A splendid esplanade: major overhaul for Campanile’s grounds

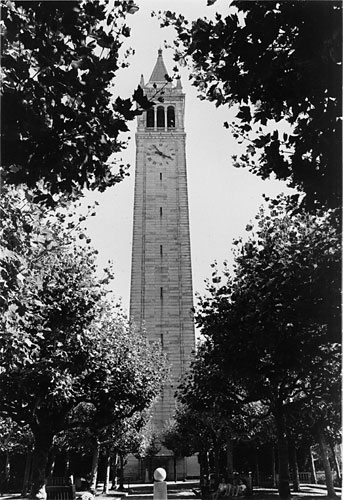

The Campanile's 100th birthday is in 2015, and its historic esplanade – the terraces, trees, lawns and staircases surrounding the tower – got a summer spiff-up for the celebration.

September 2, 2014

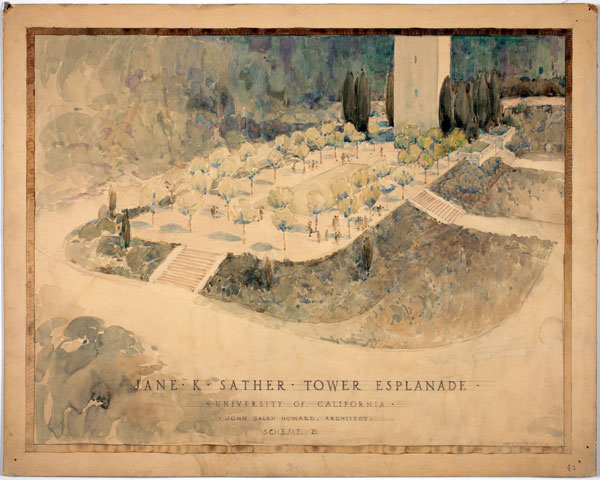

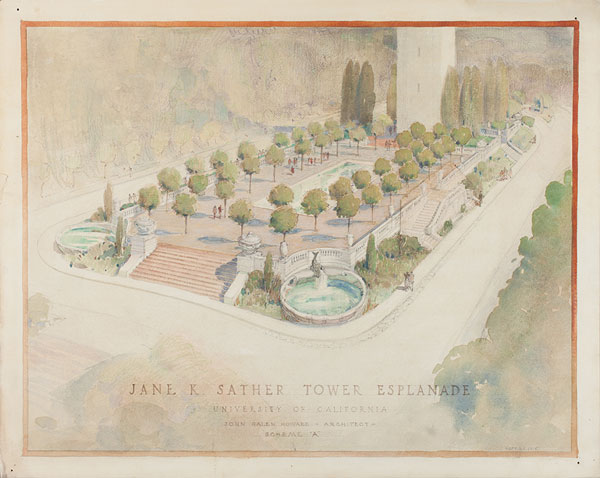

The Campanile’s 100th birthday is in 2015, and its historic esplanade – the terraces, trees, lawns and staircases surrounding the tower – got a summer spiff-up for the celebration. Nearly the same age as the tower, the open, level walkway was designed by campus architect John Galen Howard in the early 1900s to be an elegant main hub for students to meet. Construction on it began as the Campanile was being finished.

Few repairs ever have been done to most of the outdoor space, so the update was long overdue, says Jim Horner, UC Berkeley’s campus landscape architect. The work, paid for with funding from Capital Renewal, a campus program that helps restore and repair facilities and grounds, kept the site’s original character intact, since, like the Campanile itself, the esplanade is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Over the years, the esplanade became a quiet, contemplative spot. But it has also been a popular venue for special events, including graduation receptions, milestone birthday parties for Chez Panisse and Nobelist Steven Chu, class reunions, wedding receptions, Charter Day lunches, an annual charity egg hunt and – since at least the 1940s – midnight Cal song fests held prior to home football games.

To Horner, the esplanade is “a sacred landscape space at UC Berkeley” because of its historic significance and its survival without change over so many years. A 1978 campus historic resources study called both the Campanile and the esplanade a “central campus shrine.”

“Most landscapes grow and change in form,” Horner explains, “but the esplanade has been a set piece now for 100 years. It’s quite wonderful to get it ready for the next 100.”

Brick-by-brick renovation

General Contractor: Vila Construction

Landscape Architect: RHAA Landscape Architects

Project Management: UC Berkeley Capital Projects

Just north of the tower, the aging decorative brick and asphalt paving was pulled up completely in June. This was done primarily because the redwood headers surrounding the bricks had splintered and rotted, and as a result, the paths became uneven and a source of ponding and tripping hazards.

But before they were removed, many of the uncounted thousands of bricks in the 8,750-square-foot area – those used to form edges and circles and more complex designs – were numbered and their exact placements in the ground photographed. “It’s a huge jigsaw puzzle, if you think about it,” Horner said earlier this summer, watching a work crew begin putting bricks back into their historic patterns.

Beneath the bricks – each inscribed on its underside with the word “California,” for the former California Brick Company – at least three inches of crushed rock was added for support and help with drainage, then a layer of filter fabric, and finally a new bed of sand. This technique is being used elsewhere on campus to try to keep more rainwater onsite, where it falls, so it can be absorbed into the soil instead of running into drains or pooling.

The deteriorated redwood headers were replaced with three-inch-wide strips of granite – the same Sierra White granite from a Madera County quarry that was used to cover the 300-plus-foot-tall tower’s exterior walls, and many other campus buildings of that era.

Missing sea creature’s return

In the middle of the esplanade, a missing piece of the Mitchell Fountain – a 109-year-old granite pillar with a drinking fountain on one side – also has been restored. The fountainhead, in the shape of a sea creature, had been missing at least since the 1970s and was recreated earlier this month by artist Tom Shray at Mussi Artworks Foundry in Berkeley, with guidance from photos in the University Archives.

Campus planning specialist Steven Finacom “did the research that unearthed the imagery that provided our only clues to what this ornament looked like,” says Horner. Although it won’t produce drinking water today, the creature once offered it to passersby who pinched its ears, and excess water ran into a bronze clamshell bowl below.

That memorial. another of architect Howard’s designs, honors John Mitchell, a retired soldier and 1874 Congressional Medal of Honor recipient. Between 1895 and 1904, Mitchell was the campus armorer, responsible for maintaining the University Cadets’ practice weapons and locker rooms, and he was popular with cadets for his U.S. Army tales. At the time, military training for young men was a mandatory part of state land grant college curricula.

The esplanade is a sacred landscape space at UC Berkeley.

– Jim Horner, campus landscape architect

The cadets raised money for a memorial to Mitchell after his death, and the monument was placed between North Hall and Bacon Hall – likely a bit south of its current location – on May 5, 1905, and then moved to its current location when the esplanade opened 10 years later. Finacom thinks the choice of adding a drinking fountain there was not only to provide a memorial, but also a practical resource for cadets who endured often hot and dusty marching drills on that part of the campus each day at 11 a.m.

The granite orb atop the pillar, or obelisk, is considered by some to represent a huge cannonball, but it’s also more recently been known as “the 4.0 ball,” which students rub for good luck before finals.

Visitors to the esplanade can relax around the fountain in four oversized Honduran mahogany benches paid for by the Class of 2002 as memorials to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and refinished as part of the renovation. Each durable bench is inscribed with a different message, including “Remember 9/11” and “Pause and Reflect.” The benches previously on the site had deteriorated and were removed in the 1980s, and new ones were built in the original style.

President cleaned up, plane trees checked

The esplanade’s sundial – an anniversary gift of the Class of 1877 given to the campus about the time the Campanile was completed – and, at the tower’s entrance, the stone Class of 1920 bench, a World War I memorial with sculptures of two “mourning bears,” needed few, if any, fixes. But the same was not true of the bronze bust of Abraham Lincoln presented to the university in 1909 and installed in 1921 on the base of the tower’s south façade. Made by artist and sculptor Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum, who created the monumental presidents’ heads at Mount Rushmore, the very tarnished bust was cleaned up earlier this year.

A gift to the university by former student Eugene Meyer, it is a replica of a marble bust of Lincoln that Meyer gave to the U.S. Capitol. Meyer became owner of the Washington Post and the father of Katharine Graham, who began leading the Post in the ‘60s.

Each of the esplanade’s 54 iconic London plane trees was inspected this summer by an arborist as part of the renovation project, and all but a few are in good shape, despite their age, Horner says. The sycamore hybrids were geometrically planted in a grid pattern after being shipped across the bay in 1915 from San Francisco’s just-closed Panama-Pacific Exhibition, a world’s fair held in the city between Feb. 20 and Dec. 4, 1915.

Distinctive for its new growth being pollarded, or pruned back, to the knobby ends of the main branches each year, the plane tree became an iconic landscape element on the campus and was replicated over the years in at least five other locations, including Campanile Way and Sproul Plaza.

Something old gets something new

The esplanade project added two features to the space that weren’t part of history. The first is a granite stepping stone pathway across the grass in the southeast corner, where pedestrians had worn a diagonal shortcut. “We decided to not to fight this, but to formalize it,” says Horner. “This will allow people to continue to walk where they have been across that lawn panel.”

Also new are plantings of white roses and low shrubs at the base of the Campanile and around the 12 red cedar trees that stand beyond the corners of the tower. Horner put a Japanese maple in a landscaped alcove south of the tower.

Earlier work in the area made the entrance to the Campanile lobby accessible for the first time to wheelchairs.

A new granite bench installed near the sundial will provide “a place to sit and look at Stephens Hall” and feel the specialness of the almost century-old Campanile and the grounds surrounding it, says Horner. Like the Campanile and its esplanade, Stephens Hall was designed by Howard; its grand memorial room on the top floor is symmetrically on axis with the tower.

As a Berkeley student, Colleen Rovetti, now the campus’s executive director of external relations and chief of protocol, escaped to the esplanade for solace. She looks forward to enjoying the view and the renovated space.

“I have always been drawn to the esplanade – it’s a hidden gem,” she says. “You often can go up there and find it nearly empty, right in the heart of campus. I used to pretend it was all mine.”