From a border wall to a cultural bridge

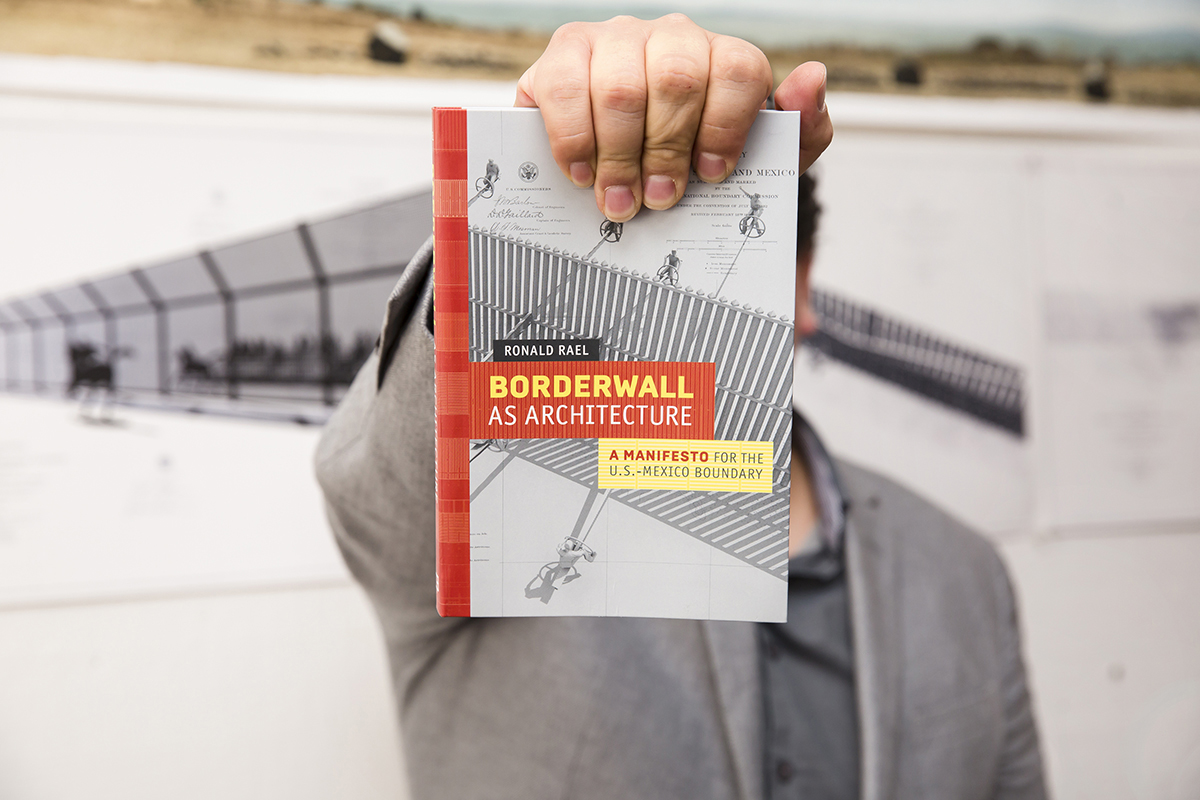

Architecture professor Ronald Rael reimagines the U.S.-Mexico border wall as a place to convene in his new book, Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary

April 5, 2017

Imagine a border wall between the U.S. and Mexico not as a barrier, but as a piece of architecture that brings people together. That’s what architect Ronald Rael does in his new book, Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary.

“The wall suggests a kind of duality,” says Rael. “That there’s one side or another. But I think it’s reductive to think about the borderlands in that way. It’s much more of a gradient than it is two sides.”

Rael is an associate professor of architecture in the College of Environmental Design at UC Berkeley. First, he wants to make clear that he doesn’t endorse building more of the border wall. Already, more than 700 miles of fence, steel and cement run along sections of about one-third of the border. Rather, he wants to rework what’s already there.

Ronald Rael is an associate professor of architecture at UC Berkeley. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

“In many ways we have to recognize that it’s a scar,” says Rael. “And we have to deal with the scar. Not cosmetically, but emotionally, physically. Architects have to insert themselves into the conversation.”

He envisions the border wall as a place to convene — to share books through the slats in the wall, use the wall as a volleyball net or go for a bike ride on a path alongside it. He even proposes installing a confessional for people to use right after they cross the border.

“It speaks to the irony of moving a few feet and becoming a sinner, and the necessity to just confess that sin,” he says.

A lot of Rael’s ideas build upon events that have taken place along the U.S-Mexico border in the past several decades — a famous 1957 horse race, for instance, or the artist who played the wall like a xylophone in 2014 — and worked to unite people from both sides.

Rael created models that show the different ways the border wall could be used to bring people together, not keep them apart. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Undeterred by the new administration in Washington, Rael remains committed to his vision. He says President Trump’s promise to build a wall as part of his plan for immigration reform isn’t anything new, and would only serve to alienate our neighbors in Mexico.

“It wouldn’t do anything to reform immigration issues in the U.S,” he says,” except maybe damage them.”

Also, he notes, net migration from Mexico has been negative or close to zero for years. The Pew Research Center estimates that 140,000 more Mexicans returned home than entered the U.S. from 2009 to 2014.

Further, Rael says that building a wall to keep determined people out of any place is simply ineffective. If they want in, they’ll manage cross the border no matter how tall, wide or strong the wall is.

“There will always be a way,” he says.

In 2014, Arizona artist Glenn Weyant, a self-described “border deconstructionist,” played the border wall like a xylophone. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

The day after the 2016 presidential election, Rael wrote the last paragraph of Borderwall. “While Trump has not yet built his ‘great wall’ literally,” he wrote, “he certainly has done so figuratively, both in the borderlands… and within our own body politic.”

But, Rael says, building more walls to divide communities from one another is not the answer.

“What’s most important is to begin to dismantle the walls that divide us,” he says. “Not only physically, but the conceptual walls that divide us in terms of religion or sexual identity or race or culture.”

Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary, published by University of California Press, is on sale now. New York’s Museum of Modern Art has an exhibit featuring drawings from the book as part of its permanent collection.