Hubert Dreyfus, preeminent philosopher and AI critic, dies at 87

A scholar of Heidegger who taught generations of independent thinkers

April 24, 2017

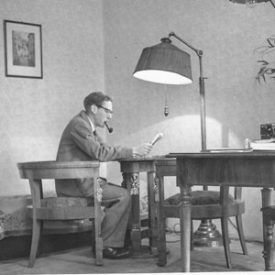

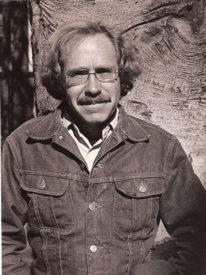

Hubert Dreyfus (1929-2017) Photos courtesy of Genevieve Boissier-Dreyfus

Hubert Lederer Dreyfus, a preeminent scholar of 20th-century European philosophy, early skeptic of artificial intelligence, iTunes podcast star and UC Berkeley professor emeritus of philosophy, died at his home in Berkeley on Saturday, April 22, from cancer. He was 87.

A prolific Harvard-educated philosopher, Dreyfus taught at UC Berkeley for nearly 50 years, explaining to generations of students the philosophies of such iconic thinkers as Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Soren Kierkegaard.

While Dreyfus — known to his family and friends as Bert — retired in 1994, he remained active as a professor in the Graduate School, teaching philosophy until his last day of class on Dec. 3, 2016.

“Reports of my demise are not exaggerated,” was the line posted on Dreyfus’s Twitter feed shortly after his death, spurring widespread sadness and reflection upon his legacy.

A campus memorial for Dreyfus will be held May 24 at Alumni House from 1:30 to 3:30 p.m.

“Bert Dreyfus will long be remembered by his colleagues for his groundbreaking work on Heidegger, his extraordinary teaching and mentoring and his unswerving commitment to the welfare of our undergraduates,” said Hannah Ginsborg, a professor of philosophy at UC Berkeley and the department’s chair.

“We’re happy that he was able to carry on with all aspects of his work right up to the end, and the intellectual openness and sense of excitement which pervaded his teaching will continue to serve as an inspiration for us,” she added.

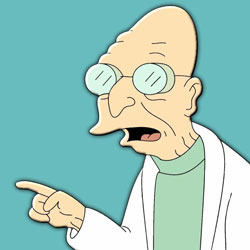

Futurama’s Professor Hubert Farnsworth was named after Dreyfus.

Dreyfus’s proteges include philosophers Taylor Carman, John Haugeland, Iain Thomson, Mark Wrathall, Sean Kelly and Eric Kaplan, a writer and producer on such comedy TV series as The Big Bang Theory, The Simpsons and Futurama, who named the quirky Futurama character “Professor Hubert Farnsworth” after Dreyfus.

“Bert was a completely genuine, honest intellectual and philosopher who cared about thinking, even if it made him seem strange,” said Kaplan, who studied under Dreyfus in the 1990s and plans to complete his Ph.D. in philosophy at Berkeley this year. “He was an inspiration in terms of an original thinker and mentor, and a lovable teacher. He was a gigantic influence on me as a human being and as a student of philosophy.”

Alva Noë, a UC Berkeley philosophy professor and close friend of Dreyfus, said that though his death was not unexpected due to his terminal illness, it is nonetheless “a devastating loss.”

“Dreyfus was one of philosophy’s greatest and most influential teachers,” Noë said. “We owe him so much, for his reading of Heidegger and existential phenomenology, as well as his criticism of (Edmund) Husserl, his investigation of the limits of artificial intelligence and his exploration of the phenomenology and psychology of skill and skillful coping.”

Dreyfus’s acclaimed writings include the New York Times bestseller All Things Shining (2011) which he wrote with Harvard philosopher Sean D. Kelly; three editions of What Computers Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason (1972, 1979 and 1992); Being-in-the-World (1991) and the 2001 essay series On the Internet. His work on Heidegger inspired the 2010 documentary Being in the World.

As far back as the 1960s, he challenged expectations for artificial intelligence, arguing that machines lacked the intuition to compete with human intelligence.

“He didn’t think the highest human capacities were rule-driven, that we go through a series of steps like an algorithm,” Kaplan said.

That said, Dreyfus never shied away from technology. His podcast lecture “From Gods to God and Back” ranked among the most popular webcasts on iTunes in 2007, with a worldwide cult following that included a Texas long-haul trucker and an Alaska fisherman.

Perhaps his greatest legacy is the mark he made on the hundreds of students that took his classes and were inspired to major in philosophy, which was among the fastest-growing majors at UC Berkeley in 2011.

“Dreyfus’s influence will live on in the dozens of Ph.D. students he supervised and mentored, who are now spread out across the globe,” wrote Kelly in an online eulogy. “I am grateful to count myself among their number.”

Hubert Dreyfus was born on Oct. 15, 1929, in Terre Haute, Indiana, to Stanley Dreyfus, a businessman in the poultry industry, and Irene Lederer Dreyfus, a homemaker. He was the older of two sons.

“He said he learned that he wasn’t the center of the universe when he was a little kid, and his parents visited a younger brother on him,” Kaplan said.

Dreyfus attended Wiley High School in Terre Haute, where his success on the debate team paved his way to Harvard University. He majored in physics before switching to philosophy after hearing a lecture by American philosopher C.I. Lewis.

His circle of friends at Harvard included poet Adrienne Rich, religion scholar Huston Smith and playwright A.R. Gurney. His long friendship with Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor dated back to 1951.

After earning a bachelor’s degree, master’s degree and Ph.D. in philosophy at Harvard from 1951 to 1964, he taught at Brandeis University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he was introduced to the field of artificial intelligence. The idea of thinking machines captured his imagination, and fueled his skepticism, for decades to come.

In 1968, he joined the faculty of UC Berkeley as an associate professor of philosophy. That same year, he won the Harbison Prize for Outstanding Teaching.

Throughout his five decades at Berkeley, he received visiting professor appointments that took him around the world. While in Germany, he bought a green convertible 1970 Volkswagen Karmann Ghia, which was his pride and joy.

Throughout his five decades at Berkeley, he received visiting professor appointments that took him around the world. While in Germany, he bought a green convertible 1970 Volkswagen Karmann Ghia, which was his pride and joy.

“Strangers frequently approached him to share their stories of Ghias in their lives, or left him notes on the windshield,” said his wife of 42 years, Geneviève Boissier-Dreyfus. “Some even took pictures of themselves by the Ghia with the Campanile in the background.”

The two met in 1971 through mutual friends in Paris. She joined him in Berkeley in 1974, and they had a son and daughter, Stéphane and Gabrielle.

A decade later, he wrote the book Mind over Machine with his brother Stuart Dreyfus, who is currently a professor emeritus of industrial engineering at UC Berkeley.

As a teacher in the 1990s, his humility was said to be boundless: “He was never about trying to shove ideas down your throat. It was never about the greater glory of Bert Dreyfus,” Kaplan said.

Among copious other accolades, Dreyfus was a 2001 fellow at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. At UC Berkeley, he won the Rhoda H. Goldman Award for Distinguished Faculty Advising of Undergraduates in 2003, and a Distinguished Teaching Award in 2004.

He was also the recipient of an honorary doctorate for “his brilliant and highly influential work in the field of artificial intelligence” and interpretation of 20th-century philosophy from Erasmus University in the Netherlands.

“Dreyfus’s influence at the end of his life is greater than ever, and will remain a vital force, not only in philosophy, but also in the cognitive and human sciences more broadly,” Noë said.

He is survived by his wife, Geneviève Boissier-Dreyfus, of Berkeley; son Stéphane Dreyfus and daughter-in-law Jessica Kung Dreyfus, of San Francisco; daughter Gabrielle Dreyfus and son-in-law Benjamin Phillips, of Washington, D.C.; and brother Stuart Dreyfus, of Berkeley.