War wounds lead graduating veteran to new mission

Almost fatally injured in Iraq, Brian Vargas is graduating next week and aims to save veterans' lives as a social worker

May 4, 2016

Bleeding profusely in a medic’s arms, 19-year-old U.S. Marine Lance Cpl. Brian Vargas felt his life slipping away. It was Jan. 17, 2007, in Iraq’s Triangle of Death, and enemy gunfire during a rooftop battle had exploded a 500-round ammunition drum near Vargas, blasting him backward onto his head and peppering his body with shrapnel. A bullet hole was in his left hand, a deep gash in his right cheek.

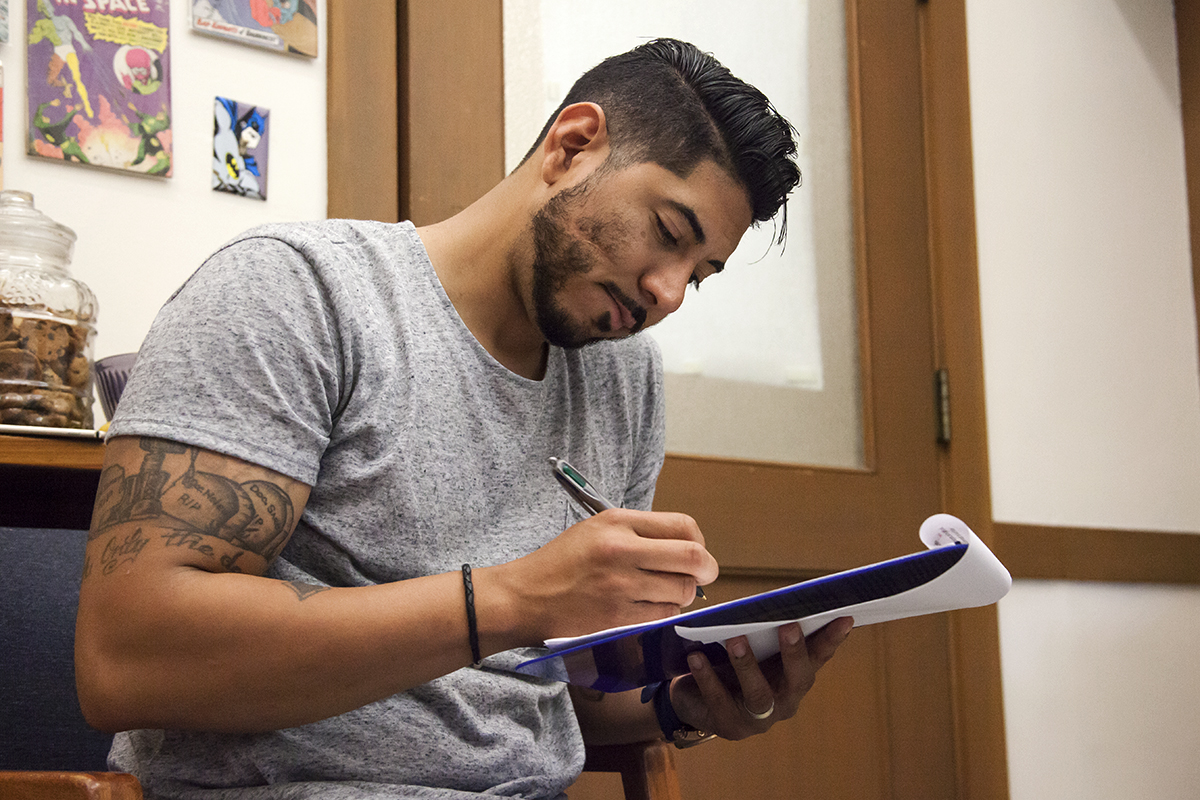

Vargas says military skills like teamwork, attention to detail, discipline and time management help him in academia. (UC Berkeley photos by Brittany Murphy)

“The day had felt different, waking up. I knew it was going to be rough,” says Vargas, who with several Marines was in the city of Hīt to support an Army tank unit. “Hīt had gotten out of control, and we were trying to take it back. The Bradley tanks were being split in half by IEDs (improvised explosive devices). It was a very dangerous situation. Everyone was against us.”

As a full-scale battle erupted, Vargas heard the medic plead, “Don’t die, Vargas! Don’t die!” But “I left my body,” he says, “I was floating and could see everything. There was no pain. Euphoria can barely describe it. I felt God’s presence… But I remember feeling, ‘Not now.’” And he returned to the chaos.

Today, nearly a decade later — and despite 10 surgeries, 188 other medical procedures, nearly three years in a Wounded Warrior battalion and persistent insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and chronic back pain — Vargas not only is alive, but will graduate this month from UC Berkeley. He has a 3.5 GPA, plans for graduate school, a wife, a home, three dogs and a new life’s mission.

“I can’t be on the battlefield running and protecting people anymore, but the strong pull I feel now is social work, to work with veterans face-to-face,” the 29-year-old Antioch resident says. “I know I can help in that role. I can be of value and save lives in the process.”

In addition to outreach work at the Cal Veteran Services Center, Vargas already has helped Diablo Valley College plan a new veterans resource center and, with a U.S. Veterans Administration psychologist, is designing a novel method of deterring veterans from impulsive firearms suicide. On June 1, he’ll start working as a constituent representative for U.S. Rep. Eric Swalwell, a Democrat who serves parts of Alameda and Contra Costa counties and says he’s “in awe of Brian’s accomplishments.”

“Nothing Brian does in the future is going to surprise me,” says Sherman Boyson, undergraduate adviser at Berkeley’s School of Social Welfare, which chose Vargas to speak at its May 14 graduation ceremony. “How do you keep going after you’ve been in combat? He just perseveres. He’d be a great candidate to run for office, to fight for social justice and military benefits. He’s someone you’re going to read about.”

Family for life

Vargas, whose father also was a Marine, was the oldest of eight children in a Bay Area household that he says “wasn’t always the best, or always safe.” His parents began raising their youngsters in San Francisco, but divorced before Vargas reached middle school. During his K-12 years, Vargas lived at 17 different addresses.

At Antioch High School, where he transferred midway through freshman year, he met his future wife, Monica. “Brian was always that confident, funny guy that everyone loves,” says Monica Vargas, 29. “He caused a little trouble in school, but during senior year, you never saw a teenager turn around so fast — the way he talked, the way he dressed. He wanted to join the Marine Corps.”

“Even through hard times,” says Monica Vargas, “we were meant to be together.”

Brian Vargas also wanted to impress his girlfriend — and her parents. “I wanted to pull my weight for the country and fight,” he says, “but I also wanted to be a better person for Monica, to learn discipline and life skills. It wasn’t too hard to see there was something there to hold us together forever.”

After graduation in 2005, Vargas entered training school for the infantry, which suffers the greatest number of war casualties as “the tip of the spear when forces are deployed,” says Vargas. His Marine Corps unit, stationed in Twentynine Palms, California, was deployed to Iraq in September 2006.

“I loved every minute of my life in the Marines,” says Vargas, and he grieved for it during his recovery in Southern California at the Wounded Warrior Battalion-West, in Camp Pendleton. “My unit was in Iraq and Afghanistan, and I felt like an outsider,” he says. “We were a family. We shed blood, we shed tears together.”

Monica and Brian Vargas also became distant. “In Iraq, Brian had rarely called,” Monica Vargas says. “After he was put in the Wounded Warrior battalion in February 2007, we stopped talking, we disconnected.” But she chose to wait for him.

“I was mad about everything,” explains Brian Vargas. “All of us wounded warriors were pretty much broken. I was undergoing surgeries. I had deep scars in my face, my tongue, my ear. Shrapnel in my face, my eye. Two herniated disks. I was being treated for traumatic brain injury. I had to start over, learning to write and put words together.”

More trauma followed. While in a three-month PTSD program at a VA facility in Menlo Park, Vargas’ close friend, Iraq veteran Sean Webster, committed suicide. Upon Vargas’ return to Wounded Warrior Battalion-West, he learned that a few more Marines had taken their lives, and others had tried.

Community within a community

In August 2009, Vargas, then 22, left Camp Pendleton and arrived in the Bay Area homeless. His parents had moved, separately, to Florida, his siblings had scattered. He sometimes stayed with his grandparents in Concord, uncles in Santa Clara, and in Antioch with his long-lost girlfriend’s family — the couple, reunited, had become engaged and would marry in May 2010.

“But I spent a lot of time sleeping in my car. I didn’t want to overstay my welcome,” he says. Friends and relatives he couch-surfed with didn’t always welcome Bailey, a black Labrador and Vargas’ first service dog.

Nala, Vargas’ service dog, pays a visit with him to the School of Social Welfare.

When Vargas enrolled at Diablo Valley College in January 2010, his black Pontiac G6 came in handy again. “He’d stay in his car, go to class, and return to his car,” says David Vela, an English professor at DVC. “I saw his intensity of focus and his tattoos right away and knew he was a vet. It took a lot of courage for him just to be on campus.”

“I was very withdrawn from people. I felt the need to be guarded,” Vargas explains. “Because of my back pain, I had to stand up during class, and I still do. People looked at me, judged me. And it was a lot for my brain to stretch and be focused for long periods of time.”

Still, Vargas was earning As, including as top student in Vela’s critical thinking course. “David told me I had a lot to say, to share my military experience in class and write about it,” says Vargas. “He helped me realize I could use what I learned in the Marines — like attention to detail, time management, leadership — to be productive at school. It was eye-opening.”

He also applied those skills to a new goal: a resource center for the 400-plus veterans at DVC. The 47-page research report that Vargas co-produced with DVC student-veteran Ryan Kelley proved the need for a center, which will open soon, and is helping Los Medanos and Contra Costa community colleges follow suit. Los Medanos College held a ribbon-cutting ceremony for its center last month.

“Transitioning from a war zone to a college campus is extremely difficult. If vets have their own space at school that’s comfortable and safe, they feel more at home,” says Vargas. “People don’t realize we have flashbacks on campus sometimes, react to construction noises, to someone running quickly behind us.

“For me, it’s huge crowds. Sproul Plaza, with protests and people handing you flyers and things, can remind me of marketplaces I patrolled for anyone trying to attack civilians. I used to search people’s hands, eyes and feet. Feeling that hyper-vigilant can get me so worked up that I get to class uncomfortable and mentally tired.”

A place to belong

Vargas, who retired from the Marine Corps in 2013, next set his sights on transferring to a four-year school. “Berkeley was the furthest thing from my mind,” he admits. “I felt like I wouldn’t belong.” But Vela insisted he apply and asked veteran Andrew Medina, a former Marine and then-president of the Cal Veterans Group, to give him a tour. By the end of the day, Vargas had changed his mind.

He stopped by the School of Social Welfare, where he met Boyson. “I knew social work was my route,” says Vargas. “I’m a student who’s had a social worker or two in my life, and I’m the product of good ones and bad ones. I want to be one of the good ones who makes a difference in people’s lives.”

An aspiring social worker who wants to work with veterans, Vargas says he hopes to follow Berkeley’s motto, “Fiat Lux,” and “be that light in the darkness” for others.

A growing number of Berkeley student-veterans are social welfare majors aiming to work in veteran services, says Boyson. “They go on to get their MSW (master’s degree in social work). There have been about a dozen in the last five years,” he adds. “Many realize veterans need a lot more help; they’re being redeployed faster than any mental health guidelines would suggest.”

At the Cal Veteran Services Center, Vargas impressed Luis Hernandez, veterans academic achievement counselor.

“Berkeley has a reputation for giving back to the community,” says Hernandez, “and veterans like Brian are the epitome of the kind of students it wants — they’ve proven themselves in service to the country and believe in service to others. And they continue, even as alumni, to give back.”

“Brian wants to honor the people he’s served with, and their memories,” adds Hernandez. “It’s what fires him up every day to do something in the world.”

Before long, Vargas was on the Campanile’s observation deck, visualizing himself as one of the thousands of students walking to class below.

“I thought, ‘I can do this. There are vets here, vets who have gone through combat,’ and it felt like the right move. And I knew that the top instructors in my field would give me the ability to make a difference wherever I go,” says Vargas. He joined the Berkeley student body, which includes some 300 student-veterans, in fall 2014. And he did so with a Regents’ and Chancellor’s Scholarship, the most prestigious scholarship awarded to incoming Berkeley undergraduates.

Something to live for

Most days, Vargas can push through his persistent physical pain. His wife’s love and his faith in God, he says, keep him “from living in a dark room, scared to even try.” It’s the suicide of his buddy, Iraq veteran Sean Webster, that he can’t shake.

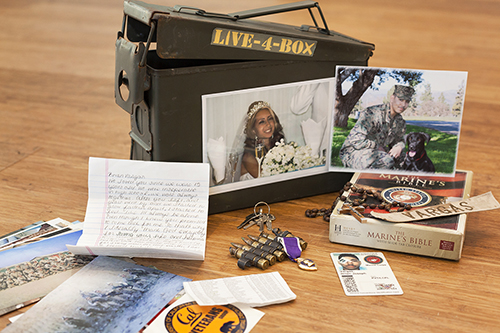

Vargas is helping a VA psychologist create the LIVE-4-BOX to prevent suicide among veterans. He put together his own as a prototype.

So he says he’s turning that tragedy into “the backbone” of the LIVE-4-BOX, a concept VA psychologist Dr. Shauna Springer asked him to help her develop as a way to prevent veterans from ending their lives. The pair now is seeking funding and support to take the project to the next level.

The idea is for a veteran to fill a special container with items “that money can’t buy, strong reminders of the person’s values and the people and things he or she lives for,” says Springer, a frontline mental health provider who treated Vargas for PTSD and anxiety.

It also would hold the key to a veteran’s gun safe. That way, Springer says, if a veteran is “hit by a wave of despair or fright, or if the wrong circumstances come into his life, or he’s been drinking” and gets the impulse to grab his gun, the box’s other contents might change his mind.

Vargas assembled one for himself using a green Army ammunition can. A photo of his wife on their wedding day is on the outside. Objects inside include her wedding vows, photos of his Marine Corps unit, a mini version of his Purple Heart, a rosary and spent mortar rounds from the 2007 attack and his loved ones’ contact information.

In a survey Vargas conducted of student-veterans at three schools, including Berkeley, says Springer, 75 percent of respondents felt the LIVE-4-BOX concept could “substantially reduce” impulsive firearms suicide. It’s meant to be used in conjunction with therapy, she adds, in a “conversation about higher values and what to live for.”

Veterans listed spiritual symbols, Bible verses, a list of travel destinations, precious photos of and letters from loved ones, military medals and commendations, and even running-shoe laces and “a reminder that Game of Thrones isn’t over yet” as items they’d cherish, she says.

“Brian wants to be a role model to others,” says Luis Hernandez, veterans academic achievement counselor at the Cal Veteran Services Center, “and he’s open to talking about his struggles.”

“Higher education also is worth living for,” says Vargas, adding, “I’ll forever be a Bear, just as much as I’ll forever be a Marine.”

“The Berkeley student-vets surveyed said it means so much to get a degree from Cal, to go into the career of their choice, and that they really feel accepted here on campus,” he says. “This education alone helps them choose to stay alive.”