Love and loss drive campus ‘Day of the Dead’ art show

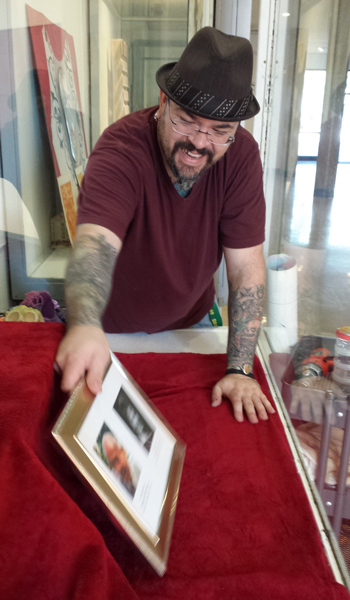

Jason Thomason claims no Mexican heritage. But since several of his friends died young from hard living, he has found solace in the Day of the Dead, which comes on the heels of Halloween. The art practice student has curated a Dia de los Muertos exhibit for his senior class project in Kroeber Hall.

October 31, 2014

Jason Thomason claims no Mexican ancestry. But since several of his friends died young from hard living, he has found solace in the Day of the Dead, which comes on the heels of Halloween. So much so, in fact, that the UC Berkeley art practice student has curated a “Dia de los Muertos” exhibit for his senior class project.

A sculptor and installation artist, Thomason, 38, put on a similar exhibit when he was a student at Skyline College in San Bruno. At Berkeley, where sensitivities about cultural appropriation can run high, he had his doubts about taking on the exhibit. But when he got too worried, his mentor, Oakland composer and performance artist Guillermo Galindo, set him straight on the universal matter of death and dying.

“Death belongs to everyone,” says Thomason, invoking the words of Galindo. “Sure, I’m an outsider in the culture, but I’m approaching it with respect.”

Since last Tuesday, his Dia de los Muertos exhibit on the first floor of the campus’s Kroeber Hall has been growing little by little, and is scheduled to come down Nov. 5. More than 100 people attended a reception for the show on Sunday.

(Story continues below slideshow)

Rooted in indigenous Mexican culture

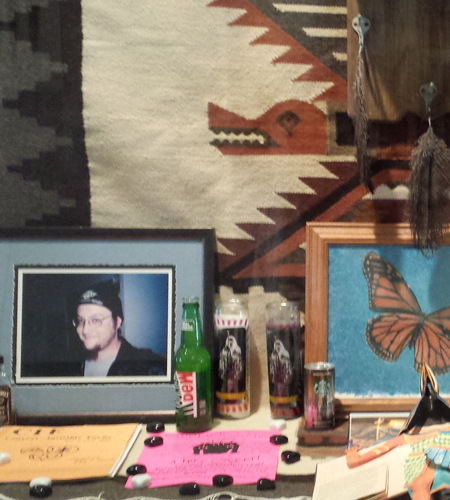

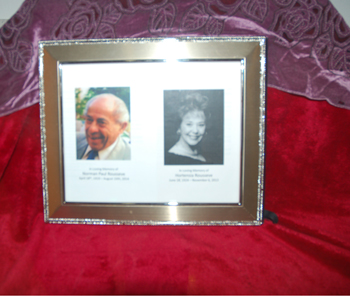

The show includes intricate altars, paintings, drawings and other artworks by Victoria Ayala, Kay Meyer, Aaron Nassberg, Teresa Smith, Isabela Novaka and Todd McKinney, among other art students. Also part of the exhibit is a community altar that Thomason hopes will be an annual tradition. Students, faculty and staff contributed offerings to their deceased loved ones for the altar.

“I want to create this space for grieving, healing and celebrating and have it continue for the students in art practice,” he says.

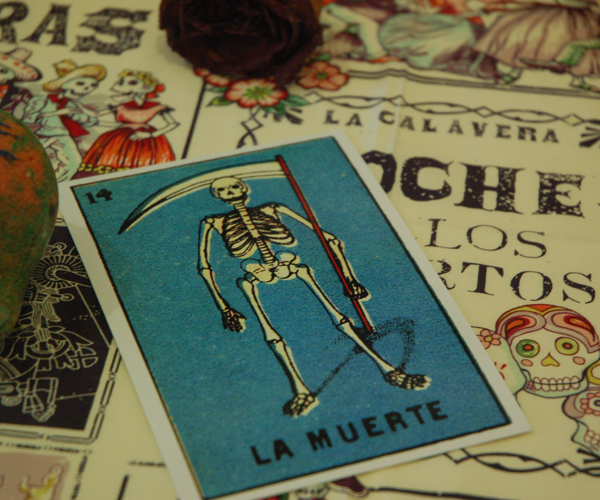

Rooted in indigenous Mexican culture and imbued with Catholic influences, Dia de los Muertos festivities can start as early as midnight on Halloween. On All Saints’ Day (Nov. 1), the gates of heaven are said to open to let in the souls of deceased children. Then, on All Souls’ Day (Nov. 2), they open again to let in the adults and, some say, pets. It is during this time that the division between the living and the dead is believed to be at its most vulnerable, making their reunification more possible.

This theme is popularized in Hollywood director Guillermo del Toro’s new animated movie The Book of Life, in which the glamorous La Muerte (Death), who rules the land of the remembered, loses a bet to the trickster Xibalba, who oversees the land of the forgotten. The bottom line? Life and death are a package deal.

“It is a powerful ritual because it reminds us that death is part of life,” says Carlos Munoz Jr., a professor emeritus of ethnic studies at Berkeley and founding chair of the country’s first Chicano studies department, at California State University, Los Angeles. “I don’t think it has political or social value. It is more cultural and to some extent therapeutic because it helps those who have lost family members and close friends to mourn them in a more celebratory way, as opposed to sadness only.”

Love and loss drive the show

A native of California who has lived in Texas, Oklahoma and Bogota, Colombia, Thomason has seen his share of debt, divorce and early demise: “Unfortunately, a lot of my friends played hard and died young,” he says. “I’m lucky to be alive.”

At the community altar, Thomason placed a Starbucks double shot in memory of his best friend, who died of a heart attack in 2007 (he was too distraught to attend his funeral), and a bottle of Mountain Dew for another close friend who died of an overdose in 2005.

Also planning to participate in the event was Luis Venegas, whose 27-year-old uncle Rodolfo was killed in a drive-by shooting in Mexico. To keep alive his uncle’s memory, Venegas has adorned a household altar with photographs, flowers, candles, food and other mementos, a ritual that is new to him and many of his relatives.

“Somewhere along the line, we got disconnected from our culture,” Venegas says. “But celebrating Dia de los Muertos in this way is beautiful. It’s precious, and valuable. There are so many stories to be shared.”