University Librarian reflects on a transformative era

Tom Leonard, who has led UC Berkeley's Library for 14 years, plans to retire in June 2015. He reflects on the Library and his years there — touching on transformative technology, budget challenges, mass digitization, fair-use issues and student sit-ins and "nude run" — in a NewsCenter Q&A.

July 29, 2014

With no experience as a librarian but a track record as a skilled administrator at the Graduate School of Journalism, Tom Leonard was appointed University Librarian in 2000. He plans to retire next June after what will be a 15-year tenure heading Doe, Moffitt and Bancroft libraries and more than a dozen subject-specialty collections spread across the campus (together referred to as “the Library”).

Leonard has guided the Library through a transformative era — one that has seen major cuts in state funding and the mass digitization of more than 3.5 million volumes held by UC libraries. From his large corner office facing the Campanile esplanade, he spoke recently with the NewsCenter about his tenure at the Library and what lies ahead.

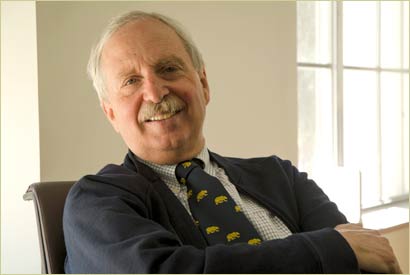

University Librarian Tom Leonard (Cathy Cockrell/NewsCenter photo)

What was your early experience with libraries?

My mother was a librarian in a public library outside Detroit and often brought me to work with her. I grew up seeing card-catalogue cards being typed and books being checked out. I also remember, as a young person interested in political change, that the library provided a meeting place to talk to people. It stuck with me that libraries are important places.

Do you recall your first encounter with the library and collections here at Berkeley?

I remember walking in through the north entrance to Doe one afternoon in 1967 and going to the Humanities Graduate Services. I don’t think I had my student ID yet, but the librarian was very nice and let me take a look. I ended up spending a lot of hours there doing research for my Ph.D. in history.

You became University Librarian right around the turn of the 21st century. What was the outlook for the Library at that time?

The campus had a compact with the governor for new funding, but a lot of the money pledged never materialized; the state’s initial commitments fell victim to California politics and the downturn in the state economy. The recession, starting around 2008, led to cuts of as much as 25 percent to the Library’s operational budget. So we have to be more active with the donors, foundations, other parties in higher education.

What were your priorities in guiding the Library through lean times?

We created incentive programs for things like time reduction and early retirement — trying to be very resourceful so that we would not have a library that was beset by layoffs. With layoffs, because of bumping and seniority rules, we would have lost the people most recently hired — some with the advanced technology skills able to take a library into the 21st century.

Do you count that transition among your biggest accomplishments?

Doe Library’s Heyns Reading Room, home to thousands of periodicals (Steve McConnell photo)

Yes. Our great research libraries were about housing or shelving millions of books, which made sense through much of the 20th century. But we have so many other ways of delivering information these days. So we needed to take advantage of new tools as well as to redesign and redeploy library spaces.

We still have our heritage spaces such as the North Reading Room (where we’ve preserved the original 1912 look and feel but added power supply and Wi-Fi). But you’ll now find lots of places in our libraries that are more flexible and sometimes louder and more active, in light of new ways that students are learning.

Have you always been enthusiastic about mass digitization of library materials?

Yes. Some would say too enthusiastic. Because I know what it’s like to face a long row of books and pull them out one by one to search the index for clues to what’s inside. It was transformative when library materials could be searched electronically. That’s happened in a relatively short period of time because the great research libraries threw some caution to the wind and digitized their material.

Predictably, we were sued by some publishers and authors for doing that. I think that was a very misguided effort to slow down an inevitable transformation — namely the indexing of what’s between the covers of the millions of books in our heritage collection; I’m not talking about full display of people’s work.

It’s a great achievement that we’ve opened up our collections using digital tools. I’ve had lots of authors look at me like I’m a devil, but I’m happy to bear the criticism. Making our great collections visible and discoverable is worth every bad hour.

What’s a bad day at the Library?

Any organization that has roughly 500 students and 400 career staff generates HR headaches, and some of them reach my desk. Also, any time someone does something wrong in one of our facilities, I’m likely to learn about it. There’s a whole catalog of troubles that a bunch of 18- to 21-year olds can get themselves into when they’re in the library.

And a good day?

I’ve had many great days. It’s not unusual to get a note: “I’m studying x. I know it’s a really obscure topic, but this librarian was a real genius…” I get to open a lot of Valentines to the Library and our staff.

What did not go wrong on your watch that you expected would be a headache?

I inherited the nude run in the Gardner Stacks during finals. It’s entirely student governed, and although it offers plenty of potential for embarrassment for the Library, we’ve gotten not a single complaint.

I would not say that a sit-in or an occupation means a bad day. Since 1967 I’ve seen enough Berkeley demonstrations and protests that they seem part of the texture of the place, rather than signs of something deranged or wrong. It’s likely in our society, with the kinds of problems people confront, that they are going to demonstrate the way they feel and do so in cultural institutions like libraries.

In fact you had a cameo in the recent documentary “At Berkeley,” during a student protest in the Library.

“I would not say that a sit-in or an occupation means a bad day,” says Leonard, pictured here as students occupy Doe’s North Reading Room in 2010. (Steve McConnell/NewsCenter photo)

That’s right. It’s quite typical for librarians to be very calm and conscientious in such situations. Librarians do want as much control and order as possible, but UC Berkeley librarians are not fazed by much.

Is there anything you’ve been dead wrong about at the Library?

Our bronze bench with a life-sized Mark Twain sitting on it, reading Huckleberry Finn. At first some of us didn’t have the wit to realize this would be a magnet and a great way to get people thinking about literature. In fact the sculpture is much beloved. Families and students from abroad, in particular, like to pose next to the author.

Any advice for your successor?

This is not a place where a dean or leader can be primarily away from the scene, raising money or writing books. At Berkeley you have a much greater chance at success if you are visible and active with your campus partners and know your people well. Having knowledge of intellectual-property issues, or a great capacity to learn and be active in that arena, is also advisable.

I take it your concerns around intellectual property and fair use led to your recent involvement in the Authors Alliance.

Leonard penned works on the Armenian genocide and the alleged ax murderer Lizzie Borden, as well as this prize-winning New Yorker caption while focusing on the Library. “My interests haven’t narrowed as I learned library speak,” he says.

Yes. I’m concerned with what happens to published work that is “orphaned” — left in the stacks with no chance of being fully digitized because of our creaky copyright laws. With three other Berkeley faculty I helped start Authors Alliance, which represents writers who know how helpful it is to stand on the shoulders of other scholars by having access to their work. We are encouraging those who share our passion for moving work that has outlived its commercial life into the public domain.

The Library spends more than $5 million a year to license materials, so that students, faculty and staff can see all of this material from their home. But I also try to keep in mind the independent scholar who doesn’t have an affiliation with a research university. That researcher is a second-class citizen when it comes to information. Libraries should work to end that.

Is the Alliance something you plan to continue working on after you leave next summer?

That’s one of the projects I’ll devote more time to. And I am a writer, with projects that I’ve put on the shelf. I might even write about the First World War; we’re in its centennial years, so that’s an attraction.

Related information:

- Parricide on the QT: Notoriety and knowingness at the dawn of new media (Tom Leonard’s paper on Lizzie Borden)

- One librarian. Eight words. One big win in New Yorker cartoon caption contest (NewsCenter article)

- Commission on the Future of the Library issues its report (NewsCenter article, October 2013)

- Four Berkeley professors launch new nonprofit to advance the publishing rights of authors in the digital age (College of Letters and Science article)

- As students embrace new ways to learn, library learns to adapt (NewsCenter article, March 2014)