Concert will mark 100th anniversary of end of World War I

More than 2,000 from UC Berkeley's community fought in the Great War, which transformed the campus

November 8, 2018

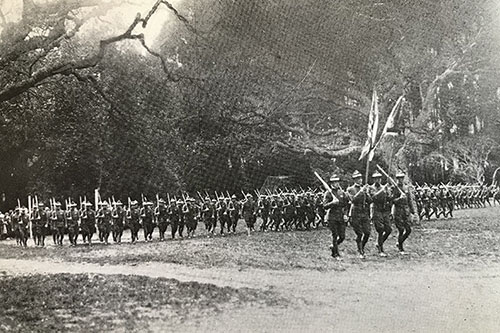

A banner bearing 2,200, the number of campus community members who served in World War I, was unfurled from the Campanile’s west face — facing the Golden Gate Bridge — on March 22, 1918. That day, Gov. William Stephens was in Berkeley reviewing the campus regiment. (California Monthly photo)

If you hear the Campanile bells playing “God Save the Queen” this Sunday, don’t look around for visiting royalty. England’s national anthem — along with “La Marseillaise” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” — will be part of a carillon concert marking the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I.

At 11 a.m. in Paris on Nov. 11, 1918, “the Armistice of 11 November 1918” was signed, ending the fighting on land, sea and air. The “Allies” included Britain, France, Italy, Russia and the United States. Their opponents were the “Central Powers,” including Germany, the Austrian-Hungarian and Ottoman empires and Bulgaria.

Sunday’s special concert — also on Nov. 11 at 11 a.m. — will repeat some of the tunes played 100 years ago when word of the armistice reached Berkeley from Washington. According to an article in the Nov. 11, 1918, Berkeley Gazette, the tower’s bells began ringing at 2 a.m., and “wild scenes of excitement” erupted in Berkeley.

It added that “…approximately 2,000 men and women hastily dressed and joined in a celebration which resounded throughout the city. The chimes in the campanile at the university heralded the victory…The factory whistles and sirens of West Berkeley joined in…Sleep was impossible.”

World War 1 era drawing in the 1918 Blue and Gold yearbook, UC Berkeley.

At a bonfire on the corner of Shattuck Avenue and Center Street, hundreds of people reportedly gathered to sing patriotic songs. City Hall proclaimed a holiday, several parades were held, and at noon at the university, students were released from their classes. A 4 p.m. “mass meeting” at the Greek Theatre focused on “the coming of peace.”

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, brought a permanent end to the war.

More than 2,200 members of the campus community actively served in the Great War, which claimed the lives of about 100 known individuals from Berkeley. At the same time as this Sunday’s 11 a.m. concert, Mayor Jesse Arreguin will unveil a refurbished plaque that honors the dead at the downtown Veterans Memorial Building, 1931 Center Street.

Berkeley as a WWI military training center

World War I broke out in Europe in July 1914. While the United States remained neutral until 1917, many Berkeley students enlisted in the volunteer ambulance corps and went overseas to support the allies in France and Belgium. Anti-German and pro-British sentiment emerged on campus and in the city.

During fall semester 1918, a Students’ Army Training Corps unit was established on campus for about 1,500 men. Areas on campus were cleared to build wooden barracks and a mess hall. (1920 Blue and Gold photo)

With American involvement looming in 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the National Defense Act, setting up the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC). Berkeley’s existing Cadet Corps evolved into the ROTC.

Once the United States entered the war in April 1917, many faculty and staff enlisted, or went on leave, to work for the military or other federal government departments. A large number of male students enlisted in the armed forces; others were drafted.

Patriotic rallies and events were held at the Greek Theatre, and the chemistry building, Gilman Hall, was used for classified research.

The U.S. School of Military Aeronautics was founded at Berkeley in 1917, and the “ground school” was considered one of the two best schools of its kind in the country. Many alums entered the aviation service, and several became instructors and officers. This photo shows the Fleet Flying Cadets’ color guard. (1919 Blue and Gold photo)

World War I lacked trained pilots, so a U.S. School of Military Aeronautics opened in 1917 on campus — one of only a handful nationwide. For an eight-week curriculum, the government provided military instructors, uniforms and a tuition fee of $40 for the first four weeks and $5 per week afterward. Students learned the theory of flight, meteorology, principles of radio, aerial photography and tactics. Flight training was done off campus. Berkeley’s peak enrollment at the school was 1,500, and some 2,000 pilots graduated before the program closed during the 1919-20 academic year.

Berkeley community historian Steve Finacom said that pacifists in Berkeley during World War I experienced some anti-German xenophobia and hostility.

He added that the city and the campus also “vigorously raised funds for war bonds and civilian relief in Europe, experienced shortages as resources went to support the war effort, grew Victory Gardens and saw a housing shortage as workers flocked to war industries in the East Bay.”

All of these patterns, said Finacom, would repeat locally a quarter of a century later during World War II.

Lasting tributes to members of the campus community who died in World War I are California Memorial Stadium and the bench with the stone “mourning” bears on it just outside the Campanile’s lobby door.

NOTE: This Sunday’s 11 a.m. concert will be played by Leslie Chan, a student of University Carillonist Jeff Davis. The carillon recital held every Sunday at 2 p.m. will be performed as usual. Some of the music played at 11 a.m. will be repeated at 2 p.m.

Also at the 2 p.m. concert, a work called “A Sacred Suite” will have its premiere at Berkeley and in more than 50 locations around the world. It was commissioned for this Sunday’s inauguration of the Peace Carillon in Leuven, Belgium, as a symbol of peace and reconciliation between the cities of Leuven and Neuss, Germany. German troops — most of them from Neuss — ravaged Leuven on Aug. 25, 1914, and Leuven’s city carillon in St. Peter’s Cathedral did not survive. The Peace Carillon is a joint project of the two cities.