Wealth, power or lack thereof at heart of many mental disorders

Donald Trump’s ego may be the size of his financial empire, but that doesn’t mean he’s the picture of mental health. The same can be said about the self-esteem of people who are living from paycheck to paycheck, or unemployed. New research underscores this mind-wallet connection, showing a strong link between self-worth and mental illness.

December 9, 2014

Donald Trump’s ego may be the size of his financial empire, but that doesn’t mean he’s the picture of mental health. The same can be said about the self-esteem of people who are living from paycheck to paycheck, or unemployed. New research from UC Berkeley underscores this mind-wallet connection.

Study finds self-worth plays a key role in the diagnoses of psychopathologies.(iStockphoto)

Berkeley researchers have linked inflated or deflated feelings of self-worth to such afflictions as bipolar disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, anxiety and depression, providing yet more evidence that the widening gulf between rich and poor can be bad for your health.

“We found that it is important to consider the motivation to pursue power, beliefs about how much power one has attained, pro-social and aggressive strategies for attaining power and emotions related to attaining power,” said Sheri Johnson, a Berkeley psychologist and senior author of the study published Dec. 10 in the journal Psychology and Psychotherapy:Theory, Research and Practice.

Ruthless ambition among key self-esteem measures

In a study of more than 600 young men and women conducted at Berkeley, researchers concluded that one’s perceived social status — or lack thereof — is at the heart of a wide range of mental illnesses. The findings make a strong case for assessing such traits as “ruthless ambition,” “discomfort with leadership” and “hubristic pride” to understand psychopathologies.

“People prone to depression or anxiety reported feeling little sense of pride in their accomplishments and little sense of power,” Johnson said. “In contrast, people at risk for mania tended to report high levels of pride and an emphasis on the pursuit of power despite interpersonal costs.”

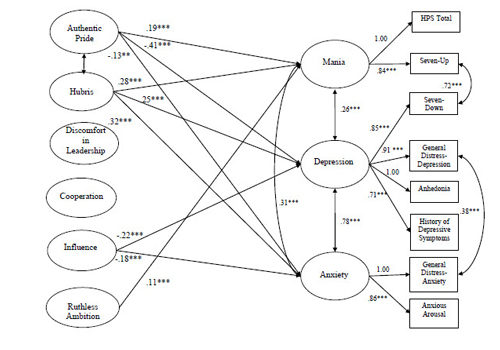

The study used several measures to correlate power and mental disorders (Courtesy of Sheri Johnson)

Specifically, Johnson and fellow researchers Eliot Tang-Smith of the University of Miami and Stephen Chen of Wellesley College looked at how study participants fit into the “dominance behavioral system,” a construct in which humans and other mammals assess their place in the social hierarchy and respond accordingly to promote cooperation and avoid conflict and aggression. The concept is rooted in the evolutionary principle that dominant mammals gain easier access to resources for the sake of reproductive success and the survival of the species.

Income inequality linked to poor mental health

Studies have long established that feelings of powerlessness and helplessness weaken the immune system, making one more vulnerable to physical and mental ailments. Conversely, an inflated sense of power is among the behaviors associated with bipolar disorder and narcissistic personality disorder, which can be both personally and socially corrosive.

Recent studies have found that people living in developed countries with the highest levels of income inequality were three times more likely to develop depression or anxiety disorders than their more egalitarian counterparts. Similar results were found in a state-by-state comparison of income and mental illness in the United States.

For this latest study, 612 young men and women rated their social status, propensity toward manic, depressive or anxious symptoms, drive to achieve power, comfort with leadership and degree of pride, among other measures.

In one study, they were gauged for two distinct kinds of pride: “authentic pride,” which is based on specific achievements and is related to positive social behaviors and healthy self-esteem; and “hubristic pride,” which is defined as being overconfident and is correlated with aggression, hostility and poor interpersonal skills.

And in a test for tendencies toward hypomania, a manic mood disorder, participants ranked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with such statements as “I often have moods where I feel so energetic and optimistic that I feel I could outperform almost anyone at anything,” or “I would rather be an ordinary success in life than a spectacular failure.”

Overall, the results showed a strong correlation between the highs and lows of perceived power and mood disorders.

“This is the first study to assess the dominance behavioral system across psychopathologies,” Johnson said. “The findings present more evidence that it is important to consider dominance in understanding vulnerability to psychological symptoms.”