Residential college redux: Bowles is back

Historic building welcomes a new generation after an 11-year restoration campaign

August 19, 2016

Berkeley’s Bowles Hall reopens this weekend as a residential college after an 11-year effort by alumni who raised $45 million to restore the aging, castle-like building and return it to its roots as a live-learn community for undergraduates.

Bowles Hall, which opened in 1929, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1989. (UC Berkeley photos by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Believed to be the nation’s first residential college, Bowles Hall opened in 1929 to male students who for four years would live, eat, study and be mentored there. But by the 1970s, Bowles was a conventional dorm for men. Meal service was cut in 2001, and in 2005 the hall housed only male freshmen. Over the decades, upkeep of Bowles, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, grew too costly for the campus.

Graduate student residents Rachel Roberson (left) and Sydney Aardal get familiar with Bowles’ Hart Library.

“Our life-changing Bowles Hall experience barely existed — the guaranteed four-year residency, sense of community, on-site dining, regular contact with graduate students, alumni and faculty,” says Bob Sayles, a 1952 Berkeley and Bowles Hall alumnus. The ambitious restoration campaign he led culminates Saturday, Aug. 27, in a daylong celebration.

This weekend, Bowles Hall Residential College will greet 183 new undergraduates — half of them women. Until they graduate, they’ll share the iconic hall on Stadium Rim Way with three Berkeley academics, an archaeologist who is a Bowles Hall alumnus and five graduate students.

Bowles Hall’s front porch has sweeping views of the campus and San Francisco Bay.

“This reopening, and the return of Bowles to its pioneering roots, represents a major step toward an entirely new undergraduate experience on the Berkeley campus,” says Chancellor Nicholas Dirks. “Nothing, in my mind, is better suited to providing and sustaining those invaluable educational and communitarian experiences than a residential college.

“For a while, only 183 students will have the privilege of calling this place home,” he adds. “But I see this as a pilot project, a vital step toward the day when we can and will offer housing in residential colleges to all our undergraduates.”

One new resident of Bowles, Henderson Wong, says most Berkeley students “move into private apartments after one year in a traditional dorm. But being able to stay in the hall for multiple years was an important factor for me and will allow me to be part of a community that’s much more stable.”

Wong led an effort with 37 other students to help shape

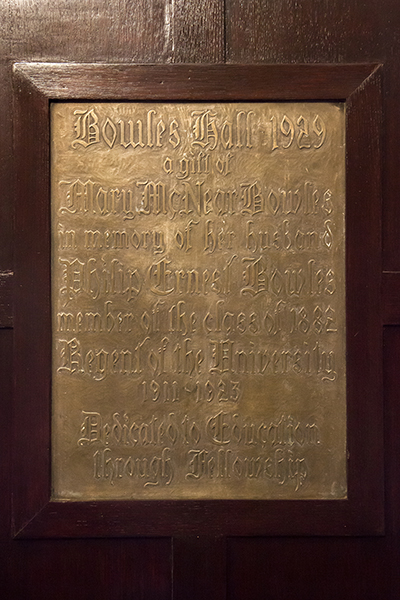

The motto “Dedicated to Education through Fellowship” is on a plaque that hangs in the hall’s entrance.

Bowles’ self-governing structure and social environment, which will include traditions old and new. A weekly sit-down dinner, a Yule Ball dance and a game called “the Thing” will stay, with hackathons and volunteer work added in.

“So much development happens for undergraduates outside the classroom, and an experience like students will have at Bowles can be transformative,” says Ph.D. candidate Rachel Roberson, who has a master’s degree in higher education administration and is one of Bowles’ new graduate student residents. “I’ve worked in and have respect for the traditional residence hall model, but I’m excited to help launch this innovative new community at Berkeley. Bowles will be a one-stop shop for our students.”

Labor of love

While doing research in the United Kingdom, Roberson says she was impressed by Oxford University’s centuries-old residential college system. Bowles was modeled after residential colleges planned for Harvard and Yale, which were influenced by those at Oxford and Cambridge. In these decentralized live-learn communities, faculty, graduate students and alumni are major influences on student life.

A July 2, 1926, photo shows Bowles Hall under construction. (Photo courtesy of Bowles Hall Foundation)

In 1930, UC President Robert Gordon Sproul advocated for the subdivision of big universities to preserve small campus virtues. Bowles Hall, he said at the time, “helps to do that, for it is a center where students live and work together, where contacts may be made with professors and officers of the university, where many of unlike minds may break bread together and learn from each other the joys of fellowship.”

Nearly 90 years later, professor emeritus Dan Melia, who is Bowles’ new principal, or “principal resident,” echoes Sproul’s views. “Berkeley needs smaller, cohesive housing units,” he says, “to give students a sense of belonging to something less abstract than a 30,000-plus student organization.”

“They eventually discover fraternities, sororities, singing groups, sports clubs and the like,” adds Melia, who lived and later worked in Harvard’s residential college system, “but living arrangements have become increasingly difficult as housing costs in and near Berkeley have risen inexorably. Students have dispersed and been crowded into less and less comfortable spaces.”

New furnishings in the lounge help retain the room’s historic charm. Portraits of Phillip and Mary Bowles underwent a conservation process before being returned to the wood-paneled room.

Back in 2005, Sayles and a handful of other “Bowlesmen” saw the same need and made a pact to reestablish the residential college. They set up the Bowles Hall Alumni Association and “grew their commitment into something marvelous,” says Bob Jacobsen, dean of undergraduate studies in the College of Letters and Science. “They sweated every detail to get the restoration right. It’s a testament to how the hall used to be, and how it soon will be again.”

“It was a labor of love,” adds the hall’s new dean, Melissa Bayne, a campus lecturer and director of the Department of Psychology’s Post-Baccalaureate Certificate Program.

Bowles alumnus Bob Sayles, a retired technology investment consultant, led the 11-year, $45 million restoration campaign.

Some 1,000 Bowles Hall alumni and friends helped, either by contributing funds to the non-profit Bowles Hall Foundation or lending professional expertise in areas including law, design and construction, collegiate housing and public-private financing. In 2015, the foundation signed a long-term ground lease with the campus to coordinate and finance the work and to govern operations. This public-private partnership will relieve the campus of Bowles’ operating and maintenance costs for 45 years.

“Not only was this the right thing to do for a historic architectural icon, but it was the right thing to do for the campus,” says Bob Lalanne, vice chancellor for real estate, adding, “Bowles Hall will become one of Cal’s best recruitment tools.”

Makeover for an icon

On a recent tour of Bowles Hall, the massive concrete structure between Memorial Stadium and the Greek Theatre was nearly ready for occupancy following 14 months of non-stop restoration work.

In place of the vintage 1928 elevator with a grill door is an ADA-compliant 2016 model that silently whisks passengers to and from floors three through seven. (An eighth level contains an attic, with a staircase leading to the tower and its flagpole.)

The hall has 40 one-person and 73 two-person rooms.

Gone are the three-room, four-person suites, replaced by 40 one-person and 73 two-person rooms, all with Wi-Fi, heat and bathrooms. In the past, students walked down the hall one way for showers, the other way for toilets. The concrete hallway flooring has been carpeted. An apartment for Melia and his wife, Berkeley lecturer Dara Hellman, and another for Bayne, are on the fifth and sixth floors.

“Part of the value of having a tenured faculty member in residence is that students can see what a professor actually does outside class in terms of daily routine, classroom preparation and the like,” says Melia, who will be the hall’s foremost academic leader.

Sayles and Melissa Bayne, the hall’s new dean, walk through the updated dining hall, with its rebuilt iron light fixtures and flat screen TV.

After almost 20 years with no meal service, Bowles again has a dining commons. The room’s original iron light fixtures have been rebuilt, and two Olympic oars that once hung there – a gift from rowers David Brown and Lloyd Butler, who lived at Bowles and won gold at the 1948 London Olympics – will be back. (One oar, stolen, has been replaced). Students will be served meals prepared in a state-of-the-art kitchen contained in a new annex that also includes a game room.

A restored portrait of the late Phillip Bowles, a Berkeley alumnus and former UC regent, hangs over the fireplace in the lounge. His wife, Mary, had the hall built in his memory.

The lounge is fully redecorated, but Phillip and Mary Bowles’ portraits, which have undergone a conservation process, continue to hang prominently on the walls. In 1927, Mary Bowles gave the campus $400,000 to construct and furnish the hall in memory of her husband, a Berkeley alumnus and former UC regent devoted to the welfare of undergraduates.

Also restored is the grand wooden staircase that starts at the third floor entryway and the original wood-paneled walls. A committee of alumni and current students dedicated to Bowles’ Hart Library is working to update the selection of 2,000 books – only about 100 of which were published after 1960 – and to create an extensive collection of Blue and Gold yearbooks.

Louis Andreou Spanias, a 2014 graduate, describes what Bowles Hall meant to him in a message he left on the graffiti-covered attic walls.

The attic, where students have left graffiti for decades, will be kept as is, but access will be permitted only to those assigned to raise and lower the flag on the roof.

Also untouched will be the outdoor grave of Igor Fetch, a Bowles Hall pet in the 1970s, which is marked by a slab of dark granite engraved with his name.

“When I tell people I’m moving in, a lot of them seem to know Bowles Hall better than almost any place on campus except Memorial Stadium and the Campanile,” says graduate student resident Sydney Aardal, an aspiring science teacher with experience in outdoor education and as a math tutor and college success mentor. “It’s exciting that so many generations have had a vivid experience with this building.”

New generation, new day

Louis Grivetti, a UC Davis professor emeritus who lived in Bowles Hall from 1956 to1960, says it’s been important to him and others reestablishing the hall that their efforts aren’t “based on nostalgia, as opposed to what young people need and want today.”

Henderson Wong is part of a small core of students that helped plan Bowles Hall’s self-governing structure and social environment.

That realization initiated the Phoenix Project, in which a small group of undergraduates, including Wong, who would form the core of Bowles’ new student body, lived together during 2015-16 in The Berk, a former Berkeley sorority house, to experiment with self-governance, traditions and rules, setting the stage for a new day at Bowles.

Other newcomers with a diversity of voices and skills have joined older alumni in planning Bowles’ reincarnation.

Isaac Jackson graduated from Berkeley in 2012. He lived at Bowles when it was a residence hall and now sits on the Bowles Hall Foundation’s board of directors. (Photo courtesy of Isaac Jackson)

Isaac Jackson, 27, a 2012 Berkeley graduate who lived at Bowles first as a student and later as a resident adviser when it was an all-freshmen men’s residence hall, is one of them. Now a graduate law clerk in the San Diego County District Attorney’s Office, Jackson sits on the Bowles Hall Foundation’s board of directors and was on the five-member selection committee that chose the hall’s new student body.

“When I was at Bowles, I was only one of four black males there,” he says. “Bob (Sayles) actively sought to have a diverse board of directors and wanted the composition of the hall to reflect the campus community. The application process was blind, but we sought students who would bring different perspectives, different world and cultural views and life experiences. And, of course, it’s now co-ed.”

Jackson adds that the board made sure students could receive financial aid for room and board at Bowles, which is not part of the campus’s residence hall system. Eligible students will receive financial aid and scholarships aligned with the standard cost of room and board at a Berkeley residence hall, which is $14,992 for 2016-17. Bowles charges $19,356, a price more closely aligned with room and board costs for suites at Foothill and Clark Kerr housing.

Says Jackson, “We will be actively looking at raising scholarship funds for Bowles, to make sure it’s affordable for all.”

Bowles Hall alumnus John Baker, a retired civil engineer who oversaw the construction project, and Bowles’ dean, Melissa Bayne.

Bayne, the new dean, likewise was chosen to help launch Bowles for the unique skills she brings, including a background in community-based mental health.

Before coming to Berkeley in 2015, she directed the Sacramento Violence Intervention Program, which serves young victims of violent crimes. Her professional counseling work and research focuses on the mentorship of young adults. She says she is “excited to apply (her) expertise in coaching college-aged students toward supporting Bowles residents’ personal and professional success.”

The hall’s new live-in assistant dean and director of programs will be Alexei Vranich, a 1991 Berkeley graduate who lived at Bowles Hall and most recently was a visiting assistant professor of archaeology at UCLA.

Additional members of the Berkeley faculty, along with dozens of Bowles Hall alumni, will contribute time and expertise to the hall, whether giving internship and career guidance, leading a seminar or stopping by to share a meal.

“The building’s renovation is complete,” says Sayles. “But helping our students to graduate in four years, enter their chosen career or advanced academic program, gain necessary life skills and become informed, participative citizens is the most important component of all.”