Campus, city to mark WWII internment of Japanese Americans, 75 years on

Seventy-five years ago, during WW II, 1,300 people of Japanese ancestry in Berkeley were rounded up and moved into prisons called internment camps

Eleanor Breed

April 24, 2017

Seventy-five years ago at UC Berkeley, final exams were approaching and graduation was in sight. But spring semester 1942, during World War II, wasn’t to end in a typical way.

Public opinion had turned against Japanese Americans following the Dec. 7, 1941, attack by Japan on Pearl Harbor. And on April 24, 1942, under U.S. Presidential Executive Order 9066, “all persons of Japanese ancestry” in Berkeley were given one week to prepare for their forced removal to an internment camp. The deadline was May 1 at noon.

Baggage belonging to Japanese Americans in Berkeley piled up curbside next to a bus bound for Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno. (Photo by Eleanor Breed)

Each of Berkeley’s approximately 1,300 residents of Japanese ancestry would be assigned a number by the military and taken by bus to an overcrowded assembly center at the Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno. There they would be housed for months among some 8,000 people in horse stable stalls, on grandstands or in quickly built barracks, often made of tar paper, in the infield.

Eventually, 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast were transferred to 10 internment camps in remote areas of six western states and in Arkansas. Confined by armed soldiers, they included UC Berkeley faculty, staff and about 500 students whose educations came to an abrupt halt.

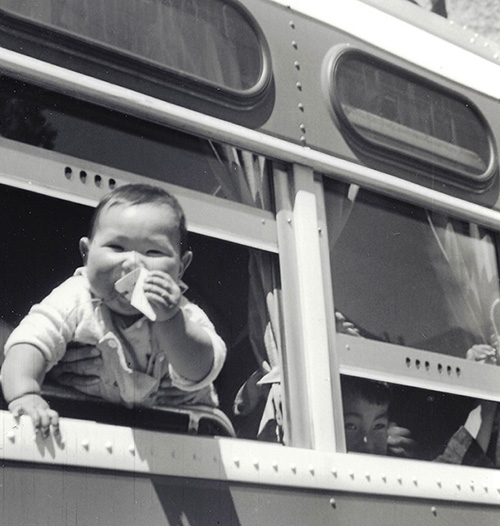

A baby tugs on its ID tag from the window of a bus transporting Japanese Americans to Tanforan. (Photo by Eleanor Breed)

This week, on Wednesday, April 26, President Franklin Roosevelt’s executive order and its effect on Berkeley will be remembered both on campus and in the city with a free public reception, an exhibit, a talk by a Berkeley alumnus incarcerated at age 9 and a public ceremony at First Congregational Church of Berkeley. The church boldly supported those ordered to surrender their freedom, homes, jobs and possessions. A permanent plaque recalling the events of April 1942 will be presented at the church commemoration.

At the campus exhibit, Keith Nomura, whose father was taken to Tanforan as a UC Berkeley senior, will display his father’s diploma and the mailing tube it arrived in at the racetrack barracks. He also plans to share at the church the story of Kiyosuke Nomura, who died at age 80.

“I feel it’s my calling to continue telling the story of my dad and his family, so that people see the human side,” Nomura says. “When you put a personal voice to this horrible thing that happened, it’s hard for people to ignore it.”

“The mass imprisonment of the Japanese American population inflicted trauma on the victims that lasted a lifetime and affected their descendants,” says Milton Fujii, a former UC Berkeley staff member who is organizing the April 26 events with Berkeley community historian Steve Finacom. “It’s important that all Americans today understand what happened so that we can all move forward.”

Standing up to injustice

While the story of these Japanese Americans is familiar to many, what isn’t as commonly known is how the campus community and many Berkeley residents took a stand against Roosevelt’s Feb. 19, 1942, executive order. An ethnic history project conducted by T. Robert Yamada for the Berkeley Historical Society and published in 1995, found that:

-

Robert Gordon Sproul, UC president from 1930 to 1958, petitioned dozens of universities and colleges in inland states to admit Berkeley’s Japanese American students so their educations wouldn’t be interrupted. (UC Berkeley photo)

UC President Robert Gordon Sproul wrote to more than 30 Midwestern schools in hopes of finding spots for UC Berkeley’s Japanese American students, so they could continue their studies. Semester grades were given to them based on midterms.

- A student relocation council was formed at Stiles Hall and became a model that eventually led to the creation of the National Japanese Student Relocation Council, which helped thousands of Japanese Americans continue with college.

- Leading Berkeleyans organized the Committee on Fair Play to speak out against anti-Japanese hysteria and advocate for the release of Japanese Americans and their re-integration into the community. Sproul, Provost Monroe Deutsch and former UC President David Prescott Barrows, then a political science professor, were members, as was Berkeley economist Paul Taylor. Taylor’s wife, photographer Dorothea Lange, vividly chronicled the removal of Japanese Americans and their lives in the camps for the War Relocation Authority; many of the images were impounded and kept from view for more than 50 years.

- Berkeley faculty and researchers conducted the University of California Evacuation and Resettlement Study. Housed today in the Bancroft Library, it is considered a critical collection of materials on the evacuation and resettlement of Japanese Americans.

-

A plaque with this wording is being placed in the First Congregational Church of Berkeley on Wednesday during a ceremony of remembrance.

The First Congregational Church of Berkeley convinced the Army to let the church serve as the registration and departure center for Berkeley’s evacuees, who originally were to report to a vacant auto dealership parking lot on Shattuck Avenue. Members of various Berkeley faith groups showed up daily to serve food, to help their Japanese American neighbors find places to store their possessions and to locate homes for their pets.

- Delegations of Berkeley students and city residents visited Berkeley’s Japanese Americans in the camps. Stiles Hall and International House sent books and other supplies to Utah’s Topaz Relocation Center, when detainees were transferred there.

- The ASUC passed a resolution stating on behalf of the student body, “The University of California reasserts its belief in the principle of judging the individual by his merit and its opposition to the doctrine of racism. It extends to relocated students planning to attend this university its assurance of welcome admission to membership in our student body.”

When the ban was lifted, according to Yamada’s report, the Berkeley Interracial Committee conducted a job and housing survey, passing out 4,000 questionnaires to help returnees find housing and jobs. Temporary hostels were organized for those leaving the camps, and students with cars met the returnees as they arrived in Berkeley by train.

Telling their stories

But despite these humane efforts, says Finacom,“we shouldn’t fully sugar-coat the history. Berkeley was racially segregated in housing and employment when World War II started, and there was some local condemnation and harassment of Japanese Americans who had made the community their home. Many who later returned to Berkeley had lost homes, possessions, businesses and livelihoods and never recovered.”

A September 1944 photo of UC Berkeley art professor Chuira Obata. On the faculty from 1932 to 1954, he was sent to the Tanforan detention center. Obata and his wife were forced to close their art supply store on Telegraph Avenue after it was shot at following the attack on Pearl Harbor. (National Archives and Records Administration photo by Hikaru Iwasaki)

Yoshiko Uchida was studying for finals at Berkeley when her family had to sell much of its furniture and to ask friends and neighbors to keep its prized possessions, including eight large boxes of books, a piano, flowering plants and a two-year-old Buick sedan. Uchida, who wrote about her experience in a 1966 California Monthly article, had to put an ad in the Daily Cal to find a new home for her pedigreed Scotch collie, who died after the family moved away.

“It is a terrible thing to be afraid, not because of something one has done but because of one’s appearance,” she wrote. “Many of the Chinese students at the university sought protection by wearing small badges reading, ‘I am Chinese’…Most of us had never been to Japan. What could we do, we wondered, to make people understand that we had but one loyalty – to the United States?”

“I don’t know if most people realize or not, but merely food, shelter and clothing is not enough for life,” Hayao Abe, a former resident of International House, wrote in an Aug. 5, 1942, letter from the Santa Anita racetrack near Los Angeles, where her family was imprisoned, to Eleanor Breed, secretary at the First Congregational Church of Berkeley. “And after living in an environment and atmosphere full of liberties, privileges, space,…it’s a shock… Your faith in the American way of life wavers.”

Nomura says his father, who in 1942 “was abruptly taken from his trajectory; he was on an upward arc as a student,” didn’t really start to heal from the ordeal that he and his Berkeley mother and two younger siblings endured until the campus honored, at fall convocation in 1992, the Japanese Americans whose education had been cut short 50 years earlier. “In his 70s, he finally felt recognized, there was closure for him, that’s my hunch,” said Nomura, “He said he felt that he wasn’t ashamed and started tell me the stories, the good stories and the bad stories.”

Rev. Vere Loper (at left), then-minister of First Congregational Church of Berkeley, kept a journal of the events that unfolded. (Photo by Eleanor Breed)

At a Dec. 13, 2009, special campus event, 42 former students – in their 80s and 90s – received degrees they should have gotten 70 years prior. Many using canes, they climbed the stage in Haas Pavilion wearing caps, gowns and leis of blue and gold origami cranes that were constructed by local school children. Family members accepted the honorary degrees for 78 additional Japanese Americans no longer alive or too ill to attend.

In the place of her grandfather, Seiji Kiya, who died in 1997, 10-year-old Elise Kiya accepted an honorary degree at a similar May 20, 2010, campus ceremony for 11 Japanese Americans. Seven of the degrees were awarded posthumously.

This Wednesday’s commemorative exhibit, reception, program and commemoration “are timely and sobering,” says Finacom. “As the United States deals with continued xenophobia and prejudice, we remember that it did happen here 75 years ago, and could happen again.”

The events are being sponsored by First Congregational Church of Berkeley, the Berkeley Historical Society, the Japanese American Citizens League’s local chapter and a number of campus organizations.