San Francisco’s homeless youth at 10 times higher risk of death

Street-based study shows suicide, substance abuse main cause of mortality among homeless youth

April 14, 2016

A UC Berkeley study of homeless youth living on the streets of San Francisco found that they have a 10 times higher mortality rate than their peers, mostly due to suicide and substance abuse.

Homeless youth living on the streets of San Francisco have a 10 times higher risk of dying than the average youth of their age, race and gender, according to a new UC Berkeley study. (iStock photo)

“This population is highly stigmatized. That stigma leads to neglect and, in turn, to increased mortality. All the deaths in this cohort were preventable,” said the study’s main author, Colette Auerswald, a pediatrician and adolescent medicine specialist who is an associate professor of public health at UC Berkeley. “Stigma kills.”

The study will appear online April 14 in the open-access journal PeerJ. Auerswald, co-founder of Innovations for Youth (I4Y), the UC Berkeley School of Public Health’s center for adolescent population health, co-authored the study with Jessica Lin of UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health and Andrea Parriott of UCSF’s Phillip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies.

“These sobering data provide evidence of what homeless youth face when their only option is life on the streets,” added Sherilyn Adams, executive director of Larkin Street Youth Services in San Francisco. “We must not ignore or underestimate the gravity of homelessness or its tragic impact on young lives cut short. No young person deserves to die a preventable death because they didn’t get the help they needed.”

The most recent HUD-mandated point-in-time count in San Francisco, mandated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, led to an estimate that 1,378 homeless young people are on the streets of San Francisco on any given night, though most of them cycle in and out of their homes because of abuse, family problems or drug use, Auerswald said. In an editorial she wrote last week for the journal JAMA Pediatrics, she praised a new study that reinforced the fact that homeless youth are not homeless by choice.

“That study once again blew out of the water the myth that youth either choose to be on the street or are on the street because they are delinquents,” she said. “For the vast majority of youth in developed countries, homelessness is due to abuse or neglect or family conflict, often related to poverty.”

SF’s homeless youth

Auerswald’s study was conducted between 2004 and the end of 2010 as part of a larger longitudinal study of the effect of social environments on the health of homeless youth in San Francisco. The study involved 218 youths 15 to 24 years of age, two-thirds of them male and one-third female. Young people were considered to be homeless if they reported unstable housing for at least two days during the previous six months — that is, they lived outside their home with non-family members, such as in a car, a shelter, a squat, outdoors, with a stranger or someone they did not know well, on public transportation or in an SRO hotel.

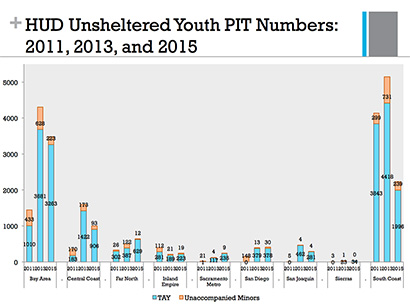

Point-in-time counts of homeless youth under 25 in California in 2011, 2013 and 2015, showing an increase in almost all regions of the state. The data on transitional age youth (TAY), mandated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, is almost certainly an undercount, according to Colette Auerswald.

During that six-year period, 11 died – eight men and three women, or 5 percent of the study group – 10.6 times higher than expected for a similar group matched for age, race and gender. Six of the deaths took place outside California.

Three of the deaths were suicides, one was a homicide and the others were related to drug or alcohol use, either from an accidental overdose or disease linked to substance abuse or sexual behavior. One youth died from complications from HIV, a death that was also preventable, Auerswald said.

Auerswald acknowledged that the study was relatively small, but its findings are in line with other data in Europe and the U.S. that reported deaths of youths as subsets of studies of the general homeless population. A recent census-based study of life expectancies in Canada found that a 25-year-old male living in shelters, rooming houses or hotels had a 32 percent chance of surviving to the age of 75, as compared to 51 percent of housed males from the lowest-fifth income bracket.

“This is the first North American study of mortality, and the only one I know of globally, focused solely on a street-based cohort of youth,” Auerswald said.

The study was unique in that Auerswald and her colleagues actually went out on the street to survey homeless youth, instead of seeking them out at programs or drop-in centers for homeless youth. Such program-based recruitment produces a biased sample favoring lower-risk youth who access services, she said. Homeless youth are challenging and expensive to count, in part, because some youth of color – African Americans, Hispanics and Latinos in particular – do all they can to conceal the fact that they are homeless. Homeless white youth in San Francisco – who comprised half the study subjects – are more likely to openly sit on sidewalks or engage in activities such as panhandling that readily identify them as homeless.

Funded by the California Homeless Youth Project through a grant from the California Wellness Foundation, Auerswald and Lin developed and implemented We Count, California!, a statewide technical assistance program to increase capacity for conducting more inclusive counts of homeless youth.

Drug use and death

One of the study’s takeaways is that injection drug use is a potential predictor of street death for homeless youth. Two-thirds of those who died had injected drugs at some point, as opposed to one-third of survivors.

“It is critical that we have on-demand access to substance abuse treatment for all youth, including minors, in San Francisco, where drugs are a huge problem regardless of homelessness,” Auerswald said. “Drugs are a major cause of morbidity and mortality and of the failure of young people to remove themselves from the street.”

In this study, young women had a higher risk of death compared to their female peers, exceeding the increased risk of death among homeless young men compared to their peers. Young women had a mortality rate 16.1 times greater than their race- and age-matched female peers. The homeless young men were 9.4 times more likely to die than their race- and age-matched male peers.

“Being homeless is dangerous for everybody, but the social environment of the street is particularly treacherous for young women,” she said.

In the end, she said, it is not normal, healthy or safe for young people to live on the street.

“The bottom line is to have a society that gives youth safe options for not living on the street, that does not tolerate youth homelessness as an acceptable option for our youth,” she said. “Yes, provide shelter and substance-abuse counseling, but also provide access to housing and education, instead of passing no-sit, no-lie laws that criminalize youth, make it harder for them to access housing or funding for schooling and keep them on the street. Not having a way out leads to survival behaviors that place them at high risk of preventable death.”

“Research like Dr. Auerswald’s,” Adams said, “shines a spotlight on the severity of this issue, and it demands that communities find real, immediate and sustainable solutions — from crisis intervention to long-term housing — so vulnerable youth have better options than living or dying on the streets.”

The study was funded by the Eunice Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Development of the National Institutes of Health.

RELATED INFORMATION

- Six-year mortality in a street-recruited cohort of homeless youth in San Francisco, California (PeerJ)

- Stigmatizing Beliefs Regarding Street-Connected Children and Youth: Criminalized Not Criminal (JAMA Pediatrics)

- I4Y (Innovations for Youth)

- We Count, California! (PDF), a report on homeless youth by the California Homeless Youth Project