For undocumented students, Trump era brings fear and uncertainty

During his campaign, President Trump promised to repeal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, leaving students like Arturo Fernandez vulnerable

January 25, 2017

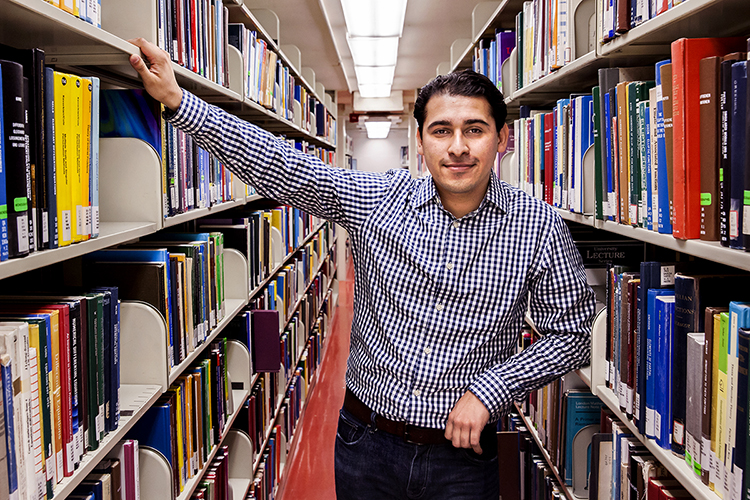

Growing up in the 1990s in Pittsburg, California, Arturo Fernandez felt like a typical kid.

He rode his bike around the neighborhood with friends, played on his church soccer team, watched the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers and played Pokémon on his Gameboy. He loved solving puzzles, and had an affinity for math.

He didn’t know he was undocumented. And, until recently, he didn’t much care.

Fernandez was born in Rio Grande, Zacatecas, Mexico, and moved to the U.S. with his family when he was just 3 months old.

In middle school, he participated in a program that mentored students in math at the local community college. To get college credit, he needed his Social Security number, so he went to his mom and asked her for it. That’s when she told him, “You don’t have one because you weren’t born here. You’re not a citizen.”

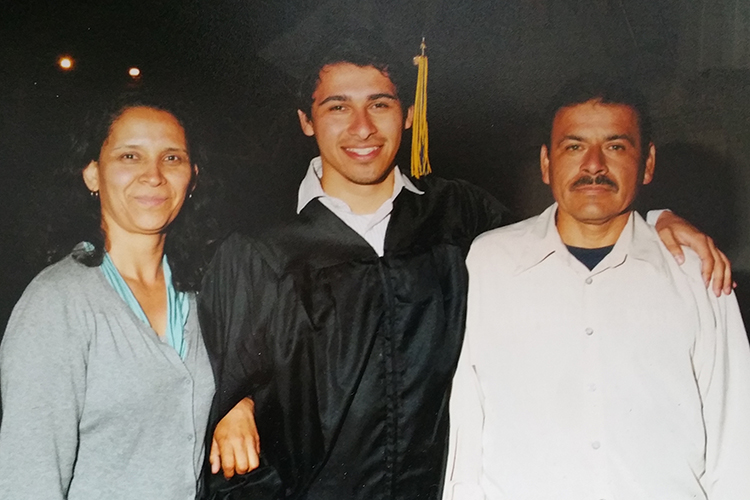

Fernandez, pictured here with his parents, graduated from UC Berkeley with a double major in applied mathematics and statistics and went on to pursue a Ph.D. in statistics. (Photo courtesy of Arturo Fernandez)

That was a surprise. But it wasn’t a major concern until the election of Donald Trump as president, which has alarmed Fernandez and other undocumented students across the nation.

During Trump’s campaign, as part of his platform for immigration reform, he promised to repeal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, an act that would threaten benefits for more than 700,000 young immigrants in the U.S.

DACA, a 2012 executive order by President Obama, allows children of undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. by their parents to receive temporary protection from deportation, work permits and a path to citizenship if they haven’t committed any crimes.

Students would face special hardships, says Meng So, who directs the Undocumented Student Program at Berkeley. Without DACA, he says, students would also lose work-study, leaving big holes in their financial aid packages. For graduate students like Fernandez, it would strip them of their tuition and fee remissions for their graduate research.

So also points to students’ heightened fears about what the government will do with the personal information they were required to provide when they applied for DACA.

Standing with students

As a high school student, Fernandez had one clear goal: Go to college. Working with a teacher and school counselor who helped him with college applications and finding scholarships open to undocumented students, Fernandez applied to 20 schools in California and was accepted to nearly all of them. He decided on UC Berkeley — the best decision he’s made, he says — and started in fall 2008.

But life as an undocumented college student turned out to be tougher than he thought. His classes were rigorous and demanding, and he was under immense financial strain. He was paying in-state tuition, thanks to a state law passed in 2001, and he’d received several private scholarships, but UC raised tuition at the end of his first year and suddenly the scholarships weren’t enough. (At the time, college students couldn’t apply for financial aid through the state, as they now can under the 2011 California Dream Act.) The 18-year-old wondered if he’d taken on too much.

“It was really hard,” he says. “Like a lot of students at Berkeley, I was trying to find my footing. Then, on top of that, I kind of had an identity crisis of what it meant to be undocumented. I’d lived in California my whole life, but I wasn’t a citizen. I grew up thinking, ‘I am America’s child.’ But then you get to an age where you can’t be.”

Struggling with his identity, unsure how he fit into his community, he knew he had to finish what he set out to do. He recommitted himself to a subject he’d been enamored of since he was a kid. “I fell in love with statistics,” he says.

In 2012, Fernandez was set to graduate from Berkeley with a double major in applied mathematics and statistics. But as an undocumented student, he wasn’t legally allowed to work, and pursuing a career in his field seemed like a far-off dream. “It was hard not knowing what my future would look like,” he says.

Two months before commencement, however, a new path emerged. He had received a reprieve: He had been approved for DACA.

For Fernandez, it meant he could continue his education in statistics by funding his Ph.D. research working as a graduate student instructor on campus.

“With DACA, I was hungry,” he says. “I was hungry to develop myself professionally and learn as much as I could.”

But he couldn’t do it alone. He needed the help of Berkeley’s Undocumented Student Program, which provides services to the 470 undocumented students on campus, from academic counseling to mental health support to legal advice. So, the program’s director, worked with Fernandez to find resources and apply to Berkeley’s competitive Ph.D. statistics program. Along with a cohort of eight others, he was accepted and began the following fall.

Fernandez flourished as a Ph.D. student. In addition to a job as a graduate student instructor, he worked with the program’s legal team to apply to travel abroad to conferences and attend research summer schools, expanding his professional network and scope of research.

He also a got a driver’s license — something he’d wanted for a long time, but was ineligible for — which added a layer of ease to his life he had never known.

Fernandez could feel himself returning to the kid he’d been in high school — proud of who he was and outspoken about his undocumented status. “Berkeley grad school has slowly given me that voice back,” he says. Now he worries the Trump White House will try to silence him and millions of other non-citizens.

While it remains unclear what changes the new administration will make, the Undocumented Student Program’s legal team says in a post-election FAQ that it’s highly likely DACA will be quickly rescinded.

In November, UC President Janet Napolitano said in a statement that UC’s 10 campuses will “protect the privacy and civil rights of undocumented students and will continue to welcome and support students, regardless of their immigration status.”

And the Undocumented Student Program promises to do what it takes to support these students. “We’re going to stand with our students,” says So. “We’re going to fight with them. We’re going to prioritize the highest degree of safety and security for them and their families.”

“Losing DACA would be like going backwards in time,” says Fernandez. “Instead of moving forward, like you thought you’d be — establishing your life, settling down, moving forward — now it feels like a lot of that is being taken away from you.”

So, however, says his program’s commitment to students and their families remains steadfast, and promises to do what it takes to support them.

“We must prioritize courage over comfort” he says, “and keep moving forward in a direction of growth and compassion.”

Learn more about the Undocumented Student Program.