For Native American student, reclaiming his culture began at Berkeley

As a freshman, Sean Brown found a trove of rare recordings of his ancestors in the California Language Archive, recorded 100 years ago on wax cylinders and digitized by an innovative technique called Project IRENE

June 5, 2018

Growing up on his reservation, Sean Brown never heard his native language spoken. From the Paiute Tribe in Bishop, California, Brown was born a week after his grandmother died. She was the one, he says, who held the family together and kept their traditions alive, so when she was gone, the family’s connection to its culture and each other grew weak.

Sean Brown, a UC Berkeley sophomore this fall, is from the Bishop Paiute Tribe in Bishop, California. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Now, Brown, who just spent his freshman year at UC Berkeley, is on a quest to discover who he is and where he comes from. And to bring his family closer together.

“It’s up to the young generation to take on that role,” he said. “We have to go talk to the elders, learn from them. Learn everything we can from the people who still know. I want our family to be together, how we used to be.”

When he started at Berkeley last fall, Brown looked for ways to connect to the native community on campus.

He enrolled in a linguistics class, where he started to learn his native language, Nüümu. He joined the Native American Theme Program, a campus group that supports indigenous students in becoming leaders. The group volunteered at UC Berkeley’s 39th annual pow wow in April. (See the photos below.)

And Brown began to pore over campus archives — audio recordings, photos, journals — to find firsthand accounts of what life was like for his tribe throughout history.

In his research, he came across a series of audio recordings in the California Language Archive of his great-uncle Roy Chiatovich, who died in 1970, singing traditional songs. “You can hear him singing hand game songs,” said Brown. “He had a really great voice.”

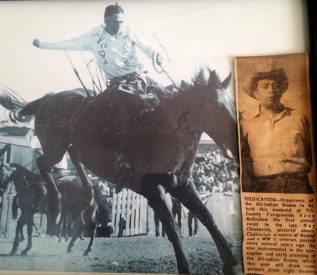

Roy Chiatovich (pictured), Brown’s great-uncle, can be heard in recordings that Brown found in the California Language Archive. (Photo courtesy of Sean Brown)

The recordings come from a Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology collection made between 1900 and 1940 by UC Berkeley anthropologists, led by professor Alfred Kroeber, as part of an effort to document and preserve the native cultures and languages of California. Recorded with phonographs on some 3,000 Edison wax cylinders were the voices of Native Californians from dozens of regions and cultures speaking and singing, reciting histories, narratives and prayers and listing names for places and objects, in nearly 80 languages.

It’s remarkable that Brown was able to hear these recordings because over time, the fragile wax cylinders had degraded — some had even broken into pieces — and playing them would have damaged, and possibly destroyed, them. The recordings would have been lost forever.

But the audio has been transferred from the wax cylinders to a digital archive over the last few years.

Brown reads transcriptions of handwritten manuscripts of Paiute oral histories from the Paiute and Shoshone Historic Manuscript Transcription Project, part of The Ethnological Documents of the Department and Museum of Anthropology collection at the Bancroft Library. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

How? Beginning in 2002, researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory — Earl Cornell, Vitaliy Fadeyev and Carl Haber, working with the Library of Congress — created a way to digitize the sound, bringing back to life languages, some of which have been transformed, fallen out of use or are no longer spoken.

The digitization method is called Project IRENE. It uses a non-contact optical scanner, nicknamed “IRENE,” to scan the cylinders. The scanned images are imported into a program called Weaver, created by Cornell, which analyzes the data and turns them into sound. (The names IRENE and Weaver come from the first record the team was able to reproduce with the system — a single of “Goodnight Irene” by the Weavers.) There are only six IRENEs in the world and two are in Berkeley — one on campus and one at the Berkeley Lab.

After the wax cylinders are digitized — they have scanned some 2,800 so far — they are catalogued, then sent to the linguistics department, where a team reviews the recordings and then uploads them to the California Language Archive, a digital catalogue that includes more than 16,000 audio files of 425 languages for the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages.

Julia Nee, a Ph.D. student in the linguistics program, has reviewed hundreds of recordings since she began working on Project IRENE last year.

Julia Nee, a Ph.D. student in linguistics, works in language documentation and revitalization. She has been working on Project IRENE for the past year and helped Brown access recordings of his family on the California Language Archive. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

“Now that about 1,500 of these recordings are on the archive,” said Nee, “I’ve been getting a lot of requests from tribal members from a lot of these different groups to hear the audio. It’s been a really rewarding process.”

Although the audio is catalogued on the archive, most of it isn’t for public use, says Nee. But tribal members and researchers can request access by explaining their purpose.

“There are some traditional songs and dances that are only meant to be performed or listened to at particular times of year or by particular people,” she said. “There might be songs that are specific for women or men. Or for winter or summer or raining season or dry season. And if the wrong people listen to them at the wrong time, it’s believed to have negative effects on the community.”

After Brown requested the recordings of his great-uncle Roy singing, he burned a CD and took them to play for Roy’s son, Wayne, now in his 70s. Although Brown grew up on the same reservation as Wayne, he had never really spent any time with him.

“Listening to the songs, Wayne started singing along,” said Brown. “He knew all of them. His dad passed that down to him. He sounds like his dad, and my dad says he looks just like his dad. It was emotional, but it was good because we were together.”

Although the recordings of Brown’s family aren’t available to the public, there are a handful of recordings on the California Language Archive, including narratives in Salinan recorded in 1910 about a trip to San Francisco and another about fighting forest fires, as well as a 1902 recording in Rumsen called “Myth of Coyote.” The recordings are scratchy, and can include clicking, thudding and distortion caused by decay or debris, such as dust and scratches, on the surface of the cylinders. Researchers apply filters to the recordings to reduce the noise, analyzing each cylinder on a microscopic scale to make sure they never remove any of the original audio.

- Listen to “Myth of Coyote” in Rumsen, 1902.

- Listen to “Fighting Forest Fires,” a narrative in Salinan, 1910.

- Listen to “My Trip To San Francisco,” a narrative in Salinan, 1910.

- Listen to “Spanish-Salinan brief vocabulary I,” numbers 1 – 10, 1910.

- Listen to “Spanish-Salinan brief vocabulary II,” 1910.

This summer, Brown is back home in Bishop working to deepen his connection to the community. He’s participating in a language program in the cultural center, building traditional homes with tribal members and learning Nüümu.

Brown says it’s his goal to teach young native people about where they’re from and who they are.

“To know these stories, to know these songs, to know our ways is important,” he said. “Because once we stop passing along that knowledge, we’re going to stop knowing who we are as a people. And we won’t be a tribe anymore.”

Brown says it’s his goal to teach young people about who they are and where they’re from. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

This week — June 3-9 — the campus, with the Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival, is hosting the Breath of Life Institute, a weeklong conference where Native Californians can explore and use the archives of the California Indian languages and materials for their own efforts in language reclamation. Now in its 12th year, the conference offers lectures and workshops on linguistics to help participants learn how to understand the written materials and bring them back into spoken language.

Learn more about the Native American community at UC Berkeley.