New course to tap UC Berkeley’s diversity and maker spirit

HHMI sponsors bioinspired innovation course to help students design their own future

December 13, 2017

Robert Full wants to tap the diverse experiences of UC Berkeley undergraduates to teach them the fun of discovering biology’s secrets and the innovations that can spring from hacking them.

Maybe he’ll spark a few entrepreneurs in the process.

Thanks to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, he now has $1 million to realize that dream and show students how biology can help them design their future and give back to their communities.

Robert Full (right) showing students the adhesive pads of a gecko, an inspiration for an entirely new field of research and new products, including bandages that stick when wet.

Full, a professor of integrative biology, is one of 14 HHMI Professors at nine institutions announced today by the Maryland-based organization, the largest private funder of biological research in the United States. The professorships come with a five-year grant allowing the scientists to develop innovative classes that will serve as models for teachers at other universities as they attempt to engage students of all backgrounds.

Full’s goal is to introduce students to curiosity-based, fundamental research by focusing on the biological discoveries made by plants and animals – ranging from sticky spider silk to the complex mechanics of running on four, six or eight legs – and motivate them to design products for humans based on these discoveries, but better. While undergrads fulfill their biology breadth requirement, they will begin to see possible next steps, explore future careers and even test ideas for startups.

“The core of the course is scientific discovery, but I also want students to understand that you never know where curiosity-based research will lead and that fundamental discovery creates principles and facts that we can use to design the future,” Full said.

Full has spent his entire career doing just that. He has analyzed the movements of cockroaches and applied those principles to build robust search-and-rescue robots that can go almost anywhere. He discovered the secret of how gecko toe hairs stick and launched a new industry of fibrillar adhesion. His discoveries about how crabs maneuver in the surf have led to underwater mine-detecting robots. He directs the Poly-PEDAL Laboratory, the Center for interdisciplinary Bio-inspiration in Education and Research (CiBER) and is the editor-in-chief of the journal Bioinspiration & Biomimetics.

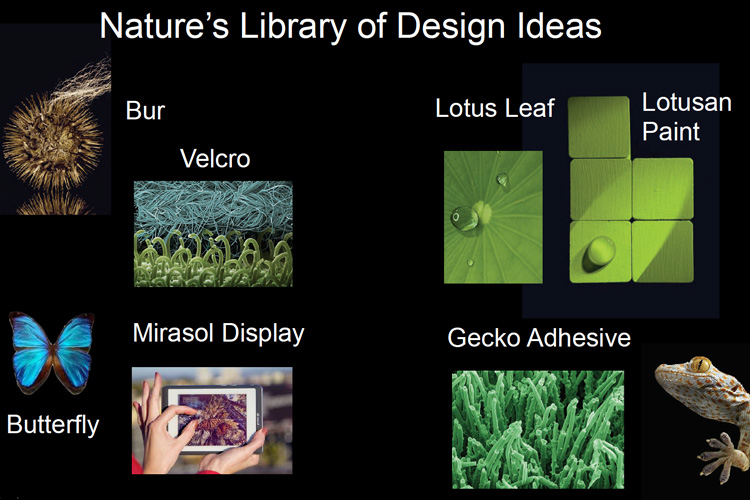

Examples of four biological innovations that have inspired products already or soon to be on the market. (Courtesy of National Geographic)

The key, he found, is not to copy nature, but to improve on nature’s design principles.

“One thing I teach my students is that organisms are not optimal. When you look at an organism, it had to grow, but your design doesn’t have to grow,” he said. “We extract the design principles and leave the evolutionary constraints behind.”

Combining the study of biology with making things has become easier thanks to the proliferation of maker spaces on campus, such as UC Berkeley’s Jacobs Institute for Design Innovation, where Full teaches his course. Equipped with laser cutters, electronics labs, 3D printers and a plethora of other tools, such spaces make it easy for students to build prototypes to test their designs.

In a Discovery Course he first taught last spring in the College of Letters & Science, Full had his 180 students study gecko toe hairs, which allow the animal to stick to walls and ceilings, and come up with possible uses for artificial adhesives they actually make in lab. Students also assemble a legged robot and are tasked to redesign the robot for societal benefit. The robot, named DASH, is from a robot-making kit designed by former UC Berkeley graduate students to mimic cockroaches and now being sold by Mattel.

As the students explored nature’s designs and thought about ways to improve on them, they learned how to extract key biological principles and design new biological experiments, which are at the heart of scientific discovery, Full said.

“The goal is not delivering content. It is to prepare them for the fact that, in many cases, the jobs that they will hold haven’t even been created yet,” Full said. “It’s predicted that they will change jobs three to five times in their career, which is very different from the last century. So we need to equip them with specific skills, such as critical thinking and problem solving, collaboration and interdisciplinary thinking.”

Full with one of his favorite subjects, a Tokay gecko.

Assembling diverse and inclusive student teams will be a key part of the course, since studies have shown that homogeneous teams can be mediocre incubators of innovation. Diversity of background and perspective provides a better source of new ideas, he said. To encourage broad participation, Full will partner with UC Berkeley’s successful Biology Scholars Program.

“You want to make sure teams have tapped into the unique voices of every team member and heard what they can offer, which requires some training – it doesn’t just happen,” Full said. “Diverse minds and diverse ideas are what provide innovation. That inclusive excellence, which is the theme of the grant, is essential for the next generation of discoveries and inventions.”

This is the 14th year of the HHMI Professorships, which have been awarded to 69 people, including this year’s class. UC Berkeley geneticist Jasper Rine received a five-year grant in 2006 to develop a class that introduced undergraduates to the modern world of experimental biology.

RELATED INFORMATION

- HHMI announcement

- Robert Full’s Poly-PEDAL Laboratory