of high technology, but low technology has its fans, too. Just ask the UC Berkeley Amateur Radio Club. It’s been around 100 years, and its members don’t mind a little dust and rust on their tech.

“I think the old equipment is really cool and retro,” says club member and electrical-engineering major Andy Hu.

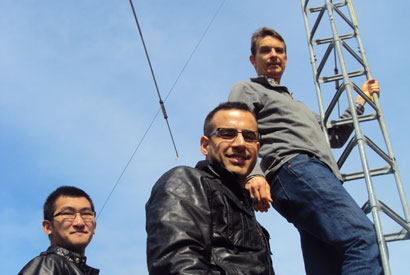

Andy Hu (left) and Tholfaqar Mardan (center) with faculty adviser Friedrich Sommer beside the club’s antenna tower at the Richmond Field Station. (NewsCenter photo by Steve Hockensmith)

“I’m still fascinated by the profundity that an electrical signal can leave the radio in front of me, travel up a wire to an antenna outside, and someone halfway around the world with an antenna outside connected to their radio can hear my voice and talk with me,” says club member Bill Mitchell, a chemistry graduate student.

Often called “ham radio,” amateur radio is the recreational or experimental use of radio frequencies set aside for non-commercial purposes. The field was still in its infancy in February 1914, when an amateur radio club and station were founded on campus. Though that original station is long gone, a new one was established at Berkeley’s Richmond Field Station last year, and yet another is being set up in Cory Hall and should become operational this spring.

The club will commemorate its centennial this week by hosting an exam for people wishing to get an amateur radio license — more people, it turned out, than the club could accommodate this time around. (No license is required to monitor ham transmissions, but anyone who wants to broadcast or work on amateur radio equipment needs to be licensed by the FCC.)

Though the club currently has 25 members — mostly undergrads, with some grad students and staff and faculty members mixed in — there have been times when it had none. Off and on over the years, the club has lain dormant. That was the case when Friedrich Sommer came to Berkeley in 2005.

“I grew up in Germany in the ’60s and ’70s, and for me amateur radio was the window to the world, even across the Iron Curtain,” says Sommer, an adjunct professor at the campus’s Redwood Center for Theoretical Neuroscience and the club’s faculty adviser. “But when I arrived at Berkeley, the club was entirely inactive. There was no equipment, no spot where people could meet and put up antennas, nothing.”

That started to change after the club was contacted by Stephen Stoll, then the head of the campus’s Office of Emergency Preparedness, who was interested in ham radio’s potential usefulness during a crisis. While the Internet and telephone service are both vulnerable in times of emergency, the broad, decentralized networks of amateur radio operators are harder to knock out. That’s why emergency preparedness is a major part of the club’s charter.

With Stoll’s help, the club got its new home base at the Richmond Field Station. What was once a disused shack is now filled with amateur radio equipment both old and new, and club members erected a 25-foot-high antenna tower that allows it to communicate with fellow ham enthusiasts thousands of miles away. On a typical day, the station picks up Morse code signals and voice broadcasts from as far off as Antarctica. Sommer says the club can use its space at the field station to do “outlandish stuff,” such as setting up a large mirror that will allow members to bounce radio signals off the moon.

Much of the equipment was donated by Bay Area ham operators over the last few years, and the club has enough radio transmitters and receivers for its collection to qualify as a mini amateur radio museum.

“What we have here is basically a walk through history,” says Sommer. “We have equipment from as far back as the 1930s that you can still actually use. So part of the club’s mission is to give people direct access to this old, beautiful technology.”

That direct access is what drew Tholfaqar Mardan to the Amateur Radio Club. A programmer/analyst in the Department of Mechanical Engineering’s computer mechanics lab, Mardan says he enjoys the clubs activities and outings, such as the day it spent broadcasting from the bridge of a soon-to-be-mothballed battleship, the U.S.S. Iowa. But it’s what he calls his “passion” — building radio circuits — that makes the club a perfect fit for him.

“It’s the club for experiments, building stuff and meeting like-minded people,” says Mardan, who jokes that he especially appreciates the opportunity to “borrow expensive, high-power radio equipment for free.”

“A big attraction to this club is the hands-on and modular aspect of the equipment,” adds Hu. “With the integrated-circuit devices we have today, it can be difficult to take something apart and learn from it.”

That’s why Michael Lustig, an assistant professor in the Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences department, has started teaching his students about amateur radio. Lustig says there’s plenty that a 21st-century electrical engineer can learn from tinkering with 20th-century amateur radio technology.

“It involves using radios and electronic equipment and knowing electromagnetics, so there are a lot of aspects that we as electrical engineers actually use in real life,” says Lustig, an Amateur Radio Club member. “With something like cellphones, the technology is mostly hidden from us. With a ham radio, you can actually see and have access to the technology. Even though it’s older, it’s still the same basics.”

Not only has Lustig gotten his amateur radio technician’s license, he’s having the students in his digital signal processing class go for theirs, too. All 60 are expected to take the Amateur Radio Club’s license exam.

Sommer hopes some of those newly licensed amateur radio technicians will join the club. According to him, young people with an affinity for the popular, do-it-yourself-oriented ethic known as “maker culture” might already be coming to ham radio in greater numbers: There are approximately 714,000 FCC-licensed amateur radio operators today, up from around 655,000 seven years ago.

“For some time, the attitude seemed to be, ‘Oh, that’s old-fashioned stuff. We don’t need that anymore,'” he says. “So it’s very interesting to see that the interest has really revived and people are recognizing that there’s a benefit to directly working with and experimenting with this hardware.”