Where T-shirt culture meets the black protest tradition

For her dissertation research on T-shirts and the black-protest tradition, doctoral candidate Kimberly McNair has been known to visit street fairs and flea markets — to find new Ts and meet their vendors — as well as to read scholarly theory on performance, media and "remix" practices.

September 8, 2014

Just about everyone owns a T-shirt, “even the Queen of England,” says Berkeley graduate student Kimberly McNair.

A doctoral candidate in African diaspora studies with a focus on popular culture, McNair takes a scholarly interest in this ubiquitous and democratic article of clothing. For her dissertation research on T-shirts and the black-protest tradition, she’s been known to visit street fairs and flea markets to find new Ts and meet their vendors, as well as to read scholarly theory on performance, media and “remix” practices.

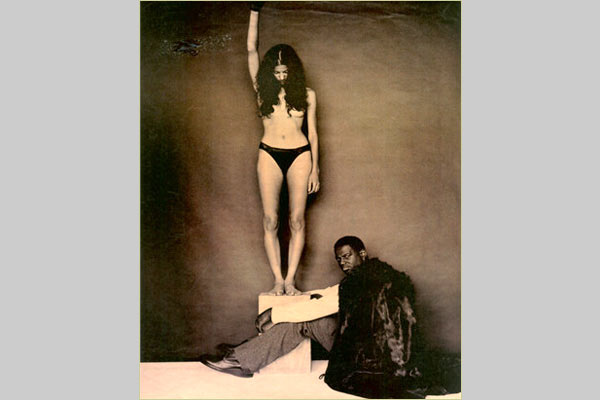

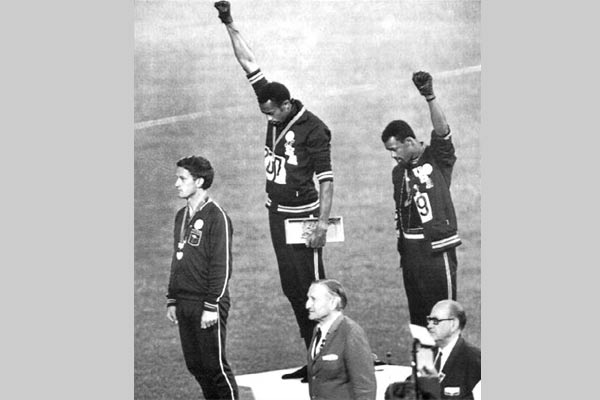

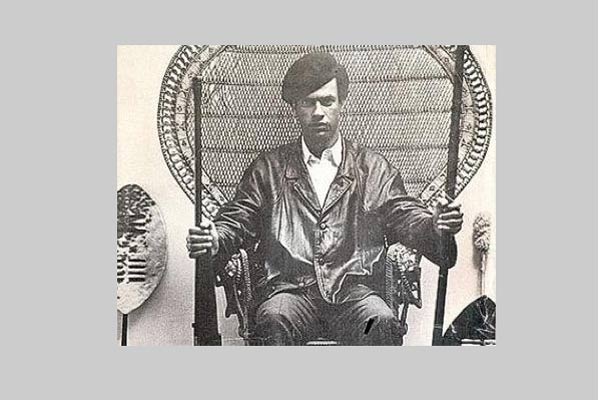

McNair began working for her master’s thesis at UCLA by examining radical iconography from the 1960s and ’70s and how those images have been appropriated and altered in media, advertising and social movements and by succeeding generations.

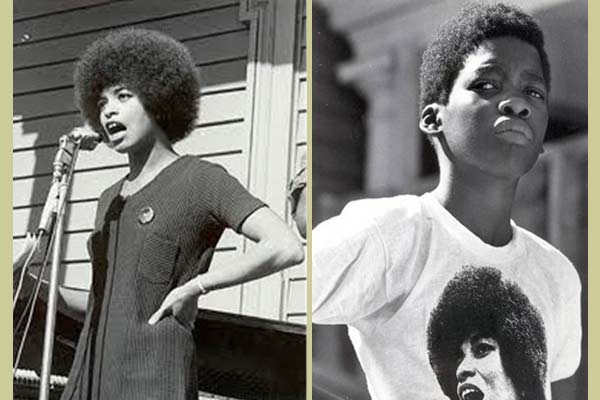

She recalls feeling intrigued by the frequent sight of undergrads clad in graphic t-shirts of Che Guevara, Angela Davis and other “notorious and notable people from the ’60s. I was puzzled by what meaning people drew from these images on their T-shirts” — whether purchased for $10 from a street vendor in south L.A. or for $40 at Urban Outfitters — and “what work was that doing in their own particular context.”

Was a T-shirt created by a grassroots organization to raise consciousness or funds, or was it offered by a strictly commercial venture? When worn in public, does it serve to start a conversation? To preserve history, articulate a struggle or memorialize a martyr? All of these questions interest McNair, whose own collection of socially relevant Ts includes a favorite featuring a James Baldwin quote: “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.”

To McNair, “wearing history” is a type of performance, and those who don symbols of the African American protest tradition “extend and enliven that tradition by and beyond aesthetic means.”

A photo of activist Assata Shakur appears on a Liberation Ink T-shirt, with a quote from Shakur on the back: “It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win. We must love each other and support each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains.” McNair says she wears the shirt when she’s “ready for the conversation” it evokes. “I like ‘Who’s that?’ and ‘Why?'” (Photo on left by Seth Newton Patel, circle design by Emunah Yuka Edinburgh)

She notes that T-shirt culture “really picks up around 1975 and into the early ’80s,” as advances in printing technology made it possible to produce T-shirts in quantity outside of clothing factories, in the home or small shops. The advent of online, for-profit merchandise hubs like Redbubble and CafePress — which will print your design on a mug, mouse pad or T-shirt — further transformed the industry.

McNair was raised in a small town in eastern North Carolina, within sight of one of the area’s large clothing factories, where her mother worked for four decades sewing T-shirts and other apparel. “I grew up in the shadow of the Kinston shirt factory,” she says.

Only well into her research, though, did she realize how thoroughly “my mother’s experiences resonated in my project,” as she puts it. Cotton, the North Carolina apparel industry and a “tradition of Black Southern radical political activism” that included her parents — “I grew up around this all my life.

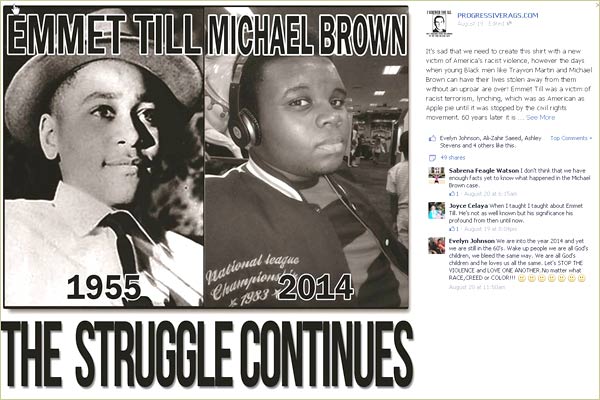

But the tradition of the black-protest T-shirt has taken a turn, McNair says: In the past, many such Ts bore the image of an iconic political activist. Now, with sad regularity, they commemorate an unarmed African American citizen — a Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride or Michael Brown — killed by a policeman, vigilante or fearful citizen during activities “of a private nature,” be it “going to the store to buy a pop and some Skittles” or “going up on someone’s porch to ask for help” when your car breaks down.

“A moment becomes a movement; that is very much a now, contemporary concern.”