Troy Duster’s garden of plugged-in scholarship, and how it grew

During a day of thanks and tributes, former students and lifelong friends lauded the Berkeley sociologist for a 40-year career marked by prescient insights, generosity of spirit, twinkly activism and far-reaching influence.

August 20, 2014

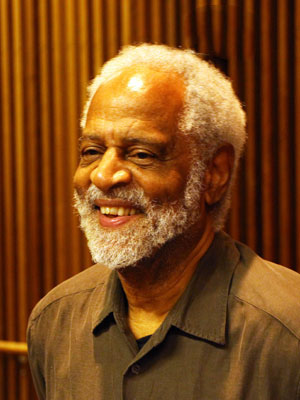

Troy Duster (UC Berkeley photos by Barry Bergman)

“I once had a very good professor who gave me very bad advice,” UC Berkeley sociologist Troy Duster said Friday, standing behind a lectern at Booth Auditorium. “‘Don’t read newspapers. Don’t listen to the news. It’s simply a daily phenomenon that will get in the way of scholarship.’”

The young graduate student ignored the advice, rejecting “this notion that one celebrates the scholar who is disengaged from the world, that the high-status theorist — whether in anthropology, sociology, political science — was one who wasn’t immersed in the daily turmoil of life, but had almost an ivory-tower rendering of self.”

Duster, in fact, went on to become the epitome of the engaged scholar — writing landmark works on the racial implications of drug policies and genetic research, founding what is now the campus’s Institute for the Study of Societal Issues and mentoring scores of doctoral students who would themselves become leaders in the fields of public health, law and public policy, education, medical anthropology and theory of social inequality and social change.

So it was fitting that during a buoyant day of thanks and tributes, what was celebrated was Duster’s plugged-in, hyper-engaged approach to scholarship — including what Stanford medical anthropologist Duana Fullwiley, a Berkeley Ph.D., called “his solid support, his integrity, his centered vision, his friendship, his lightheartedness, his poetic style of reasoned advice and his stories.” The daylong appreciation featured a sampling of former students, fondly known as “Troy’s babies,” and such luminaries as U.S. District Court Judge Thelton Henderson, Oakland Children’s Hospital chief Bertram Lubin and restaurateur and food activist Alice Waters, owner of Chez Panisse.

It was a day of laughter, tears, sociological insights and paeans to Duster’s “prescience,” generosity and friendship. There was even a Bach selection from a cellist invited to perform by Berkeley alum Tania Simoncelli, an assistant director for forensic science at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. A cellist herself, she originally connected with Duster, a fellow music lover, “over our shared passion for the intersections of science and biomedicine, and ethics and justice.”

Duster later said the tributes made him “a bit uncomfortable,” though discomfort, by all accounts, is not a particularly “Dusterian” trait. Sounding a refrain picked up by a number of speakers, Harry Levine, another Berkeley Ph.D. and a Queens College sociology professor, dubbed him “the coolest cat in the room.”

Code-switcher, seed-planter

In 2004, when Duster was named president of the American Sociological Association, Levine — who studies the disproportionate impacts of arrests for marijuana possession on young blacks and Latinos — attributed Duster’s far-reaching influence to his being “a code-switcher,” a man who is “culturally multilingual.”

Sandra Smith

“He can talk to white audiences about racism and the need for affirmative action, to administrators about student needs, to geneticists about how society works and to sociologists about how genes work,” wrote Levine.

“Duster,” he wrote, “also seems able to see around corners and three or four chess moves ahead of ordinary mortals.”

Howard Pinderhughes, an associate professor in health and behavioral social sciences at UCSF, recalled his own days as a struggling grad student, when Duster brought him into what was then the Institute for the Study of Social Change, offering him a sense of community, a source of income and a guiding hand in shaping his academic career.

“For me and many others, Troy’s legacy goes beyond the scholarship and theory that he produced,” said Pinderhughes. “It was the way he seeded the intellectual universe with pods and seeds of insurrection, contestation and social change.”

“I don’t think I’ve ever heard Troy raise his voice,” he added. “You are one of the few people I know who can convey outrage, and people walk away feeling very good about it.”

Sandra Smith, a Berkeley associate professor in sociology, came to know Duster as an assistant professor at New York University, where he began teaching in 1999. She remembered how they happened to be standing together at Washington Square Park on Sept. 11, 2001, watching in horror as the first of the World Trade Center’s twin towers fell.

But she also recalled how Duster helped her through her personal struggles after moving west and joining the Berkeley faculty.

“I think everyone in this room would agree we are are hardly in a postracial America,” Smith said. “There is still much more to be done, both on this campus, in my department, in the larger society. What goals do we have and how are we going to achieve them? One of the things I respect so much about Troy is that he keeps pushing these agendas. And he does it with a kind of twinkle in his eye.

“He’s a fierce kind of activist,” said Smith, “but one who always ends a sentence with a smile, so you can’t help but be challenged by him, but also adore him.”

Spheres of influence

The grandson of legendary journalist and civil-rights activist Ida B. Wells, Duster made his mark with his first book, The Legislation of Morality — published in 1970, the year he joined the Berkeley faculty — an investigation into the ways that drug use morphed from a health problem to a criminal one as addiction spread to the inner city. Two decades later, in Backdoor to Eugenics, he set the terms of an ongoing debate over the influence of social and political values in genetic research and “pure” biological science.

Alice Waters

In 1979 he founded ISSI’s forerunner, the Institute for the Study of Social Change, and was its director for 18 years. A Chancellor’s Professor and senior fellow at Berkeley’s Warren Institute on Law and Policy, he sat on the board of the Association of American Colleges and Universities from 1997 to 2003, and has served on academic and public-policy panels ranging from the President’s Commission on Mental Health to the National Advisory Council for the Human Genome Project.

And while he has “almost retired from teaching,” Fullwiley said, “his legacy and influence will live on.”

Henderson — a Berkeley alum whose name now graces the law school’s Thelton E. Henderson Center for Social Justice — recounted how in 1998, on the day he turned 65, he stopped hearing criminal cases as a protest against mandatory sentencing guidelines for crack cocaine users, “a bit of legislated morality that reeked to me of bias and unfairness.”

That decision, he explained Friday, had its roots in his intellectual and personal relationship with Duster, his friend of nearly 50 years, whose 1970 insights into the racial underpinnings of drug policy were “a revelation to me.”

In the mid-’90s, when Alice Waters first got the idea for her Edible Schoolyard project — an organic garden and “kitchen classroom” she launched at Berkeley’s Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School — Duster was “the first person I called,” she said, “because I wanted to know that he thought it was a good idea.”

He did, thus adding the sustainable-food movement to his manifold spheres of influence.

In his own brief remarks at the end of the day, Duster recalled a scene from the 1982 film The Year of Living Dangerously. Two characters, journalists in Indonesia in the 1960s, argue the merits of giving money to the poor versus addressing larger, structural issues.

“It turns out that both things are true,” Duster said. “You can meet people on the street — or at a university — and you can, on a one-on-one, individual basis, have a fairly important impact with, metaphorically, a few coins.

“You don’t know that when you’re in the experience,” he added. “You only know it 40 years later, when they have some kind of celebration for you.”