Birthday Bear: Iconic Oski turns 75

Campus to celebrate its mischievous, lovable mascot and his milestone

September 26, 2016

With his trademark cardigan, white gloves, high-stepping gait and goofy grin, Oski, UC Berkeley’s mascot, was created in 1941 to embody a perpetual college sophomore – growing in wisdom, but not yet grown up.

This week, Oski turns 75, but remains more sophomoric than geriatric. Busier than ever with some 300 events a year and his own Twitter handle, Facebook page and Lair of the Golden Bear camp, the furry-headed, mischievous icon isn’t about to retire, or act his age, anytime soon.

Oski contemplates how to blow out the candle and eat his cupcake with a mouth that doesn’t open. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

“Oski has a wide-eyed, childlike view of Cal, as if he’s thinking, ‘I can’t believe I’m here,’ and that’s Oski every day,” says Mal Pacheco, a Cal Athletics volunteer adviser to the campus’s Oski Committee. “He personifies Cal spirit, and as long as Cal is Cal, Oski’s going to be that Cal spirit.”

Oski’s milestone birthday, Tuesday, Sept. 27, will be celebrated in a belated, but bear-sized, way. Events include a Homecoming 2016 pep rally on Sproul Plaza at noon on Friday, Sept. 30; a public lecture immediately after that, at 1:15 p.m., called “Oski Bear and the Struggles of Being a 75th-Year Sophomore;” an Oski hat giveaway on Saturday, Oct. 1, at Homecoming headquarters before the Cal vs. Utah game; a ticketed Bear Affair Tailgate BBQ; and a special tribute on the football field.

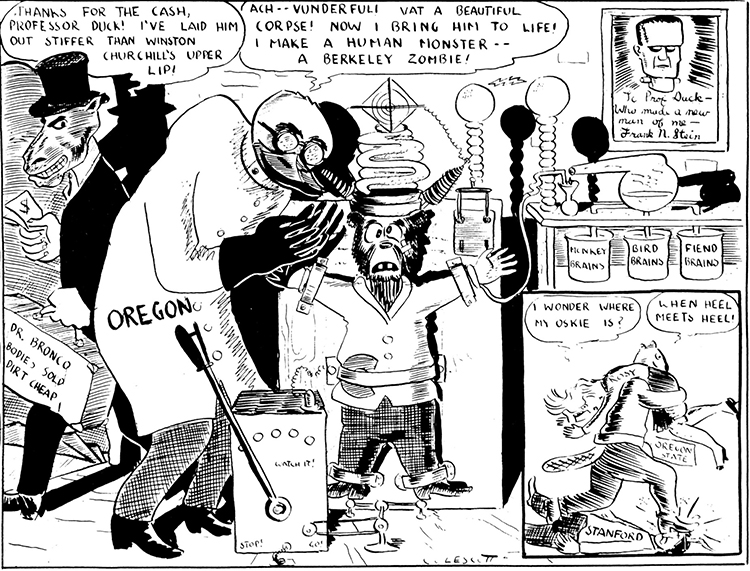

A pre-World War II character in a Daily Californian cartoon strip that quickly became three-dimensional, Oski through seven decades has achieved the status of a beloved campus icon despite makeovers, faux paw and his occasional placement on Internet lists of the most unintimidating, creepy or ridiculous college mascots.

“If Mister Rogers and Yogi Bear were able to conceive a baby,” noted the Bleacher Report, for example, in a 2012 list of “15 Unintimidating Mascots Least Likely to Steal Your Girlfriend,” “Oski is the offspring that would result.”

But when Oski is joked about, his loyal fans just grin and bear it.

“Yes, he’s a bit creepy-looking and not as up-to-date as other Pac-12 mascots,” says Katie Russell, a member of the Cal Dance Team, which Oski crashes – often to steal pom poms – at athletic events. “But he’s our mascot, and since we’re the oldest UC campus, I think it’s quite fitting that he’s an old bear. I’d hate to see him take on a more modern look.”

So would other Oski enthusiasts, who can’t imagine a Cal game without him and request his presence at retirement parties, campus East Coast fundraisers, community events and weddings. He’s even walked a bride down the aisle. Oski cheers kids in the hospital and at the annual Berkeley Eggster Hunt and recently was in New York for a Good Morning America college game day special.

And all this without saying a word — well, his mouth is stitched closed — or giving away, or caring to flaunt, who’s inside that unbear-ably thick, heavy, often sweaty costume, in need of frequent dry cleaning.

“He sweats a lot, a lot, a lot, and the suit can stink,” explains Diane Milano, a longtime director of Cal spirit groups who retired last June. A rare look into Oski’s secret lair, or dressing room, revealed numerous bottles of air freshener and disinfectant. Oski keeps cool using another of his classic moves – sipping water through a straw that enters a hole in his right eye.

Also keeping mum are students on the secret Oski Committee, a group described as “Oski’s inner circle,” who use code words like “our friend” when talking about him with each other in public. The online application students fill out – when no one’s looking, of course — informs hopefuls that group members are “honor-bound to keep Oski’s secrets.”

“There are very few mascots across the country that have a secret identity like Oski,” says Milano. “We take pride that our mascot’s a secret, a tradition, that’s been handed down from year to year,” says Milano, “from one Oski to another.”

Aura of secrecy

The secrecy surrounding Oski began with William C. “Rocky” Rockwell, a transfer student from Long Beach Junior College who arrived at Berkeley in 1940. While in Southern California, he’d worn his school’s “Ole Olson the Viking” mascot suit at athletic events and a parade.

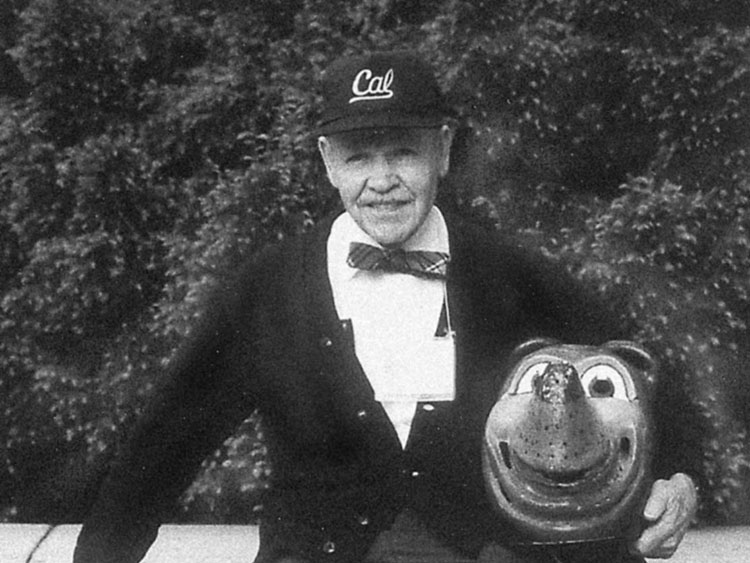

Student William “Rocky” Rockwell brought Oski to life in 1941. (Photo courtesy of Oski Committee)

At Berkeley, Rockwell thought it was time to replace the live bears being used as school mascots – the first was a cub donated to Berkeley in 1930 – with one that couldn’t grow big and unruly.

He created a bear suit by sewing together two pairs of old pants, painting some large football shoes gold, putting stomach padding inside a baggy sweater and adding a pair of gloves. He made a mold for a bear head – with two big front teeth – out of clay, shaping it around an old football helmet.

Then-Daily Cal art editor Warrington Colescott helped Rockwell brainstorm facial expressions for the bear and offered the name Oski, instead of Rockwell’s suggestion of Algy. “Oski Wow Wow” had long been part of spirit yells at Berkeley and other schools, and the word oski, or the acronym OSCI (other side caught it), was a football term.

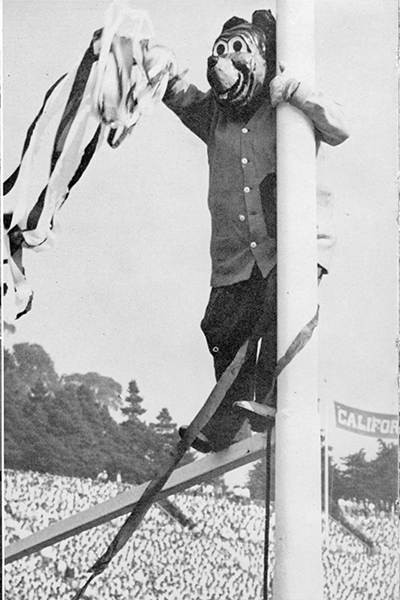

Oski balances on a goal post in the 1950s at Memorial Stadium. (Photo courtesy of Oski Committee)

Oski soon became a hit at athletic events, leading cheers at games, waving to children, flirting and even walking across the crossbar of goal posts. But Rockwell never let on that he wore the costume, which he hid under the bleachers.

Being Oski also allowed Rockwell, who Pacheco says was so painfully shy he rarely made eye contact with people, “to do things he normally couldn’t do. When he put on the costume, Rocky didn’t exist. Oski was his alter ego.”

“He also wanted none of the limelight for himself, and created an aura around Oski,” he adds, “a mystique that’s been kept alive, in part because of the Oski Committee.”

That committee formed in the early 1940s because Oski’s growing popularity caused worry that the mascot could be kidnapped. The Rally Committee decided he needed a separate entity, the Oski Committee, whose members transport and escort him safely and secretly to events.

For decades, until campus budgets tightened, says Pacheco, when Oski went to events, whether local or overseas, “he traveled separately, so no one knew who he was.”

Oski in the 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Oski Committee)

“After that, when we’d go to football games,” says Milano, Oski would board the bus in his civilian guise, “but if anyone in the marching band or spirit groups knew, they would never say a word.”

Even in 1999, when Milano began supervising the Oski Committee, which purportedly includes students who become Oski, “the members were tight-lipped about who was on it. I only worked with the chair; I didn’t know anyone else.”

As for Oski’s identity, “One alumnus told me he always suspected his roommate from the ‘60s was Oski, but he still doesn’t know,” says senior Andy Keeton, chair of the current Rally Committee. “And they’re best friends.”

A mischievous bear

Rockwell joined the Navy in July 1942 and formed a “Flying Golden Bear Squadron,” which included several other campus servicemen. He also designed the squad’s emblem — Oski charging over the clouds, carrying a lightning bolt like a marching baton.

Joining an ROTC activity, Oski rappels down the side of Wheeler Hall on Cal Day 2001. (UC Berkeley photo by Ben Ailes)

But upon returning to campus in 1946, “The rah-rah spirit wasn’t with me after the excitement of war… Flying airplanes in combat (was) a lot more interesting than playing around on a football field,” Rockwell said in a 1999 Regional Oral History Office interview. He began to give the role of Oski to others, and a student group that later became the Oski Committee soon took over.

For many decades, the committee was one of many Associated Students of the University of California (ASUC) organizations. The ASUC funded the committee, which was self-governing and interacted with campus officials only “when the administration had a request or concern,” says Pacheco.

Oski can’t bear to look when the game goes south. Or is he embarrassed by his own behavior? (Photo courtesy of Oski Committee)

Major concerns surfaced when Oski got into headline-making mischief, such as throwing a layer cake like a discus into a crowd at an Oregon State University basketball game in 1990 and hitting 15 people, including the mother of the school’s point guard, All-American candidate Gary Payton. Oski was suspended from the next two home games.

William Manning, then-director of Berkeley Recreational Sports, told The New York Times that Oski’s behavior had been deteriorating and also included inappropriate gestures, drinking alcohol on the job and “growling at people.”

“Young people look to Oski as something almost mythical,” Manning wrote in a memo to the Oski Committee at the time. “It demands extraordinary behavior, and we’re just not getting it.”

In 2012, Oski visited the Nanofabrication Lab at Sutardja Dai Hall. (UC Berkeley photo by Preston Davis)

Tussles with Stanford’s tree mascot also made news, including one at an ESPN-televised timeout during a February 1995 basketball game that left Oski headless and revealing the identity of the student in the costume. Other bear versus tree incidents continued into the 2000s.

Alumnus Nadesan Permal, now a Berkeley adjunct faculty member, was dispatched to be an adviser to the Oski Committee in 1990. “If they didn’t meet with me,” he recalls, “they weren’t allowed to operate.” Next on Oski duty was Milano, who also was an intermediary between the campus and the committee.

“I talked with the kids, set some ground rules,” says Milano. “Oski would have to be breathalyzed before games, and the UCPD supported me on these rules. I began managing his schedule and finances. Granted, they were a little upset with me, but things had to change, and they did.”

Save the bear

Oski frolics around the basketball court at Haas Pavilion. (Photo courtesy of Oski Committee)

One thing that’s never changed is Oski’s signature style, despite the passage in 1999 of an ASUC Senate bill calling for the makeover of the “poorly constructed and pathetic version of a bear.” Student leaders felt he needed to lose his pot belly, slouch and silly smile, wear hipper clothes and act more ferocious. Other students said he resembled a teddy bear, and that young kids mistook him for a dog.

“Just because he’s a mascot is no excuse for his decrepit condition,” then-ASUC senator Shireen Brueggeman told the San Francisco Chronicle, adding that relatively minor changes would make him more fit to be the mascot of a top college football team.

But Patrick Campbell, the ASUC president, vetoed that bill, saying, “Oski is an icon, and to change him would be a travesty.”

Oski sports his blue cardigan at a 2015 Cal women’s basketball vs. UC Riverside game. Behind him is a banner featuring a more ferocious Cal bear. (Photo courtesy of Oski Committee)

During that era, when superhero films like Spider-Man, released in 2002, were attracting a new generation of college students, says Pacheco, “Oski wasn’t what everyone thought a hero should look like.” A few years later, Nike introduced a new logo for a Cal Athletics bear that was vicious, with teeth bared. But the shoe company made sure older Cal images, including drawings of Oski, would remain on many of their items.

As Oski’s 75th birthday dawns, says Permaul, “What’s most important to me is that his tradition has been preserved, the one Rocky Rockwell created. But we need to make sure there will always be a conservator of that tradition, and that Berkeley’s cherished traditions are protected over time.”

“Students graduate every four to six years, including on the Rally Committee,” he adds, “and you don’t really know whether the base of knowledge about tradition is going to survive from year to year. For example, there was a time when many students knew the words to every song. Today, even members of the Cal Band do not know the words to every song. Part of Cal’s identity is keeping our student spirit and traditions intact.”

Oski often gives and gets hugs on the sidelines, like this one from Cal cheerleader Santia Andrews, who is now an alumna. (Photo courtesy of Oski Committee)

“It’s important to provide school spirit, to preserve the positive aspects of being a student on campus,” adds Milano, “including going to games, having rallies and keeping traditions like Oski alive.”

One of Milano’s favorite memories of Oski, she says, was a 2007 men’s basketball tournament in Los Angeles where “he had a dance-off with the (Stanford) tree and was so creative and lively and danced so well. That’s the best I’d ever seen him perform. It’s hard to do that in a bear suit.”

Rally Committee chair Keeton says Oski continues to be “an enigma that perfectly represents the university as a unique school.”

“I don’t know what Cal would be without Oski,” agrees Russell of the dance team. “He’s aged pretty well, and he continues to surprise and entertain me and to bring a smile to Cal fans of all ages. He’s got many years ahead of him, and is an integral part of the game day experience, mischievous and all.”